3 Recording a Movement Over Time – Animal Liberation

Animal activism is an exemplary case to demonstrate the benefits of continuum-based appraisal due to the movement’s dynamic and evolving nature. A records continuum approach to appraisal of this activist recordkeeping recognises these acts as part of an ongoing process, accommodating the diverse activities and evolving strategies within the movement. By considering the interests of multiple stakeholders and leveraging of digital records, continuum-based appraisal can help achieve a comprehensive and holistic representation of animal activism, capturing its diverse scope and ongoing significance.

The integrated role and benefit of records in animal activism is demonstrated by direct action tactics. Examples of direct action include live streaming of actions and protests, and creating records that reach a target audience in real time to uncover wrongdoing by big ag. Longer undercover investigations of big ag or short-term disruptions to events like hot dog eating contests are other examples of direct action.

Direct Action

Direct action is a strategy used by animal activists to bring attention to the mistreatment of animals and push for change in society. It involves actions that directly challenge existing laws or practices in order to reveal problems and influence public opinion and politics.[1] These actions, often involving civil disobedience, take place in spaces like restaurants, stores and farms. Activists can use a tactic called open ‘rescue’, where they film themselves rescuing animals from factory farms, to raise awareness and create a sense of urgency about animal welfare issues.

By documenting these actions, activists create records that disrupt societal norms and challenge people’s moral values. They aim to show that animals deserve respect and consideration, just like humans. This form of recordkeeping is crucial as it helps to highlight the plight of animals and drive change in how society views and treats them. Online open rescue videos are an example of records of non-human animals. These records are always becoming over time – which means they are shared live online, reshared, re-edited, reused in media and in the social media spaces of individuals and communities (both supportive and oppositional). These records ‘always becoming’.

Animal activists use online platforms to record their actions. Leisa Gibbons has explored Facebook groups as emergent community archives[2] and these spaces serve as inspiration and background to understanding recordkeeping by an animal activist community[3] have considered online platforms as another form of record series (therefore, a form of a digital bundle).

Photo by Jorge Maya on Unsplash

A bundle or platform as a container suits community contexts since the knowledge represented does not need to mimic a business archive of a traditional recordkeeping structure. Acknowledging real-time community archiving on platforms is only in its infancy in the archival literature, but has interdisciplinary reach for YouTube as archive in particular[4]; as a probability archive[5] accidental archive or living cultural archive[6] at risk of loss. In a recent example, there is recognition of Reddit as an immediate archive and that the longevity of these records is at risk.[7]

The philosophy behind this activism draws from influential works like Peter Singer’s book Animal Liberation,[8] which advocates for recognizing the feelings and rights of non-human animals. Activists from different countries collaborate and share knowledge to evolve their tactics and strategies for animal liberation. By employing radical recordkeeping and direct action, animal activists strive to uncover the truth about animal suffering and drive positive changes in how we treat and respect all living beings.

Transnational Recordkeeping Across Geographies

Transnational animal activism[9] manifests through various networks, characterised by voluntary, reciprocal and horizontal communication. These decentralised structures are crucial in fostering collaboration and coordination among individuals advocating for causes such as animal liberation. While some groups eschew formal organization, governance models often underpin their activities to ensure effective coordination. Participants in these networks may hold diverse beliefs, yet they unite under common goals, such as advocating for veganism or animal rights.

The transnational nature of activism is evident in the evolution of direct-action techniques, with practitioners across borders sharing insights and strategies. Documenting successes and methodologies becomes a crucial tool for empowering future activists and sustaining momentum for social justice causes. Transnational activism encompasses various forms of contentious collective action, as outlined by Sidney Tarrow, which involve challenging authorities or powerful opponents through confrontational means.[10] These actions, part of what Tarrow terms “repertoires of contention,” can range from performative and disruptive protests to more organised and resource-intensive strategies. Resource Mobilization Theory (RMT), initially proposed by McCarthy and Zald, offers a framework for understanding how social movements acquire and utilise resources to achieve their goals.[11] Originally, RMT focused on traditional forms of organization and mobilization of activist groups, but with the advent of transnational and online developments, the theory has evolved to encompass broader dynamics within social movements. while Resource Mobilization Theory originated with a focus on traditional activist group organizing, it has evolved to encompass the influence of transnational and online developments on social movement dynamics. Contemporary interpretations of RMT acknowledge the importance of these factors in shaping how movements mobilise resources and reach new audiences in today’s globalised and digital world. Archival theory can adapt to these changes too, reflecting the values and ideologies of activist communities and their networked, digital and evolving means to appraise records for use, re-use and transnational societal change.

Repression of Open Rescue Records of Activism

Direct action methods for animal activists include open rescue. Activists have risked fines and jail time, with legislation across jurisdictions either changed or introduced over time to increase the likelihood of convictions. These barriers hinder systemic change sought by activists. The early animal activists in Australia performing open rescue had “paper trails” of their activity that could send them to jail (but they still embraced the openness of action).[12]

What have become to be known as ag-gag laws are a key hindrance to open rescue. In the 1990s, the gagging of activists protesting big ag using legislation as punishment started to gain prominence.[13] Ag-gag laws criminalise unauthorised recordings and photography of animal industries for “interfering with operations of an animal enterprise”.[14] The origin of ag-gag in the United States stems from threats to the American way of life, religious ideals, culture and capitalist governance.[15] In the 1980s, the American Medical Association released its Animal Research Plan, which claimed animal activists were “a threat to the public’s freedom of choice”.[16] Animal experimenter Edward Walsh “argued that even simple acts such as not wearing fur, eating meat or attending rodeos “quietly, but effectively, promote the dissolution of our culture … all animal rights terrorists should be treated harshly”.[17] A 2008 Department of Homeland Security report claimed that “Animal rights and environmental movements directly challenge civilization, modernity and capitalism” and could ultimately lead to “anti-systemic” governance.[18]

Ag-gag law is a contemporary embodiment of what historian Richard Hofstadter called a “paranoid style” of politics,[19] where the powerful protect their interests with fear of attack on civil rights, since “nobody will be able to eat meat, wear fur, take life-saving medication [or] enjoy circuses”.[20] This same legislation has reached Australia, evidenced by a successful Surveillance Devices Act Government of South Australia. [21] and New South Wales.[22] This legislation affects Australian open rescue methods and other non-violent methods of protest that inform social movement tactics and are escalating forms of state repression.[23] Ag-gag laws aim to deter activists from disseminating video evidence and means that “Taping of Farm Cruelty Is Becoming the Crime”.[24]

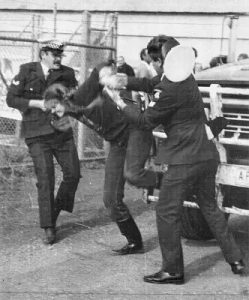

Fig. 3.1 Patty Mark being arrested for her activism c.1980.[25]

Open rescue by Patty Mark, founder of Australia’s Animal Liberation Victoria was broadcast on the 1990s current affairs TV show Hinch[26] and led to a court case in the hopes of holding farmers to account for cruel animal conditions. However, in November 1994

… hopes were quickly dashed when the magistrate ruled that photographs, video footage, and [Patty] Mark’s testimony were inadmissible as evidence because they were illegally obtained. Without that important evidence, cruelty charges could not be substantiated. The court case was over. The limitations of the legal system were painfully revealed. While the idea of legal prosecution was not wholly abandoned, it was a tactic that was inconsistent and difficult to achieve.[27]

Since this case, Will Potter’s book Green is the New Red[28] provides a detailed view of state repression of animal liberation activity and is an insightful account of the challenges activists face under ag-gag legislation. Such legislation can “carry a terrorism conviction despite absence of violence”.[29] Even before the tougher amendment of the US Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, in 2004, sixty crimes were labelled as eco-terrorism in the United States.[30] There was hope during the Obama administration from 2009 that such labelling of animal activists as eco-terrorists would subside.[31] However, ag-gag’s influence continues to grow. US laws threaten activists with “decades in prison”.[32] Activists performing direct action in Spain, too, have been judged by courts and media as performing acts of eco-terrorism.[33] Under ag-gag laws, gaining employment for whistleblowing is an offence[34] which is problematic legislation for genuine workers who uncover animal mistreatment.

Nevertheless, activists proceed with covert surveillance and open rescue to uncover the truth, despite the risks of ag-gag legislation. Animal activists want ag-gag law repealed,[35] but support by governments continues. Battery cages, for example, are lawful; animals are seen as the property of humans and agriculture is part of economic and cultural reality. The failed legal cases against the agriculture industry have “reinforced the property status of animals and established legal obstacles that were counterproductive to the open rescue method”.[36] Still, many activists are willing to sacrifice their freedom for the cause of animal liberation.

Direct action as an activism tactic (to share, develop and record) highlights the importance of recordkeeping to help change societal attitudes. Animal activists use recordkeeping as part of their tactics for social change. The reasons for documenting traces of actions inform the definition and understanding of what radical recordkeeping means to this disruptive community. This idea is discussed in the next chapter. Activists create records under oppression from their legal, socio-political and technological environment where law permeates “affairs of humanity [and non-human persons] in every realm”.[37] The records reflecting power and counter powers between the law and activism are invaluable to understanding the role and risks of recordkeeping. The implications of these power struggles on appraisal, for records retention over time, are explored in later chapters of this book.

What advice do Activists have About Appraisal?

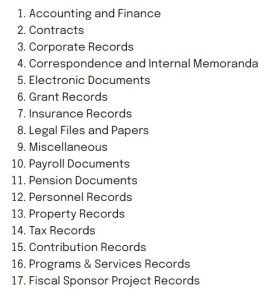

The only appraisal advice for activists found during this research attempts to mimic traditional bureaucratic retention and disposal schedules. Figure 3.3 is an example from a legal source that advises human rights activists on records retention focusing on the records activists need to keep for legislative reasons. However, these categories not only focus on the records themselves rather than the functions they perform, but categories like ‘electronic records’ are also impractical and ineffective as a differentiating indicator of permanent retention for a predominantly online activist group.

Fig. 3.3 Retention and Disposal Advice for Activists.[38]

Figure 3.3 shows overarching categories for consideration by activists, but important videos of direct action are not included in this legal advice to activists, except under the broad umbrella of ‘electronic records’. There is no specific appraisal advice related to these dynamic records, which means there is a risk that grassroots animal activist groups mimic corporate appraisal models that do not suit their activities. Within the community itself, there is advice online and within groups on how to create records and avoid risk, but less on long term strategies for retention.

Records of Networked Communities

Records created by animal liberationists in a broader social movement are connected in the collective and individual values of its members, all fueled by the common goal of ending animal suffering. Distributed recordkeeping across a network of communities, via social media and online visual tools, are crucial instruments for emotive storytelling. Activists actively engage in recordkeeping, utilizing various online platforms to document disruptions, sometimes livestreaming to their members and followers, from places like restaurants, retail stores and factory farms, drawing attention to their cause.

Online platforms serve as a dynamic space where activists coexist, interact and share their experiences within the broader animal rights movement. Individuals and groups make decisions, both personal and collective, contributing to a networked archival multiverse. The use of multiple platforms strengthens global communication and facilitates the expansion of the movement across social and geographic boundaries. Promotional videos exemplify records that are in a state of constant evolution, shared live, reshared, re-edited and reused across various media and social spaces. These evolving records mirror the complexity and adaptability of the broader social movement.

A digital bundle serves as a container for community-generated knowledge, narratives and experiences, reflecting the shared values and goals of the networked community.

Key characteristics of a digital bundle in the context of networked communities include:

- Online Platforms as Containers: Digital bundles are often hosted on online platforms such as Facebook groups, YouTube channels, or other social media spaces. These platforms act as containers for diverse records, including videos, images, posts and discussions, providing a dynamic space for the community to document and share their activities.

- Dynamic and Evolving Content: Unlike traditional record serieswith static content, digital bundles are characterised by their dynamic and evolving nature. Records within the bundle are subject to constant reshaping, sharing and re-editing across different media and social spaces. This reflects the adaptability and responsiveness of the community to emerging issues and challenges.

- Emergent Community Archives: Digital bundles can be seen as emergent community archives, capturing the collective experiences and actions of the activist community. These archives form organically as members contribute to the ongoing narrative, creating a rich repository of records that tell the story of the movement over time.

- Global Communication and Collaboration: The use of multiple online platforms strengthens global communication and facilitates collaboration across social and geographic boundaries. Activists actively engage in recordkeeping, utilizing various platforms to document disruptions, livestream events and share knowledge, fostering a sense of connection within the broader animal rights movement.

- Multifaceted Record Types: A digital bundle encompasses various types of records, including videos, images, blog posts, news interviews and promotional materials. This multifaceted approach allows the community to express their activism through different mediums, reaching diverse audiences and contributing to the movement’s overall visibility.

- Resilience Against Repression: In the face of legal challenges, such as ag-gag laws, digital bundles become crucial tools for resilience. Activists continue to document and share their actions despite legal risks, emphasising the importance of recordkeeping as a form of resistance against repression.

Understanding the concept of a digital bundle in the context of networked communities provides insights into the evolving landscape of recordkeeping within contemporary social movements. It highlights the interconnections, adaptability and collaborative nature of record creation and sharing in the digital age.

Values-based Appraisal Decisions

Core beliefs within the animal liberation movement are often articulated through a set of values, serving as guiding principles for activists. These values act as a framework for current members and an introduction for potential ones, setting expectations for participation in the collective activism. Integrity, responsibility, and other foundational principles are embedded within expected values, and are subject to change and review by the members themselves, reflecting the evolving nature of the movement over time.

Recordkeeping is a crucial tool for capturing, creating and pluralizing values across the activist community. These records serve as traces within a complex network, documenting milestones and sometimes conflicting viewpoints among activists. They support communication, ensuring continuity, emoting solidarity and preserving the emotional connection built over time, as highlighted through interviews with community members.

Activist records, laden with values, evoke strong emotions, strategically harnessed to tell powerful stories. Emotions play a pivotal role in the activist community, prompting reflection and action. The use of emotions, can become a tool for change, challenging societal norms and inspiring activism for the cause.[39] Activist records go beyond mere documentation; they embody the collective emotional journey of activism. Videos, photographs and other mediums serve as milestones, documenting successes and challenges in the broader social movement. Emotionally charged records contribute to the overarching goal of animal liberation and have the potential to counter detractors’ views.

Disruptions, Micro-disruptions and symbolic actions can generate awareness if done wisely, finding tactics that establish ongoing community support. Hashtags and online platforms become tools for bringing individual stories together, fostering connection and reinforcing shared values among activists. Activists actively share knowledge and passion within the community, utilizing various platforms to spread their message beyond specific organizations. Blogs, videos and news interviews serve as records of change, encouraging others to join the cause and actively participate in the collective activism for animal rights.

As the concept of lifestyle activism gains scholarly attention, the intersection between personal choices and activist values becomes evident. Lifestyle activism also shapes and is shaped by the identity of fellow community activists online. Within various activist groups, members actively perform their activism, embodying their values to inspire change. Recordkeeping within activist communities goes beyond documenting activities; it’s a performative act reflecting individual and collective values. Activists navigate various platforms, from Instagram to TikTok, allowing diverse expressions of their activities. The intertwining of individual and collective identities challenges traditional binaries. The personal and collective aspects are enmeshed within the recordkeeping landscape, influencing decisions about what to share, retain, or edit across different platforms.

This section sets the stage for a deeper exploration of emotion, values and their implications on archival appraisal within the broader animal liberation movement. Subsequent chapters will further dissect these aspects, providing insights into the evolving landscape of recordkeeping in the context of narratives, identities, communities and social change.

Conclusion

Direct action, exemplified by live-streamed protests, undercover investigations and short-term disruptions, serves as a dynamic force for animal activists. The utilization of online platforms as digital bundles and emergent community archives reflects the evolution of recordkeeping practices in response to contemporary challenges. The interconnected nature of activist communities, as illustrated through Facebook groups and various online platforms, underscores the significance of digital bundles as containers for community-generated knowledge.

The concept of a digital bundle extends beyond traditional record series, offering a nuanced perspective on recordkeeping in the context of lifestyle activism. Facebook groups, YouTube and other platforms become vital spaces for the creation, dissemination and reshaping of records, showcasing the ongoing evolution of the movement’s narratives. However, this interconnectedness is not without challenges. Repressive measures, exemplified by ag-gag laws, aim to stifle open rescue efforts and hinder the documentation of animal cruelty. Activists face legal barriers, risking fines and imprisonment as they strive to expose the truth.

The struggle against ag-gag laws reflects a broader societal tension between the powerful and those advocating for change. The paranoid style of politics, deeply embedded in legislation, hampers the efforts of animal activists seeking transparency and justice. The historical context of ag-gag laws reveals a complex interplay between activism, societal norms and legislation, underscoring the need for a vigilant approach to recordkeeping as a form of resistance. In the face of legal challenges, activists persist in their commitment to direct action, emphasizing the role of recordkeeping as a tool for societal change. The narrative of open rescue, despite legal repercussions, exemplifies the resilience of activists and their determination to challenge oppressive systems.

In the context of animal activism, open rescue techniques and direct action recordkeeping play a significant role in transnational advocacy. These resource-intensive actions often attract attention from authorities, media and surveillance, generating records that can be used both to support and challenge activist activities. Legal implications, such as potential lawsuits and counter-suits, further underscore the complex dynamics of activist recordkeeping in a transnational context. The use of video documentation not only serves as evidence of ethical concerns but also acts as a tool for countering false narratives perpetuated by opponents, demonstrating the multifaceted nature of modern activist strategies.

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.114; Doherty, Brian, Matthew Paterson and Benjamin Seel. 2002. Direct Action in British Environmentalism. 1st Edition. London: Routledge. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2019. “Connecting Personal and Community Memory-Making: Facebook Groups as Emergent Community Archives.” In Proceedings of RAILS 28-30 November 2018, 24(3):1804. Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia,: Information Research. ↵

- Upward, Frank, Gillian Oliver, Barbara Reed and Joanne Evans. 2017. Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Clayton Vic Australia: Monash University Publishing. ↵

- Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. 2013. “YouTube and the Social Archiving of Intangible Heritage.” New Media & Society, 15 (8): 1259–76. ↵

- Hartley, John, ed. 2011. Digital Futures for Cultural and Media Studies. Hoboken: Wiley. ↵

- Burgess, Jean and Joshua Green. 2013. “Chapter 5: YouTube’s Cultural Politics.” In YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Oxford: Polity. ↵

- Harel, Terri Lee. 2022. “Archives in the making: documenting the January 6 capitol riot on Reddit.” Internet Histories, 6, no. 4, July: 1–21. ↵

- Singer, Peter. 1975. Animal Liberation. New York: Avon Books. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ↵

- McCarthy, John D. and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. ‘Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory’, American Journal of Sociology, 82, no. 6, May: 1213. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.169. ↵

- Ceryes, Caitlin A and Christopher D Heaney. 2019. “Ag-Gag" Laws: Evolution, Resurgence and Public Health Implications.” New Solutions, 28, no. 4, February: 664–682. ↵

- US Congress. 2006. ANIMAL ENTERPRISE TERRORISM ACT 2006, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-109publ374/pdf/PLAW-109publ374.pdf, p.120. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p. 241-3. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p.244. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p.245. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p.245. ↵

- Hofstadter, Richard. 1964. “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Harper’s Magazine, https://harpers.org/archive/1964/11/the-paranoid-style-in-american-politics/. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p.243-4. ↵

- “SURVEILLANCE DEVICES ACT 2016.” AustLII Database, 2016. http://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdb/au/legis/sa/consol_act/sda2016210/. ↵

- Knaus, Christopher. 2022. “Activists Lose Challenge to NSW Laws Banning Secret Filming of Animal Cruelty.” The Guardian, August 10, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/law/2022/aug/10/animal-rights-activists-lose-challenge-to-nsw-laws-banning-secret-filming-of-animal-cruelty. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.141. ↵

- Oppel, Richard. 2013. “Taping of Farm Cruelty Is Becoming the Crime.” The New York Times, April. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/07/us/taping-of-farm-cruelty-is-becoming-the-crime.html. ↵

- ALV. 1993. (Used with permission of rights holder Animal Liberation Victoria) Animal Liberation Victoria magazine ↵

- Hinch, Derryn. 1993.‘The Dungeons of Alpine Poultry’, Hinch, Ten Network, 9 November, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.151. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books. ↵

- Pilkington, Ed. 2015. “Animal rights ‘terrorists’? Legality of industry-friendly law to be challenged.” The Guardian, February. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/feb/19/animal-rights-activists-challenge-federal-terrorism-charges. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p.227. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green is the New Red: An insiders account of a social movement under siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p.227. ↵

- Woodhouse, Aparicio and Zlutnick. 2018. “They Rescued Pigs And Turkeys From Factory Farms - And Now Face Decades In Prison.” The Intercept, December. https://theintercept.com/2018/12/23/dxe-animal-rights-factory-farms/. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.171. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.171. ↵

- Pilkington, Ed. 2015. “Animal rights ‘terrorists’? Legality of industry-friendly law to be challenged.” The Guardian, February. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/feb/19/animal-rights-activists-challenge-federal-terrorism-charges. ↵

- Villanueva, Gonzalo. 2018. A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.162. ↵

- Eastwood, Terry. 1992. “Nailing a Little Jelly to the Wall of Archival Studies.” Archivaria, 35 (Spring): 232–52, p.242. ↵

- Regan, Lauren. 2017. (Used with permission of rights holder CLDC). “Take Yourselves Seriously: Document Retention and Destruction Policies.” Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC). May 26. https://cldc.org/take-yourselves-seriously-document-retention-and-destruction-policies/. ↵

- Regan, Lauren. 2017. “Take Yourselves Seriously: Document Retention and Destruction Policies.” Civil Liberties Defense Center. May 26. https://cldc.org/take-yourselves-seriously-document-retention-and-destruction-policies/. ↵

Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) are complementary frames for addressing societal grand challenges such as social justice imperatives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106). This framing is described here as ‘critical continuum’ research. A community of academics and educators are:

… going beyond the apparent to reveal hidden agendas, concealed inequalities and tacit manipulation (Evans et al., 2017, 2) …

to explore multidimensional accounts of archives and recordkeeping and question societal dynamics for a fairer world. Continuum scholars seek to reveal established power and exclusion in an archival multiverse (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). The archival multiverse is a “plurality of evidentiary texts'' developed by a person, community or group for memory-keeping (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106-7). To ensure equitable societal representation, continuum research progresses analysis of practices beyond narrow and exclusionary archival narratives and systems in institutional and collecting archives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) provide a foundation for exploring societal functions in a multitude of ways and contexts.

References

Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, and Greg Rolan. 2017. “Critical Approaches to Archiving and Recordkeeping in the Continuum.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1 (2): 1–38.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse, and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak 3–7 September 2012.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79–88.

Upward, Frank. 1996. “Structuring the Records Continuum - Part One: Postcustodial Principles and Properties.” Archives and Manuscripts, 24 (2): 268–85.

It is used in this text as a pejorative term to describe large agricultural corporations that wield unethical power over animals as commodities.

"During a typical open rescue, animal activists simply walk onto farms and remove animals showing signs of distress ... Walking onto farms is done openly, without masks, without violence and without property damage."

Scott-Reid, Jessica. 2023. “The Open Rescue Movement for Farm Animals, Explained.” Sentient Food. October 19, 2023. https://sentientmedia.org/open-rescue-movement/.

A term that recognises animals are intelligent sentient beings similar to humans but without the legal acknowledgement of human rights.

Maio, Miriana. 2023. “Why Should We Call Them Non-Human Animals?” International Society of Zooanthropology. May 22, 2023. https://internationalsocietyofzooanthropology.org/en/blog-en/why-should-we-call-them-non-human-animals/.

"The record is always in a process of becoming."

McKemmish, Sue. 1994. “Are Records Ever Actual?” In The Records Continuum: Ian Maclean and Australian Archives First Fifty Years, edited by Sue McKemmish and Michael Piggott, 187–203. Ancora in association with Australian Archives.

The term ‘platform’ is used in this book the way Terri Lee Harel, Muira McCammon and Jessa Lingel refer to them as a discrete but interconnected online space. A digital platform is an online framework or infrastructure that enables the creation, exchange, and consumption of digital content, services, or products. It provides the technological foundation for interactions among users, businesses, and applications, facilitating activities such as communication, commerce, information sharing, and collaboration. Digital platforms often leverage cloud computing, data analytics, and network connectivity to support and enhance these interactions, and can include social media sites, e-commerce marketplaces, content streaming services, and software development environments.

Platforms are also considered here “emergent archival spaces” as defined by Leisa Gibbons.

References

Harel, Terri Lee. 2022. "Archives in the Making: Documenting the January 6 capitol riot on Reddit". Internet Histories, 6(4), 1–21.

McCammon, Muira & Jessa Lingel. 2022. "Situating Dead-and-dying Platforms: Technological failure, infrastructural precarity, and digital decline". Internet Histories, 6(1–2), 1–13.

Gibbons, Leisa. 2020. "Community Archives in Australia: A preliminary investigation. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(4), 1–22.

A group of related records organised because they were created, received, or used during the same activity or function by an individual, organisation, or community.

In the context of networked communities, a digital bundle refers to a cohesive and interconnected collection of records and information shared and distributed across various online platforms and social media channels.

Jennifer Wemwigans uses the term in the context of Indigenous community knowledge and teachings.

Wemwigans, J. 2021. Keynote: Dr. Jennifer Wemigwans – AERI. Presented at the Archival Education and Research Initiative online conference. Online, July 13.

"… collective challenges, based on common purposes and social solidarities, in sustained interaction with elites, opponents, and authorities"

Tarrow, Sidney G. 2011. Power in Movement Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press. p.9.

"... legislation that prohibits covert documentation or investigation of conditions in the farming industry (used chiefly by opponents of such legislation)”.

Oxford University Press. 2019. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/ (accessed 2019)

"Grassroots activism is about mobilizing a group of people, who are passionate about a cause and harnessing the power of their conviction to push for a different outcome. This kind of movement relies on individuals who are willing to drive the change that they are concerned about from the ground up."

Swords, Jojo. 2017. “Grassroots Activism: Make That Change.” Thoughtworks Thailand. November 16, 2017. https://www.thoughtworks.com/en-th/insights/blog/grassroots-activism-make-change.

Non-traditional archives led and managed by communities in spaces such social media.

"Examining emergent community archives and their value to individuals and communities provides an opportunity to explore what Terry Cook refers to as 'ways of imagining archives and archiving' (2013, p. 97) ... a worldview that is not exclusive to the domain of the professional archivist or institutional archives".

Gibbons, Leisa. 2019. “Connecting Personal and Community Memory-Making: Facebook Groups as Emergent Community Archives.” In Proceedings of RAILS 28-30 November 2018, 24(3):1804. Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia.

Lifestyle activists conduct everyday actions in advocating for radical change that are intertwined with their values in disrupting power.

These activists "do not see attention to their lifestyles as separate from their concerns with altering state power and mounting strategic protest. On the contrary, lifestyle practices are heavily politicized..."

Portwood-Stacer, Laura. 2013. Lifestyle Politics and Radical Activism. Bloomsbury Academic.