6 The Risk Hermeneutic and Functional Analysis

Sociological theories have inspired the records continuum. For politically charged groups, challenging ideas about organisational culture would benefit from a critical appraisal approach, with a social and human-centered lens. Hermeneutics too is at the heart of the records continuum and theorising about the decision making of the individual in broader society and the impact of appraisal has (in the memorialising and forgetting of events and trace) is foundational to understanding community recordkeeping.

The records continuum is not just about record objects in space but about representing performances and relationships across an evolving recordkeeping ecosystem. Since continuum theory embodies structuration hermeneutics, what people are doing in their action and the recurrent social practices that inform those actions dictate the recordkeeping across the axes and dimensions of the Records Continuum Model. The hermeneutic circle (or spiral[1]) is about understating holism and context in societal relationships, communities and individual agency in a political arena. It represents “a process of interpretation in which we continually move between smaller and larger units of meaning in order to determine the meaning of both.”[2] Records are traces of experiences, but what led to these traces and what societal structures influenced the creation of the records is key to understanding appraisal – the how, when and why records are created or where they are not.

Structure and Agency into Action for Change

Activity and activism go hand in hand and radical recordkeeping is a trace of activity intertwined with political intent. These ideas draw from philosophies that align to understanding the systemic structures of recordkeeping in society. Structuration Theory explores the relationship between structure and agency, highlighting the multi-faceted nature of action in society. The challenge of balancing structure and agency echoes the age-old philosophical debate between free will and determinism. This dilemma questions how individuals can both be influenced by social structures but still make free choices and take actions.[3] Anthony Giddens’ structuration philosophy is particularly relevant here, as it introduces the duality of structure into this interplay between structure and agency. Structurationists, adhering to Giddens’ framework, argue that while social structures certainly shape and condition our actions, they don’t outright determine them. Instead, they assert that individuals retain a degree of autonomy, capable of making decisions within the parameters set by these structures.

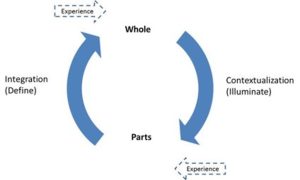

Fig. 6.1 Dimensions of the Hermeneutic Circle. [4]

In Figure 6.1, Ronald Bontekoe visualises the hermeneutics in decision making and sense-making through the contextualisation and integration into the parts of experience then influencing the whole of action. The above diagram shows that knowledge begets knowledge, each new piece adding depth to our understanding. Fresh information nourishes our insights, fostering their evolution. This process mirrors the gradual unfolding of human perception, where revelations emerge piece by piece, requiring synthesis to illuminate what we seek to comprehend. This not only parallels philosophical inquiries into social structure and development of social movements but also ties into their socio-technical security, where understanding how individuals navigate and interact within socio-technical systems is crucial for effective cyber measures. While it is tempting to discuss technological frameworks as deterministic to recordkeeping behaviours, a community’s political needs also imbue and better shape recordkeeping infrastructures. Power structures have developed restrictive and imbalanced records frameworks (exemplified in places like government archives) but these systems can be used by, informed by and potentially disrupted by activist actions.

In the context of the animal liberation activist movement, individuals and groups can perform direct action and strategic witnessing recorded in time to collectively make changes in law; aiming to change the course of history. Long-term preservation systems, practices and infrastructures must be developed to support these goals and recordkeeping structures to continue to support actions across time and space in the activist network. Strategic witnessing is used to evidence wrongdoing and the need for change in and over time. With risk-assessed and long-term retention in place for recordkeeping, a movement can confidently retain that evidence for memorialisation of action. The retention of records also aids in knowledge building that adds to a case for social change. The structure of an activist group and its systems give agency to its members to perform recordkeeping in a trusted way. The structures of these networks inform the performance and relationships across the activist and public networks. Radical recordkeeping through evidence and memorialisation can change society.

Risk Hermeneutics in Animal Activism

Action and structure are two sides of the same coin. Actors can express their self-determination in platforms that conversely guide their behaviour, working within the rules of that platform. Structuration theory explores the relationship between agency and structure, and the environments where activists create records can be viewed as simultaneously empowering and disempowering. Recordkeeping within an environment of simultaneous emancipation and restriction is performed consciously activism in their knowledge of limitations in popular platforms. For example, members have the flexibility to use Google Docs, but are also at the mercy of the Google corporation and rely on having the frameworks for recordkeeping in relation to design, reliability and security of their records in Google Drive. Agents and agency are familiar terms in sociology and linking to the performative agency of individuals and groups. Actions are dictated by the social structures, group understandings, or roles within the group and access controls are created in line with these community understandings.

The risk hermeneutic is a newly derived term to describe risk-taking or assessment. Elsewhere, risk-taking is a social phenomenon understood in psychological terms.[5] Risk-taking is not often discussed in a technological sense when choosing recordkeeping styles for activist recordkeeping platforms. As activists have a growing understanding of overt and covert surveillance, there is increasing knowledge of risk. There is potential behaviour change in reaction to perceived threats and how to avoid or decide to embrace them. For example, in assessing the risk in creating a record or not, such as creating a video with member identities shown, actors evaluate the risk in the whole and sum of parts. There is a risk of reprisal by being unmasked, either from the agriculture industry or anti-activist sentiment. The risk of losing momentum in the movement by hiding behind anonymity is an appraisal decision around trace, revelation or obfuscation.

In hermeneutics, there is the understanding that others’ experiences are individually interpreted within a complex layered social context.[6] Witnessing enables others to relive an experience, but this experience speaks through the lens of the individual or group. By evidencing events and providing a narrative to describe these events in the activists’ own words, demonstrates that actors are emancipated beyond a viewer or spectator role in political life. Democratisation of citizen politics, with witnessing one way to allow for citizen narrativity, means there are new ways of societal participation against dominant systemic restrictions to entry into governmental debates. To interpreters of a record it may be risky in their view to create and maintain evidence, but to activists, potential threats outweigh the benefits of taking that risk. The risk assessment of using platforms that censor, police and animal activist interactions and memorialisations are risky prospects.

At a Recordkeeping Roundtable event in 2021, attendees were encouraged to “let go of functionality that isn’t there and exploit the functionality that is there”,[7] for the systems of records created in organisations. The same is true for an activist group. Facebook provides the functionality for the here and now. The impact of recordkeeping as a political platform to evidence witnessing can mean risk-taking is involved. As seen in many social movements, achievements were often gained by taking risks or being put in jail. Activists use radical recordkeeping to highlight an unjust system and inequity – and they use the assessment of threats alongside the willingness to take risk for societal change and benefit to the animals.

Archiving is a political act. During the development of this book, activist citizen witnesses of human rights abuse Lokman Slim (to name just one) was assassinated for witnessing and archiving. “Lokman Slim was a Lebanese human rights defender … archiving material needed for the upholding of the Lebanese people’s right to memory, truth, justice and redress”.[8] While somewhat safe from assassination,[9] animal activist groups are emancipated from silence but accept personal and group risk. To witness using technologies that reach a supportive (and a not so supportive) audience is still threatened by outside forces that aim to silence, eradicate and criminalise activist witnessing.

Memory is not always spoken, and silence is not necessarily forgetting. Sometimes silence is a way survivors protect themselves from harm, particularly when their memories contradict metanarratives of victimhood or when they are stigmatized.[10]

In discussing the risk of recording, self-protection, for dependents as well as the community can come together as part of an appraisal decision. The concept of risk to self, emotion-based decision making, can extend to the idea of Jacques Rancière’s “emancipated spectators”.[11] To Rancière, democracy begins with an equalising uprising against policing when established social frameworks are contested.[12] Radical agents legitimise their authority of voice, where it was previously undervalued or undermined by the systems of politics that suppress activist communities.[13] What is new to the archival discourse here[14] is the performance of witnessing and radical recordkeeping to support a critical continuum view of action over space and time. Activists are emancipated from passivity through political action. However, networked global witnessing remains confined by the recordkeeping systems and platforms that society creates for them. Through action and change over time, the dynamics of structuration theory plays out, not just through activist archiving practice, but also through learning from these practices. This learning can lead to rethinking, redefining and redesigning recordkeeping infrastructures. Changes made can inform and be informed by existing risk management and decision-making (aka appraisal). Critical infrastructures can be developed that assess inherent risk and embed values of witnessing, social change and action to influence behaviour to best support strategic witnessing and be shaped by the activist community themselves.

Grappling with cause and effect of restriction and emancipation is also at the heart of Giddens’ Structuration Theory. Giddens situated action and structure together in a hermeneutic spiral.

… by engaging into different social practices and behaviours, agents produce and reproduce social structures in an ever-flowing circle or, better conceptualised, a spiral which repeats over and over again. Agents draw upon social structures in order to act and, at the same time, they reproduce these same or slightly altered structures, which in the end, are established as the new conditions of action for the next cycle of the structuration process.[15]

These “slightly altered structures” are informed by activism and risk-taking. Whether slowly or radically transformed, political influence over time is described by Moyer’s Movement Action Plan[16] and intertwines with witnessing and recording action performance. This emphasis on action informs appraisal, emphasising recordkeeping for political and collective action. Participation, action and performative recordkeeping are politically charged traces. Building on this, performance, action and participation are themes running through the re-thinking of appraisal in later chapters.

Archives are spaces in which collective knowledge and memories of political struggles can be cultivated and mobilised for use in contemporary campaigns. Such autonomous, activist archives are key sites for bridging the past, present and future for social movements. However, the significance of these archives does not lie only in their use in constructing (and intervening in) social history that challenges official narratives. These are living archives, which operate as spaces of experimentation and collaboration in which emerge alternative archival practices. These in turn create, organise and support different and often collectivised, knowledge claims. Thus, the formation and activation of activist archives may be viewed as one strategy, among others, to challenge and transform hegemonic political power and open up alternative collective possibilities.[17]

Functional Appraisal and Analysis

An organisational functional analysis of an animal activist group was conducted according to the International Standard for Recordkeeping ISO15489[18] using research interview data from 2017-2023 and document analysis. The steps taken were based on the DIRKS Methodology which provides more detail to the International Standard.[19] In using and critiquing the process throughout the data collection, a case for a Critical Functional Analysis was also developed throughout the case study analysis, explored later in chapter seven. As a method for research, DIRKS methodology outlines practical steps for “Understanding the business, regulatory and social context (Step A)” and the need to

– Identify [an agency’s] need to create, control, retrieve, and dispose of records (that is, their recordkeeping requirements) through an analysis of their business activities and environmental factors (Steps B & C)

– Assess the extent to which existing organizational strategies (such as policies, procedures, and practices) satisfy their recordkeeping requirements (Step D).[20]

These steps are used here as a gateway to understanding the case, critiquing the DIRKS approach for a social movement. To test the traditional analysis methods against non-traditional case, the functions of an animal activist group were analysis according to the process in the DIRKS manual.[21]

Parts of the DIRKS methodology related to business recordkeeping needs were used, attempting to impose the ideas of business analysis to an animal activist group. Finding functions of the group itself, highlighted its inability to address in full the needs and values central to the functions of this group which embraces activities such as open rescue of animals. This realisation and testing led to the need for a critical approach to functional appraisal.

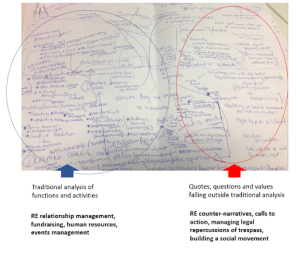

Fig. 6.2 Traditional Functional Analysis and the Note-taking of Anomalies and Shortfalls in the Process.[22]

image description

Figure 6.2 above depicts the approach to determining animal liberation functions, looking at policies, procedures and processes from document analysis. The sections below outline each side of Figure 6.2: the traditional analysis (in blue) and the complexity of the grassroots context falling outside a typical organisational analysis (in red). The note-taking around traditional functions specific to one animal activist group, is represented by the blue circle on the left. The red circle shows that the traditional functional analysis has gaps in describing important functions to an animal activist group. The second half of the chapter focuses on the analysis in the red circle of Figure 6.2, where questions around taking measured risks, acting on emotions and values of the group that did not fit neatly into the left hand side of traditional analysis. The left-hand side includes: organising events, fundraising and strategy development are examples of functions and activities relatable to business analysis. While they are a community group, activism does have functions of what could be labelled ‘finance’ and ‘recruitment’ – however, these operate in ways specific to their activism. Donations and recruitment of new members are part of the growth of the grassroots community within a broader social movement, and as such, are intertwined with the ‘direct action’ that the group promotes. Financial management is primarily managing donations. Marketing focuses on promotions of campaigns and sharing successes in-person and online. Recruitment is linked to the sharing of success to inspire the growth of member numbers to join the movement and direct actions worldwide.

There was an obvious disjunction between the ‘business systems’ focus of functional analysis and the anti-corporate stance of an animal rights group. The development of functional analysis was influenced by business analysis.[23] What cannot be seen in these steps is that the functions of direct action are laden with emotion, values and desire for social change, which are separated out to the right-hand side of Figure 6.2. The traditional functions surfaced by this analytic process (on the blue/left hand side of Figure 6.2) are highlighted in Figure 6.3 below.

DIRECT ACTION a Function of Animal Liberation, with the Following Activities:

(Other Supporting Functions/Activities: Animal advocacy; Direct action training; Sharing ideas & sharing animal and activist experience; Service and systems strategy; Community building events and meetups; Fundraising; Campaigns and communications [Social media, Website, Videography, Truth-telling narrative, Collaborations and media]; Chapter management) |

Fig. 6.3 Overview of the Direct Action Function of an Activist Group.[24]

Social change and animal liberation is a driving purpose of this case study activist group supported by the functions and activities in Figure 6.3 above. Whilst there are administrative functions that group performs (in brackets), it is the dot-point direct action activities that are core to the values and goals for social change within the movement. Direct action is an overarching descriptor of the group enacting social change – and direct action can be considered an umbrella term. These purposes and functions are ambient across other animal rights groups and are not unique to this group alone. Similarly, functions like community building and truth-telling are about building their community as well as the broader animal liberation movement. However, for the purpose of this case study at the ‘organisational (or group)’ level of the continuum, it is acknowledged here that the uniqueness of this one group in particular (Direct Action Everywhere) lies in campaigning for activist right to rescue and disruption through non-violent direct action.

Figure 6.3 is the outcome of systemic analysis of Direct Action Everywhere’s activity (from both the interview and document analysis) and has an emphasis on the ‘business activities’: with an attempt to fit them to grassroots terms (e.g. Finance = Fundraising; Marketing = Campaigns). But as Figure 6.2 shows, doing this analysis raises more questions than it answers, with a business analysis approach of DIRKS proving inadequate to capture the nuances of the group’s values, relationships, community focus and decision-making in its direct action. While it was not a perfect exercise in meeting the needs for categorising potential future appraisal, it did provide some lessons for what is needed to transform traditional functional analysis methods.

Acknowledging Emotion

The example of Direct Action Everywhere has been used as an example of living archives or “emergent community archives”.[25] In these descriptions of a corpus of knowledge, power, values and emotion are intertwined. However, emotional aspects are often separated from the analytic, sidelined to the realm of the illogical or unreliable actor or spectator in some worldviews.[26]

For decades, the study of protest movements largely neglected the role of emotions, overshadowed by rationalistic, structural and organisational models that dominated political analysis. Emotions were relegated to the background, perceived as irrelevant to the ostensibly rational sphere of political action. However, it is becoming increasingly clear to some that a new theoretical framework is necessary – one that acknowledges and integrates the significant role of emotions. Activists often strive to project a rational and strategic image to the outside world, emphasising their instrumental value in political change. Yet, internally, organisers openly acknowledge and employ emotional techniques to foster solidarity, loyalty and love among members, aiming to make participation a rewarding and enjoyable experience. Externally, protest leaders seek to influence the emotions of outsiders, eliciting feelings of compassion, anger, outrage and fear to galvanise support and action.[27] Historically, mobilisation theorists adhered to a stark dichotomy between rationality and emotion, largely dismissing the latter in their analyses of political movements. This perspective ignores the complex interplay between emotional and rational motivations in political activism. In the wake of the cultural turn in social sciences, we are now beginning to recognise and reassess the role of emotions in a more nuanced and productive manner. Emotions are no longer viewed as antithetical to rational political action but as integral components that can enrich our understanding of protest dynamics. This shift promises to yield more comprehensive and insightful theoretical models, bridging the gap between the emotional and rational dimensions of political engagement.[28] Authors are beginning to explore the intersection between political theory and archival studies, particularly through the lens of community appraisal models.[29] Drawing on the insights from political movements and the role of emotions, this work proposes a framework where archival practices are deeply intertwined with the dynamics of activism and community engagement. The connection between political modeling and archival studies in this context lies in the recognition that both disciplines can benefit from a more integrated approach to understanding and valuing both emotional and rational dimensions. Just as political theorists have begun to appreciate the significant role of emotions in mobilising support and driving political change, archivists can similarly acknowledge the emotional and subjective aspects of community appraisal. This means considering how emotions influence the creation, preservation, interpretation of archival materials and recognising that archives are not merely repositories of objective facts but are also shaped by the emotional and cultural contexts of their communities.

Conclusion

Applying records continuum theory to a critical appraisal approach for politically charged groups like animal activists, emphasises the need for a human-centered approach to functional analysis. The application of hermeneutics reiterates the importance of understanding the decision-making processes of individuals and the broader societal impacts on appraisal, particularly in the memorialisation and forgetting of events. This is essential for respecting and enabling empowered community recordkeeping practices. By embodying structuration hermeneutics, continuum theory acknowledges that individual actions and recurrent social practices shape recordkeeping across various dimensions. The hermeneutic circle, or spiral, illustrates the continuous interplay between smaller and larger units of meaning, providing a holistic understanding of societal relationships, community dynamics and individual agency within a political context. This nuanced approach to appraisal, reflecting the creation, influence and societal structures behind records, is crucial for understanding the complex interplay of memory, action and political change. As demonstrated in the analysis of animal liberation activists, the development of long-term preservation systems and strategic witnessing practices highlights the transformative power of radical recordkeeping in driving social change and challenging hegemonic power structures.

The following sections of this book propose appraisal models that are not only technically rigorous but also sensitive to the emotional and political undercurrents within communities. By applying these principles, archival studies can develop more inclusive and representative appraisal models that better capture the lived experiences and emotional landscapes of the communities they serve. This fusion of disciplines enriches both fields, offering a more holistic view of how archival practices and political activism can mutually inform and strengthen each other.

- Motahari, Mohammad. 2008. “The Hermeneutical Circle or the Hermeneutical Spiral?” The International Journal of Humanities15 (2): 99–111. ↵

- Gijsbers, Victor. 2017. “Chapter 4.1: The Hermeneutic Circle.” Leiden University, YouTube. 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIEzc__BBxs. ↵

- Pleasants, Nigel. 2019. “Free Will, Determinism and the ‘Problem’’of Structure and Agency in the Social Sciences.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 49 (1): 3–30. ↵

- Bontekoe, Ronald. 1996. (Used with Permission) Dimensions of the Hermeneutic Circle. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International, p.4. ↵

- See for example Trimpop, Rüdiger. 1994. The Psychology of Risk Taking Behavior. Vol. 107. Advances in Psychology. Elsevier. ↵

- Bagguley, Paul. 2013. “Chapter 3: Beyond Emancipation? The Reflexivity of Social Movements.” In Theorising Modernity: Reflexivity, Environment and Identity in Gidden’s Social Theory, edited by Martin O’Brien, Sue Penna and Colin Hay. Oxfordshire, England; New York: Routledge. ↵

- Cumming, Kate and Panel. 2021. “Recordkeeping Theory, Models & Strategies and Today’s Workplace.” Recordkeeping Roundtable. April 2021 (quoting Andrew Waugh). ↵

- Front Line Defenders. 2021. “Killing of Human Rights Defender Lokman Slim.” 2021. https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/case/killing-human-rights-defender-lokman-slim. ↵

- A profile of seven activists killed during their protest activity, including animal rights activists is memorialised by the Animal Save Movement website (Harris, A., n.d., 7 Inspiring Activists Killed by The Animal Agriculture Industry. Retrieved October 10, 2022. Animal Save Movement website: https://thesavemovement.org/seven-inspiring-activists-killed-by-the-animal-agriculture-industry/). ↵

- Riano-Alcala, P, and E Baines. 2011. “The Archive in the Witness: Documentation in Settings of Chronic Insecurity.” International Journal of Transitional Justice, 5 (3): 412–33, p.429. ↵

- Ranciere, Jacques. 2011. The Emancipated Spectator. Reprint. London: Verso. ↵

- Mayer, Seth. 2019. “Interpreting the Situation of Political Disagreement: Rancière and Habermas.” Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy 27 (2): 8–31. ↵

- Feola, Michael. 2019. “Excess Words, Surplus Names: Rancière and Habermas on Speech, Agency, and Equality.” Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy, 27 (2): 32–53. ↵

- extended in: Howard, Mark, Katherine Jarvie and Steve Wright. 2021. “Rancière, Political Theory and Activist Community Appraisal.” Archives and Manuscripts, 49 (3): 1–20. ↵

- Perales Perez, Francisco. 2008. “Determinism and Voluntarism in Giddens’s and Bourdieu’s Theories of Human Agency.” Essex Graduate Journal of Sociology, January. ↵

- Moyer, Bill. 1987. “The Movement Action Plan: A Strategic Framework Describing the Eight Stages of Successful Social Movements.” History Is a Weapon, 1987. ↵

- Pell, Susan. 2015. “Radicalizing the Politics of the Archive: An Ethnographic Reading of an Activist Archive.” Archivaria, 80 (Fall): 33–57, p.38. ↵

- Standards Australia. 2017. “AS ISO 15489.1-2002 Information and Documentation - Records Management - Part 1: Concepts and Principles.” International Standards. ↵

- State Records NSW. 2017. “DIRKS Methodology and Manual.” State Archives and Records New South Wales. 2017. https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/recordkeeping/advice/dirks/methodology now archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170310023638/https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/recordkeeping/advice/dirks/methodology. ↵

- Standards Australia. 2017. “AS ISO 15489.1-2002 Information and Documentation - Records Management - Part 1: Concepts and Principles.” International Standards. ↵

- Standards Australia. 2017. “AS ISO 15489.1-2002 Information and Documentation - Records Management - Part 1: Concepts and Principles.” International Standards. ↵

- Jarvie, Katherine. 2023. “Radical Recordkeeping — Re-Thinking Archival Appraisal.” Monash University. ↵

- Stephen, Mcintosh and Real Lynne. 2007. “DIRKS: Putting ISO 15489 to Work .” Information Management Journal, 41 (2): 50–56, p.50. ↵

- Jarvie, Katherine. 2023. “Radical Recordkeeping — Re-Thinking Archival Appraisal.” Monash University. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2019. “Connecting Personal and Community Memory-Making: Facebook Groups as Emergent Community Archives.” In Proceedings of RAILS 28-30 November 2018, 24(3):1804. Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia,: Information Research. ↵

- Howard, Mark, Katherine Jarvie and Steve Wright. 2021. “Rancière, Political Theory and Activist Community Appraisal.” Archives and Manuscripts, 49 (3): 1–20. ↵

- Goodwin, Jeff, James Jasper and Francesca Polletta. 2000. “The Return of the Repressed: The Fall and Rise of Emotions in Social Movement Theory.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 5 (1): 65–83, 65-6 ↵

- Goodwin, Jeff, James Jasper and Francesca Polletta. 2000. “The Return of the Repressed: The Fall and Rise of Emotions in Social Movement Theory.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 5 (1): 65–83, 80-1 ↵

- Howard, Mark, Katherine Jarvie and Steve Wright. 2021. “Rancière, Political Theory and Activist Community Appraisal.” Archives and Manuscripts, 49 (3): 1–20. ↵

"... hermeneutics can provide both a way of analyzing the creation of meaning through the interpretation of texts ... Further, while hermeneutics is not specifically concerned with the performative aspects of language as such, it can provide a mechanism for understanding the ways in which participants in virtual communities build their communities through interpretive acts or, more accurately, through interpretation made manifest in acts of writing [or not] in response to other writing."

Or in risk hermeneutics, can be community action described in relation to animal activism protections, learning and adapting, in response to active threats.

Burnett, Gary. 2002. “The Scattered Members of an Invisible Republic: Virtual Communities and Paul Ricoeur’s Hermeneutics.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 72 (2): 155–78.

"Instead of describing the capacity of human action as being constrained by powerful stable societal structures (such as educational, religious, or political institutions) or as a function of the individual expression of will (i.e., agency), structuration theory acknowledges the interaction of meaning, standards and values, and power and posits a dynamic relationship between these different facets of society."

Gibbs, B. J. 2017. Encyclopedia Britannica (accessed 2017) https://www.britannica.com/topic/structuration-theory.

The term sense-making here encompasses the sense-giving to others in a group and its potential to tell that disruptive narrative beyond the individual or sub-group.

In an analysis of the People of Ethical Treatment of Animals’ YouTube content, sense-making has been applied to activism, describing the People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA)’s disruptive action as

… an attempt to convey highly disruptive issues to a wide audience through numerous micro-episodes (e.g., through media and social media platforms). These episodes constitute sensegiving attempts to “influence the sensemaking and meaning construction of others toward a preferred redefinition of … reality” (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 442). These attempts trigger sensemaking … (Hu & Rerup, 178).

References

Gioia, Dennis A., and Kumar Chittipeddi. 1991. “Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation.” Strategic Management Journal, 12 (6): 433–48.

Hu, Yanfei, and Claus Rerup. 2019. “Sensegiving and Sensemaking of Highly Disruptive Issues: Animal Rights Experienced through PETA Youtube Videos.” In Microfoundations of Institutions, edited by Patrick Haack, Jost Sieweke, and Lauri Wessel, 177–95. Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Emerald Publishing Limited.

..." a framework through which we can think about the politics of media witnessing as dependent upon audience differentiation, which activists utilize as a tactical apparatus geared toward social change."

Ristovska, Sandra. 2016. “Strategic Witnessing in an Age of Video Activism.” Media, Culture and Society, 38 (7): 1034–37.

Where risk is assessed in an iterative way in relation to context and experience, changing and adapting to threats and influencing decision-making related to risky action.

"… disruption of traditional recordkeeping paradigms in revolutionary or profound ways by groups and recordkeeping and archiving professionals who challenge or disrupt social or mainstream norms."

Jarvie, Katherine, Greg Rolan, and Heather Soyka. 2017. “Why ‘Radical Recordkeeping’?” Archives and Manuscripts, 45 (3): 173–75, p.173.

A function is 'a set of related and ongoing activities of the business' [or community activist group]. Functions represent the major responsibilities that are managed by the organisation to fulfil its goals. Functions are high-level aggregates of the organisation's activities.

Standards Australia. 2017. “AS ISO 15489.1-2002 Information and Documentation - Records Management - Part 1: Concepts and Principles.” International Standards.

"During a typical open rescue, animal activists simply walk onto farms and remove animals showing signs of distress ... Walking onto farms is done openly, without masks, without violence and without property damage."

Scott-Reid, Jessica. 2023. “The Open Rescue Movement for Farm Animals, Explained.” Sentient Food. October 19, 2023. https://sentientmedia.org/open-rescue-movement/.

"Grassroots activism is about mobilizing a group of people, who are passionate about a cause and harnessing the power of their conviction to push for a different outcome. This kind of movement relies on individuals who are willing to drive the change that they are concerned about from the ground up."

Swords, Jojo. 2017. “Grassroots Activism: Make That Change.” Thoughtworks Thailand. November 16, 2017. https://www.thoughtworks.com/en-th/insights/blog/grassroots-activism-make-change.

"Ambience is the context of provenance ... Functions offer one possible tool for crafting ambient relationships. Ambient functions define and give meaning to agents of record-keeping within the context in which they operate."

Hurley, Chris. 1995. “Ambient Functions - Abandoned Children to Zoos.” Archivaria 40 (June): 21–39.

One example of this ambience is having a shared context of animal liberation activism. Chris Hurley’s multiple simultaneous provenances are occurring at a group level for activist group Direct Action Everywhere (DxE), but individuals and the broader movement are also co-creators and stakeholders in DxE records (at an ambient level). Hurley’s description of ambience can also be applied in the animal activism context for ambient identity and ambient purposes.

"Living archives are traditionally understood as appraising and collecting activist historic representation re-lived and re-performed over time. There is a developing understanding of what now constitutes a living archive which can be re-thought alongside radical recordkeeping."

Howard, Mark, Katherine Jarvie, and Steve Wright. 2021. “Rancière, Political Theory and Activist Community Appraisal.” Archives and Manuscripts, 49 (3): 1–20.