4 Radical Recordkeeping

Radical recordkeeping is a broad concept for both ways of recording, and part of advocating for change and challenging societal norms. This chapter describes the relationships between archives and radical recordkeeping, with activist tactics to illustrate this concept.

The Radical in Archival Scholarship

The earliest calls for reforming the archive as an institutionally-based construct includes the South African project for Refiguring the Archive to value marginalised voices[1] and Jeanette Bastian’s acknowledgement of community rights to memory in a colonial archive.[2] Andrew Flinn has become the most prolific of writers on community archiving and its principles (including writing on radical archiving with his colleagues[3] to document activism and social movements). That same year, Flinn and Stevens wrote about communities subverting the mainstream and their complex relationships or potential antagonism toward institutions such as archives.[4]

Meanwhile, in Australia, discussions around how Records Continuum Theory and advocating for equitable valuing of personal and societal recordkeeping[5] has developed into an exploration of the term radical recordkeeping. Sue McKemmish’s chapter “Recordkeeping in the Continuum” summarises these developments for a global audience, where the

… theory has framed consideration of disruptive and radical recordkeeping and archival processes … transforming current practices and refiguring archival spaces to be representative of multiple voices and perspectives, thus unsettling the power imbalances embedded in the current records and archives landscape.[6]

Anne Gilliland mirrored this recordkeeping focus in her vision for human-centred radical appraisal and description as a foreground to developing systems that value the ethical functions of archives and activities such as “Acknowledging, Respecting, Enfranchising, Liberating and Protecting … a networked and granularly documented world”.[7] Yet, little has been written about “radical appraisal” apart from describing data collection and retention from mobile devices.[8] The radical practice of appraising, rather than the content itself as radical, is an important distinction.

‘Radical’ has been used in other ways, for example, in describing archivists’ “radical empathy” towards communities to achieve social justice in archives. Analysing power in archival frameworks is a shared critique with those above. Looking at more than legalistic rights-based needs, there are joint aims for the radical to act on the moral codes of the community those records support.[9] Though radical empathy is not from a continuum-based origin, there are lessons from this research for radical recordkeeping: that frameworks too can be built with “radical empathy” toward the social movement. Radical recordkeeping is presented in this book as a way to disrupt the boundaries between archives, archivists and communities requiring this empathy: recognising that the movement can hold power to appraise and manage its own archival narratives.

Unlike much of the existing scholarship that focuses on the appraisal of records related to radical activities or technologies, or on the collection and creation of records to remember past events, this book introduces and explores the concept of radical recordkeeping. This term radical recordkeeping encapsulates the nature of grassroots activist group goals and the radical way they do recordkeeping to support their short-term and long-term aspirations for political and societal transformation.

Transformative Power of Recordkeeping

The radical archival agenda alongside radical recordkeeping can describe how archivists and activist groups can preserve the memory of change, while at the same time progressing transformative new ways of seeing, recording and interacting with the world. Radical narratives through recordkeeping can tell a unique story of grassroots communities that can disrupt archival institutions and traditional mindsets. Discussing digital recordkeeping in disruptive and continuum terms, Terry Cook proposed a better future for the archiving profession by thinking in “an entirely new context” for a socially interconnected world.[10] Similarly, the transformation of current practice and the incorporation of multiple voices exemplifies radical recordkeeping. Radical recordkeeping embraces democratisation and transformation of archives. An example includes records owned, kept and maintained by activists who create them (rather than the archival corpus after creation). Such an approach is a radical affront to collecting tradition, shifting the power from the institution or project team to the citizen archivist.

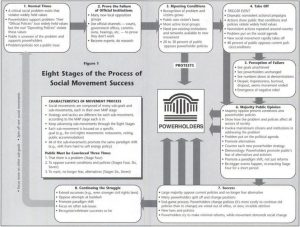

Fig.4.1 The Movement Action Plan Model.[11]

The activist Movement Action Plan model (Figure 4.1) has been used as an analytical tool in the archival literature to visualise a diversity of voices and community goals recorded over time in recursive representation.[12] Success for social movements is not linear or guaranteed, so the contexts and relationships evolving and devolving over time are learned and shared in stages. The strategy and tactics of these groups convey how a multiplicity of voices can combine to achieve an overall paradigm shift in social norms. There is a need for radical transformation of archival infrastructures to achieve these goals.[13] Potential transformation can be achieved by embracing new tools, models and paradigms used by members of grassroots social movements. The radical is not passive but progressive.

Activism in Emergent Community Archives

Leisa Gibbons has explored Facebook groups as emergent community archives[14] and these spaces serve as inspiration and background to understanding radical recordkeeping by an animal activist community. Records continuum researchers in Australia[15] have considered online platforms as another form of record series (therefore, a form of a digital bundle). A bundle or platform as a container suits community contexts since the knowledge represented does not need to mimic a business archive of a traditional recordkeeping structure. Jennifer Wemwigans then used the term digital bundle regarding Indigenous community knowledge and teachings.[16] Acknowledging real-time community archiving on platforms is only in its infancy in the archival literature, but has interdisciplinary reach for YouTube as archive in particular,[17] as a probability archive,[18] accidental archive or living cultural archive[19] at risk of loss. In a recent example, there is recognition of Reddit as an immediate archive and that the longevity of these records is at risk.[20]

Internet as Community Archive

In the 1990s, the digital dark age was considered a phenomenon of the near future.[21] Since then, an easy long-term solution for permanently archiving online content has not been found. The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine with its automated harvesting of websites, seems a promising home for a preserved Internet future – however, there are imperfections in its collection methods.[22] The Wayback Machine, useful for the recovery of expired pages or ‘dead’ websites, also adheres to policies that cause sites to be erased from its index, rendering it an untrustworthy archive that will likely become more unreliable as time goes on, as more domain names expire and more gaps in the machine’s “memory” appear.[23] Vannevar Bush’s idea of the ‘memex’,[24] a desk-sized machine with the knowledge of humanity inside, came to life (with arguably false hope) in the creation of an all-encompassing social archive[25] or “one huge distributed media database”.[26] Web archiving and information technology fields[27] have argued about our ability to ‘keep everything’ digitally as cloud technologies and web crawlers have evolved. However, archivists advocate for more cautious rights-based approaches to ensure that records are controlled, acknowledging the human right to be forgotten[28] and for control of disproportionate personal risks to be mitigated as part of the ongoing appraisal process. Geoffrey Yeo also points to the overabundance of spam and overly ambitious social media archiving projects[29] as examples of why appraisal is not an outdated concept but a complex one in community platforms.

Appraisal and Risk for Online Records

New technology can help disrupt the way we view and apply appraisal in the future.[30] Ed Summers and Ricardo Punzalan are optimistic about scalable computational infrastructures to “make legible the values and ethics that are inscribed in our [appraisal] decisions”.[31] Even before these debates about the capability of mass electronic appraisal began, archivists noted that information would not just sit idly in databases but require assessment at key moments of risk, for example, when migrated into new systems.[32] Frank Upward, too, incorporated Giddens’s view of risk management into recordkeeping as an integrated feature.[33]

In the current setting for appraising web archives, even with both national and state collecting policies, Australia’s web archives are patchy and unequal.

Sometimes one’s decision to collect or not to collect is decided by whether it is technically possible to do so.[34]

Appraisal is already happening in automated ways, but not in ways that equally represent an entire community or animal activists, for example. Community records not harvested by the Wayback Machine (due to the scope of collecting or the complex nature of the site, such as those on social media) face link rot and data loss. Only 30 to 50% of web URLs are accessible after four years, with over 62% not archived.[35] Brewster Kahle estimates that most web pages have an average life of 92 days.[36] Entire social media spaces are at risk, too, since much of the Google+ platform (for example) is now “irretrievably lost”.[37]

Challenges for Activists in Emergent Archival Spaces

Communities and individuals use the emergent archival spaces to foster memory and evidence. Understanding how these communities use complex emergent spaces requires further critical investigation.[38] The ability of platform moderation to mediate, appraise and delete records is an area of discourse to expand.[39] For example, reports of YouTube deleting videos mean that “through a combination of machine learning and human flaggers over eight million videos had been quietly removed from the platform”.[40] Even more concerning is the policing of activists witnessing atrocities posted online.[41] Muira McCammon describes this control as limiting what is seen and who sees it, as anticipatory witnessing by authorities in controlled spaces.[42] In a cloud computing environment, a lack of trust in the authority of platforms reduces user autonomy.[43] In recent years, decentralised open social media platforms have been created in response but are yet to become the norm.[44]

To counter interference or avoid association with recording on corporate or billionaire-owned platforms, values design can be engineered to include user values in cloud infrastructures.[45] This view of adapting infrastructures to balance power in mediated and community recordkeeping platforms online takes a leap beyond “radical user orientation” in archives.[46] There are many differences, but the most significant is recognising ownership and autonomy in the community archiving process and acknowledging the mature recordkeeping in these groups. Some acknowledgements are made in the community archives literature of the need to have “new frameworks” that prioritise community ownership and control in a living archive.[47] However, these attempts have yet to recognise mature processes already inherent to community recordkeeping. Examples of these processes include techniques of forgetting in distributed mobile platforms: since citizen archivists can delete, hide, obscure and selectively edit as an empowered form of appraisal.[48] This is radical recordkeeping. Actors’ patterns of forgetting and use in these emergent spaces can provide new appraisal theories and approaches.[49]

As well as sites of risk to longevity, a critical approach to how these archival spaces wield power helps assess these as tools of potential inequity. Online platforms have been noted as harmful by human rights activists since autonomy is eroded by inequality and abuse by authority online, who seek control of activism and disruptors through the design of these tools.[50] The focus of this book is the way activists use emergent archival spaces, how the appraisal of risks function in terms of longevity, surveillance and autonomy, and how these risks are assessed in radical recordkeeping processes.

Transformative Human-Centred Design

Human-Centered Design (HCD) is the next logical step for discussion here, because it can combine the social power of archives with the community-focused design of new digital technologies. By focusing on and encouraging community involvement and centricity, HCD in recordkeeping systems can foster collective memory and support community growth.

HCD aligns with a sociomaterial approach, which resonates with Records Continuum Theory, actor-network theory, post-phenomenology, postmaterialism and third-wave philosophies. Information systems scholars have had acknowledgement around a linked view of sociomateriality, sociology and technology together with Anthony Giddens’ theories, albeit in the organisational context.[51] Similarly, the HCD literature can offer aligned views toward digital archiving but research on activist social media spaces is scarce.[52] However, research papers on the specific use of Facebook groups[53] have insightful implications for understanding grassroots organising in a network online.

While many HCD concepts are beyond the scope of this book, there are ideas that can be built from common interests across disciplines. Other aligned disciplines to archiving like community informatics and media studies examine technology in societal contexts and expanding the discussions about online appraisal across boundaries of discourse can mean a way forward for understanding radical recordkeeping. How humans perform recordkeeping in their social contexts, for their evidentiary, memory and identity needs, are key to records continuum theorisations. Archival scholars have already begun rethinking how information is organised as multi-relational record sets. Open knowledge graphs like Wikidata[54] (or AI powered ones like Graph-driven RAG solutions.[55]) may overtake alternative archival theorisations of representing identities in communities and events[56] or could potentially be adapted into timeline visualisation[57] of social movements, or considered an interconnected semantic web of all knowledge. Yeo has called for systems of aggregation that reflect

… various “original” orders, different interpretations of context, and other orders newly desired by users.[58]

Gregory Rolan expanded upon the concept of participatory recordkeeping systems design, advocating for interoperability between systems and metadata to facilitate various aspects of record management, including appraisal, control, preservation, retrieval, access and use of records across temporal and spatial boundaries.[59] This approach can extend to communities with distributed rights, by providing them with the tools and infrastructure to determine their own recordkeeping practices.[60]

Personal Recordkeeping Entanglements

The efficacy of a personal archive, its ability to serve as a testament to an individual’s life, hinges upon the systematic approach we take in documenting our experiences and converting them into records. These records, once integrated into the societal archives, become an accessible facet of the collective memory, embodying the experiential wisdom and cultural essence of the community – evidence of our existence in a broader society.[61]

Since McKemmish wrote her seminal work ‘Evidence of Me’[62] personal recordkeeping has been incorporated into social media and platform scholarship. Personal archives analyses have also expanded from only archival literature into the realm of HCD.[63] Some authors in this field recognise the writing of Australian archivists like Adrian Cunningham, who wrote insightfully on personal papers and manuscripts[64] The records continuum has yet to feature in HCI, but the information science literature considers how multiple personal recordkeeping temporalities are embedded in socio-technical systems.[65] Particularly where individuals curate their content by identity needs across multiple platforms,[66] the ability to decide between hardware and cloud archival spaces have been discussed[67] but do not specifically refer to appraisal in this decision-making.

Functions of social media and personal archives include documenting friendship, navigating new media abundance and building cultural capital.[68] Interestingly, for individuals within an activist group, there is one journal article that proposes a values-based appraisal set for individuals collecting sentimental artefacts.[69] Since social movements are not cohesive groups, there can be something to learn from these personal recordkeeping motivations compared to the dominant corporate rationale. However, the investigation into the process of personal recordkeeping itself is not easily observed due to non-standard approaches and ubiquity.[70]

There is the risk of preserving personal records long-term, where individuals have no right to reply on these records in current archiving projects. The report on the Digital Lives Project outlined appraisal parameters relevant to personal archives (related to legal and environmental needs).[71] However, for building participatory archives in institutions, ‘if they build it’ (particularly with imposed parameters) archivists cannot assume that communities will come.[72] Some authors have surveyed the feelings of individuals about the institutional archiving of their personal data from social media,[73] noting the lack of perceived usefulness of personal social media records for long-term retention.

There is a potential next phase of personal recordkeeping that can blend insights from HCD and continuum research. Acker and Brubaker contend that networked social media platforms “can no longer be individuated” due to the multiple relationships and distributed nature of use.[74] A multiverse of records also means a multitude of identities online, creating distributed representations of themselves.[75] There are even more entanglements as artificial intelligence traces merge with personal and group recordkeeping, meaning that the “computer as independent agent will remain blurred”.[76] Nevertheless, for now, humans set up algorithms and the transparency of these decisions (such as recording or deletion) is a new appraisal warrant to consider in systems design.

Linking Across a Multiverse of Communities

Little attention has yet been paid to the “corollary records across corollary moments in the present for liberation from oppressive systems”[77] and across movements. Just as documentation strategy pointed to the interconnections and breadth of records to be apprised beyond the organisational setting to disrupt the dominant voices,[78] there are emergent movements of activist power against commercial interests. Applications of linked open data and peer-to-peer systems, for example, are yet to be discussed in detail in a community archiving context and are often more technical rather than in a way that links these technologies to records continuum capabilities in a multiverse of activism.[79]

For community approaches to distributed archiving, peer-to-peer infrastructure has yet to be a popular method of long-term record storage and has been criticized as “likely to fail” due to: lack of acceptance, likeness to a “Ponzi (pyramid) scheme” and an unsustainable model for preservation, with no long-term benefit for significant short-term investment.[80] There can be skepticism about public good as a significant driver for uptake of peer-to-peer archiving.[81] One exception seems to be the Library of Congress model, which continues its “content stewardship network”.[82] This project has now evolved into an alliance of 267 partnering organisations[83] to support its long-term peer-to-peer archival storage. Distributed knowledge graphs like Wikimedia, which hosts Wikipedia and Wikidata, connect multiple communities in an ambient worldview. The power holders in this scenario still need to be questioned as to who is considered a trusted partner to activists.

Community archival work that operates outside traditional structures requires a rethinking of funding models, labour practices and resource deployment that brings with it questions of political commitment and power.[84]

Suppose monetary investment and commercialisation are drivers for innovation. In that case, there may be a future in archiving technologies driven by distributed ledgers[85] for preserving expensive and ideologically problematic non-fungible tokens. On the ideological flipside, there are also promising applications of linked open data.[86] There are activist-led goals for self-governing decentralised systems that can support the disruption of power-wielding platforms.[87] However, like autonomous driving, implementing human error and lack of foresight can mean a crash. Some technologists have predicted solutions for decentralised web archiving using blockchain.[88] As we see the environmental impacts of the blockchain,[89] any shortsighted fix for a community-focused solution can create a more significant problem if done without a critical eye and activist-led analysis. Technology implemented incorrectly can accelerate existing problems with power imbalance.

The ‘open software’, ‘open research’ and ‘open data’ movements may be slowly changing initially pessimistic views of peer-to-peer development of ‘Ponzi scheme’ shared repositories. This shift is a response to increasingly unwanted institutional and corporate interference in community recordkeeping on corporate platforms.[90] It is yet to be seen if worldwide alliances like that formed by the Library of Congress can be done outside institutional control. Anderson and Allen call this work the ‘Archival Commons’ and link the highly networked environment. It is worth reflecting on the power and socially formed connectivity between records in this literature. However, these ideas of connectivity between institutional records have already been innovated by community practices of linking records online.

From the early ideas of Vannevar Bush to the thoughts of Foucault, linking works and statements together in a web of connectivity to organise and interpret the state of human knowledge has been a key concept at theoretical, philosophical and practical levels.[91] Linked open data and peer-to-peer technologies can bring theory into practice, particularly since the peer-to-peer movement was born originally from piracy, disruption and uprising against dominant power and commercialisation.

Activist Infrastructure Design and Disruption

In the following section, the work of activist Cade Diehm is a source of inspiration for radical recordkeeping infrastructures. His research with The New Design Congress embraces new systems and platform design approaches that disrupt the power dynamic of centralised governance. In the archival context, peer-to-peer networks reflect are early activist infrastructures built to disrupt academia and institutional recordkeeping that prevents the unrestricted use and re-use of information. Diehm describes the “copyright war” as beginning decades before the launch of Napster, the audio file-sharing platform declared illegal for breaching copyright laws. As an alternative to centralised governance, communities can share a resilient configuration of software and protocols whilst avoiding ownership by a single authority.

The internet itself is a decentralised network … Who are these peer-to-peer communities? They are developers, designers and early adopters.[92]

Given the early innovation for illegal file sharing, activist communities can be considered at the bleeding edge of creativity and archival solutions before institutional attempts to replicate these technologies can be proposed, staffed, funded and implemented. About a decade after Napster emerged, the Stanford University Library launched LOCKSS (the Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe initiative). LOCKSS has been renamed the CLOCKSS project (see chapter seven) and continues. In comparison, because of its illegality, Napster no longer exists. However, the philosophy of open access to scientific publications has sustained more momentum in the ‘pirating’ of scientific journals (for example, in SciHub) due to the belief that information activists should aid publication sharing in the public domain and knowledge not be hidden behind a paywall. SciHub is argued to be in the public interest. Since its indictment for breaching copyright law back in 2015, the ability of SciHub to avoid the suppression of what Quirin Schiermeier calls a game of “hide and seek with publishers”[93] continually creates new website domain addresses for this content. SciHub is still locatable in 2022 via a website dedicated to sharing SciHub links.[94] SciHub can be likened to the David vs Goliath story – the citizen actors versus the commercial interests of academic publishing.

Often – but not always – decentralised networks emerge due to a collective desire to rebalance societal power. One of the antagonisms that brought these tensions to the boiling point was the series of legal battles over digital intellectual property rights.[95]

SciHub disrupts the power of the institutional publishers and peer-to-peer archiving has been implemented by blending activists’ and archivists’ roles.[96] Here the radical recordkeeping of Redditors has created a grassroots peer-to-peer archiving project of SciHub called “SciHub P2P”.[97] The principle of open knowledge brings these peer-to-peer activists together. On these activist systems designers:

Their politics are diverse, yet there are areas of consensus. They rally around the values of self expression, alternative data governance, censorship resistance and interoperability. Their communities organise, debate and signal politics through their respective networks, encoding protest in encryption, or framing servers as facilitators of self-expression.[98]

Decentralised activist networks and peer-to-peer communities can potentially disrupt power differentials. Rather than participating in archival infrastructures, they lead their own spaces with embedded politics, power and governance with self-determination. With the expanded activist peer community, there is the ability to connect with people who have diverse politics and views. The values of each activist group are a combined driver to form an activist architecture. However, the longevity of peer-to-peer architecture is a concern.

How precarious are decentralised networks? Answering this requires an understanding of both the power of their political energy and history of antagonism.[99]

There is an opportunity to build on decentralised networked archives and the aligned decolonise design, cypherphunk and cyberlibertarian movements. There is a push to rethink existing systems design and connect archival disruption to the work of activist programmers and libertarians known for promoting platform commons. The drive for decentralised community-led power online is not new and has a fifteen-year buildup of dissent.[100] It is what the founder of the disruptive Telegram platform (built [arguably] for the goal of decentralization, balance and equality) calls the “… the most important battle of our generation”.[101] There is a potential shift to democratised or investigating peer-to-peer power in technologies. For example, in democratising financial markets using new platforms like Robinhood, activist traders caused a squeeze on the share market in the Gamestop saga of 2021.[102] In response, Robinhood started restricting its use by the “Reddit Rebellion” buyers.[103] Despite the promising uprising, the Robinhood platform rebuked its name and shut down the grassroots disruption to enforce the economic status quo. Rethinking platforms and their control is part of a broader cyberlibertarian movement as activists fight back against the microaggressions built into and used by powerful actors and institutions.

Supporters of open software, like The New Design Congress advocate for decentralised systems and infrastructures to better represent their communities and avoid erosion of their privacy and autonomy. Networked communities interested in the semantic web and its moderation have born anti-surveillance movements[104] and privacy advocates with varied calls to action in online recordkeeping[105] with the knowledge that “centralised platforms crave data collection and thirst for trust from the communities they seek to exploit …”.[106]

Trusted activists in open platform design implement new applications with user security and privacy as the primary goal. In response to the predatory nature of social media and commercial platforms, open-source and distributed systems affront data harvesting business models. The Signal application, for example, is designed so that the community has contact details for activist organising, but in case a phone is confiscated by an adversary – a bot is an intermediary to prevent anyone from having private phone numbers; they can only see ‘the bots’ number.[107]

Conclusion

From the theoretical underpinnings rooted in archival scholarship to the practical implications observed in emergent community archives and digital platforms, the journey through this chapter has illuminated the multifaceted nature of radical recordkeeping and its significance in challenging societal norms and power structures. Radical recordkeeping represents a paradigm shift in how we conceptualise, create and manage records. It disrupts traditional notions of archival authority and ownership, empowering grassroots communities to reclaim agency over their narratives and histories. By foregrounding principles of inclusivity, equity and autonomy, radical recordkeeping fosters a more democratic and representative archival landscape, one that reflects the diversity of voices and experiences within society.

The theoretical frameworks of Records Continuum Theory, human-centered design and sociomateriality have provided valuable lenses through which to understand and analyze the complexities of radical recordkeeping. From the concept of digital bundles to the role of personal recordkeeping entanglements, these frameworks offer a holistic view of recordkeeping practices in the digital age, highlighting the interconnectedness between technology, society and culture. The exploration of emergent archival spaces, such as online platforms and peer-to-peer networks, underscores the importance of adaptability and resilience in archival infrastructures. As activists and activist archivists navigate the challenges of data preservation, platform moderation and surveillance, there are possible new paths towards decentralised and community-led approaches to recordkeeping. These efforts not only challenge dominant power structures but also embody the values of self-expression, censorship resistance and community-centric interoperability.

- Hamilton, Carolyn, Verne Harris, Jane Taylor, Michele Pickover, Graeme Reid and Razia Saleh, eds. 2002. Refiguring the Archive. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. ↵

- Bastian, Jeannette Allis. 2003. “Chapter 1: A Community of Records.” In Owning Memory How a Caribbean Community Lost Its Archives and Found Its History, 1–18. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited. ↵

- Flinn, Andrew, Mary Stevens and Elizabeth Shepherd. 2009. “Whose Memories, Whose Archives? Independent Community Archives, Autonomy and the Mainstream.” Archival Science, 9 (1–2): 71–86. ↵

- Flinn, Andrew and Mary Stevens. 2009. “‘It Is Noh Mistri, Wi Mekin Histri.’ Telling Our Own Story: Independent and Community Archives in the UK, Challenging and Subverting the Mainstream.” In Community Archives: The Shaping of Memory, edited by Jeannette A Bastian and Ben Alexander. United Kingdom: Facet Publishing. ↵

- McKemmish, Sue. 1996 “Evidence of me .” Archives & Manuscripts 24, no.1; Pollard, Riva A. 2001. “The Appraisal of Personal Papers: A Critical Literature Review.” Archivaria, 52 (February): 136–50. ↵

- McKemmish, Sue. 2017. “Chapter 4: Recordkeeping in the Continuum. An Australian Tradition.” In Research in the Archival Multiverse, edited by Anne Gilliland, Sue McKemmish, and Andrew Lau, 122 – 160. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: Monash University Publishing, p.125. ↵

- Gilliland, Anne J. 2014. “Reconceptualizing Records, the Archive and Archival Roles and Requirements in a Networked Society.” Book Science. Knygotyra (63): 17–34, p.31. ↵

- Acker, Amelia. 2015. “Radical appraisal practices and the mobile forensic imaginary.” Archive Journal, 5, no. 1. ↵

- Caswell, Michelle and Marika Cifor. 2016. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives.” Archivaria, 81 (Spring): 23–43. ↵

- Terry Cook, 2010 quoted by Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, Elizabeth Daniels and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Self-determination and archival autonomy: advocating activism.” Archival Science, 15, no. 4, December: 337–368, p.359). ↵

- Moyer, Bill. 2001. (Used with permission) Doing Democracy : The MAP Model for Organising Social Movements. Philadelphia: New Society ↵

- Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, Elizabeth Daniels and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Self-determination and archival autonomy: advocating activism.” Archival Science, 15, no. 4, December: 337–368, p.359. ↵

- Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, Elizabeth Daniels and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Self-determination and archival autonomy: advocating activism.” Archival Science, 15, no. 4, December: 337–368, p.355. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2019. “Connecting Personal and Community Memory-Making: Facebook Groups as Emergent Community Archives.” In Proceedings of RAILS, 28-30 November 2018, 24(3):1804. Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia,: Information Research. ↵

- Upward, Frank, Gillian Oliver, Barbara Reed and Joanne Evans. 2017. Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Clayton Vic Australia: Monash University Publishing. ↵

- Wemwigans, Jennifer. 2021. “Keynote: A Digital Bundle” at the Archival Education and Research Institutes, July 13. ↵

- Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. 2013. “YouTube and the Social Archiving of Intangible Heritage.” New Media & Society, 15 (8): 1259–76. ↵

- Hartley, John, ed. 2011. Digital Futures for Cultural and Media Studies. Hoboken: Wiley. ↵

- Burgess, Jean, and Joshua Green. 2013. “Chapter 5: YouTube’s Cultural Politics.” In YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Oxford: Polity. ↵

- Harel, Terri Lee. 2022. “Archives in the making: documenting the January 6 capitol riot on Reddit.” Internet Histories, 6, no. 4, July: 1–21. ↵

- Kuny, Terry. 1997. “A Digital Dark Ages? Challenges in the Preservation of Electronic Information.” In Workshop: Audiovisual and Multimedia Joint with Preservation and Conservation, Information Technology, Library Buildings and Equipment, and the PAC Core Programme. IFLA. ↵

- Diehm, Cade and Benjamin Royer. 2022. “Web Preservation In The Polycrisis.” New Design Congress. ↵

- De Kosnik, Abigail. 2016. Rogue Archives. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, p.50. ↵

- Bush, Vennevar. 1945. “As We May Think.” The Atlantic, July. ↵

- De Kosnik, Abigail. 2016. Rogue Archives. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, p.41. ↵

- Manovich, Lev. 2002. “The Language of New Media.” Canadian Journal of Communication, 27 (1). ↵

- e.g. Nelson, Michael L, Frank McCown, Joan A Smith and Martin Klein. 2007. “Using the web infrastructure to preserve web pages.” International Journal on Digital Libraries, 6, no. 4, July: 327–349; Rosenthal, David. 2012. “Lets Just Keep Everything Forever In The Cloud.” DSHR’s Blog, May; Barclay, Blair. 2015. “...Keep everything?” LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-we-moving-worldwhere-keep-everything-forever-barclay-t-blair ↵

- Black, Shelly. 2020. “The implications of digital collection takedown requests on archival appraisal.” Archival Science, 20, no. 1, March: 91–101; Carbone, Kathy, Anne J Gilliland, Antonina Lewis, Sue McKemmish and Gregory Rolan. 2021. “Towards a human right in recordkeeping and archives.” In Diversity, Divergence, Dialogue: 16th International Conference, iConference, Beijing, China, March 17–31, 2021, Proceedings, Part II, edited by Katharina Toeppe, Hui Yan and Samuel Kai Wah Chu, 12646:285–300. Lecture notes in computer science. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ↵

- Yeo, Geoffrey. 2018. “Chapter 4: Can We Keep Everything? The future of appraisal in a world of digital profusion.” In Archival Futures. Edited by Caroline Brown. London: Facet Publishing, p.55. ↵

- Yeo, Geoffrey. 2018. “Chapter 4: Can We Keep Everything? The future of appraisal in a world of digital profusion.” In Archival Futures, edited by Caroline Brown. London: Facet Publishing, p.55; Gilliland, Anne. 2014. “Archival Appraisal: Practising on Shifting Sands.” In Archives and Recordkeeping : Theory into Practice, 31–62. London: Facet Publishing. ↵

- Summers, Ed and Ricardo Punzalan. “Bots, seeds and people: web archives as infrastructure.” In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing - CSCW' ’17, 821–834. New York, USA: ACM Press, p.11. ↵

- Bearman, David A. 2006. “Moments of Risk: Identifying Threats to Electronic Records.” Archivaria, 62, no. Fall. ↵

- Upward, Frank. 1997. “Structuring the records continuum (Series of two parts) Part 2: Structuration theory and recordkeeping.” Archives and Manuscripts, 25, no. 1, May: 10–35, p.19. ↵

- Earl, Jennifer, Thomas V Maher and Jennifer Pan. 2022. “The Digital Repression of Social Movements, Protest and Activism: A Synthetic Review.” Science Advances, 8 (10), pp.33 & 35. ↵

- Król, Karol and Dariusz Zdonek. 2019. “Peculiarity of the bit rot and link rot phenomena.” Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 69, no. 1/2, October: 20–37, p.23. ↵

- Carlson, Frank. 2017. “Internet history is fragile. This archive is making sure it doesn’t disappear”, PBS NewsHour, January. ↵

- Król, Karol and Dariusz Zdonek. 2019. “Peculiarity of the bit rot and link rot phenomena.” Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 69, no. 1/2, October: 20–37, p.29. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2020. “Community archives in Australia: A preliminary investigation.” Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69, no. 4, November: 1–22. ↵

- Acker, Amelia. 2015. “Radical appraisal practices and the mobile forensic imaginary.” Archive Journal 5, no. ↵

- Hills, Megan C. 2018. “YouTube Has Quietly Removed Over 8 Million Videos While You Weren’t Looking.” Forbes. April. ↵

- Hepburn, Katharine. 2013. “Introduction.” In Mediation and protest movements, edited by B Cammaerts, Alice Mattoni and Patrick McCurdy. 3 – 19. Bristol: Intellect; Human Rights Center. 2021. “Digital Lockers: Archiving Social Media Evidence of Atrocity Crime.” UC Berkeley School of Law, p.2-3. ↵

- McCammon, Muira. 2020. “Anticipatory witnessing: military bases and the politics of pre-empting access.” Information, Communication & Society, 25, no. 7, September: 1–17. ↵

- Verkerk, Jane. 2021. “Cloud computing as Digital Imaginary. A critical making approach to user perceptions and experiences,” April, p.34. ↵

- Oxborrow, Ian and Alvin R Cabral. 2022. “What Is Mastodon? Twitter Users Are Switching Social Network.” The National, November 7. ↵

- Verkerk, Jane. 2021. “Cloud computing as Digital Imaginary. A critical making approach to user perceptions and experiences,” April, p.34. ↵

- Huvila, Isto. 2008. “Participatory archive: towards decentralised curation, radical user orientation, and broader contextualisation of records management.” Archival Science, 8, no. 1: 15–36. ↵

- Stevens, Mary, Andrew Flinn and Elizabeth Shepherd. 2010. “New frameworks for community engagement in the archive sector: from handing over to handing on.” International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16, no. 1–2, January: 59–76. ↵

- Acker, Amelia. 2015. “Radical appraisal practices and the mobile forensic imaginary.” Archive Journal, 5, no. 1, p.8-9. ↵

- Acker, Amelia. 2015. “Radical appraisal practices and the mobile forensic imaginary.” Archive Journal, 5, no. 1. ↵

- Argüelles, Alexandra. 2022. “Technosolutionism as Obstruction of Justice.” In Digital Violence in Mexico: The State vs. Civil Society, edited by Alexandra Argüelles, English Edition, 157–183. Mexico: comun.al, Malpaís Ediciones, p.182. ↵

- Orlikowski, Wanda J. and Susan V. Scott. 2008. “Sociomateriality: Challenging the Separation of Technology, Work and Organization.” The Academy of Management Annals, 2 (1): 433–474. ↵

- Velte, Ashlyn. 2018. “Ethical challenges and current practices in activist social media archives.” The American Archivist, 81, no. 1 March: 112–134, p.112. ↵

- Stuckey, Helen, Melanie Swalwell, Angela Ndalianis and Denise de Vries. 2013. “Remembrance of games past: The popular memory archive.” In Proceedings of The 9th Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment Matters of Life and Death - IE ’13, 1–7. New York, USA: ACM Press; Gibbons, Leisa. 2019. “Connecting Personal and Community Memory-Making: Facebook Groups as Emergent Community Archives.” In Proceedings of RAILS 28-30 November 2018, 24(3):1804. Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia,: Information Research. ↵

- See https://m.wikidata.org/wiki/Wikidata:Main_Page, ↵

-

Iantosca, Michael. 2024. “Understanding the Future of Knowledge Graph-Driven Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG).” Mediaum. October 13, 2024. https://medium.com/@nc_mike/understanding-the-future-of-knowledge-graph-driven-retrieval-augmented-generation-rag-84f900f80042.↵

- Niu, Jinfang. 2015. “Event-based archival information organization.” Archival Science, 15, no. 3, September: 315–328. ↵

- Anderson, Scott and Robert Allen. 2009. “Envisioning the archival commons.” The American Archivist, 72, no. 2, September: 383–400; Lemieux, Victoria L. 2015. “Visual analytics, cognition and archival arrangement and description: studying archivists’ cognitive tasks to leverage visual thinking for a sustainable archival future.” Archival Science, 15, no. 1, March: 25–49. ↵

- Yeo, Geoffrey. 2012. “Bringing things together: Aggregate records in a digital age.” Archivaria, 74, no. November: 43–91, p.44. ↵

- Rolan, Gregory. 2017. “Towards interoperable recordkeeping systems: A meta-model for recordkeeping metadata.” Records Management Journal, 27, no. 2, July: 125–148. ↵

- Rolan, Gregory, Sue McKemmish, Gillian Oliver, Joanne Evans and Shannon Faulkhead. 2020. “Digital equity through data sovereignty: A vision for sustaining humanity.” iConference, Boras, Sweden. ↵

- McKemmish, Sue. 1996. “Evidence of me.” Archives & Manuscripts, 24, no. 1: 28–45. ↵

- McKemmish, Sue. 1996. “Evidence of me.” Archives & Manuscripts, 24, no. 1: 28–45. ↵

- Marshall, Catherine C., Sara Bly and Francoise Brun-Cottan. 2007. “The Long Term Fate of Our Digital Belongings: Toward a Service Model for Personal Archives.” ArXiv, April; Kirk, David S. and Abigail Sellen. 2010. “On Human Remains.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 17 (3): 1–43; Marshall, Catherine C. and Frank M. Shipman. 2012. “On the Institutional Archiving of Social Media.” In Proceedings of the 12th ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries - JCDL ’12, 1. New York, USA: ACM Press; Odom, William, Abi Sellen, Richard Harper and Eno Thereska. 2012. “Lost in Translation: Understanding the Possession of Digital Things in the Cloud.” In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’12, 781. New York, USA: ACM Press; Lindley, Siân E., Catherine C. Marshall, Richard Banks, Abigail Sellen and Tim Regan. 2013. “Rethinking the Web as a Personal Archive.” In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web - WWW ’13, 749–60. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press; Zhao, Xuan and Siân E Lindley. “Curation through use.” In Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI' ’14, 2431 –2440. New York, USA: ACM Press, 2014; Gulotta, Rebecca, William Odom, Jodi Forlizzi and Haakon Faste. 2013. “Digital Artifacts as Legacy: Exploring the Lifespan and Value of Digital Data.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’13, 1813–22. New York, USA: ACM Press; McKenzie, Pamela J. and Elisabeth Davies. 2022. “Documenting Multiple Temporalities.” Journal Distilasi, 78 (1): 38–59. ↵

- Cunningham, Adrian. 1994. “The archival management of personal records in electronic form: some suggestions.” Archives and Manuscripts, 22, no. 1, May: 94–105; Cunningham, Adrian. 1996. “Beyond the Pale? The ‘flinty’ relationship between archivists who collect the private records of individuals and the rest of the archival profession in Australia.” In Australian Society of Archivists, edited by Collecting Archives Special Interest Group. The Provenance Electronic Magazine, Vol.1 No.2, 1996. ↵

- McKenzie, Pamela J and Elisabeth Davies. 2022. “Documenting multiple temporalities.” Journal Distilasi, 78, no. 1, January: 38–59. ↵

- Gulotta, Rebecca, William Odom, Jodi Forlizzi and Haakon Faste. 2013. “Digital artifacts as legacy: Exploring the lifespan and value of digital data.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’13, 1813–1822. New York, USA: ACM Press. ↵

- Odom, William, Abi Sellen, Richard Harper and Eno Thereska. 2012. “Lost in translation: Understanding the possession of digital things in the cloud.” In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’12, 781. New York, USA: ACM Press; Zhao, Xuan and Siân E Lindley. 2014. “Curation through use.” In Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI ’14, 2431 – 2440. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. ↵

- Good, Katie Day. 2013. “From scrapbook to Facebook: A history of personal media assemblage and archives.” New Media & Society, 15, no. 4, June: 557–573, p.557. ↵

- Kirk, David S and Abigail Sellen. 2010. “On human remains.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 17, no. 3, July: 1–43. ↵

- Trace, Ciaran B and Luis Francisco-Revilla. 2015. “The value and complexity of collection arrangement for evidentiary work.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66, no. 9,September: 1857–1882; Wang, Yang and Sun Sun Lim. 2021. “Nomadic Life Archiving across Platforms: Hyperlinked Storage and Compartmentalized Sharing.” New Media & Society, 23 (4): 796–815. ↵

- John, JL, J Rowlands, I Willaims and K Dean. 2010. “Digital lives: personal digital archives for the 21st century: an initial synthesis .” Digital Lives Research Paper. British Library, February 22. ↵

- Eveleigh, Alexandra. 2012. “Welcoming the World: An Exploration of Participatory Archives.” International Council on Archives Brisbane, Australia. Brisbane, Australia: ICA, p.4. ↵

- Condron, Melody. 2019. “Identifying individual and institutional motivations in personal digital archiving.” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture, 48, no. 1, March: 28–37; Marshall, Catherine C and Frank M Shipman. 2014. “An argument for archiving Facebook as a heterogeneous personal store.” In IEEE/ACM Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, 11–20. IEEE. ↵

- Acker, Amelia and Jed R Brubaker. 2014. “Death, memorialization, and social media: A platform perspective for personal archives.” Archivaria, 77, no. Spring: 1–23, p.7. ↵

- Baumer, Eric PS and Jed R Brubaker. 2017. “Post-userism.” In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 6291 - 6303. New York, USA: ACM, p.6297. ↵

- Yeo, Geoffrey. 2018. “Representation, performativity and social action: why records are not (just) information.” In Records, information and data: exploring the role of record keeping in an information culture, 129–162. Facet, p.144. ↵

- Caswell, Michelle. 2021. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group. ↵

- Samuels, Helen. 1998. Varsity Letters : Documenting Modern Colleges and Universities. Chicago: Scarecrow Press. ↵

- A recent non-technical example that points to the potential of AI to standardise metadata to aid in the power of linked data, is: Zou, Qing, and Eun G. Park. 2024. “Archival Context, Provenance, and a Tool to Capture Archival Context”. Archival Science, 24 (4): 801–24. ↵

- Nelson, Michael L, Frank McCown, Joan A Smith and Martin Klein. 2007. “Using the web infrastructure to preserve web pages.” International Journal on Digital Libraries, 6, no. 4, July: 327–349, p.334. ↵

- Nelson, Michael L, Frank McCown, Joan A Smith and Martin Klein. 2007. “Using the web infrastructure to preserve web pages.” International Journal on Digital Libraries, 6, no. 4, July: 327–349. ↵

- Churchill, Elizabeth and Jeff Ubois. 2008. “Designing for digital archives.” Interactions, 15, no. 2, March: 10–13., p.13. ↵

- NDSA. “About the NDSA.” National Digital Stewardship Alliance, 2022. ↵

- Wood, Stacy. 2019. “Crowdfunding and the moral economies of community archival work.” In Participatory Archives, 131–142. Cambridge: Facet, p.139. ↵

- Kelley, Mike. 2021. “Will Your NFT Art Live Forever? .” The Block Magazine, May. ↵

- Gracy, Karen F. “Archival description and linked data: a preliminary study of opportunities and implementation challenges.” Archival Science 15, no. 3 (September 2015): 239–294. ↵

- Platt, Moritz and Peter McBurney. 2021. “Self-Governing Public Decentralised Systems: Work in Progress.” In Socio-Technical Aspects in Security and Trust: 10th International Workshop, STAST 2020, Virtual Event, September 14, Revised Selected Papers, edited by Thomas Groß and Luca Viganò, 12812:154–167. Lecture notes in computer science. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ↵

- e.g. Platt, Moritz and Peter McBurney. 2021. “Self-Governing Public Decentralised Systems: Work in Progress.” In Socio-Technical Aspects in Security and Trust: 10th International Workshop, STAST 2020, Virtual Event, September 14, 2020, Revised Selected Papers, edited by Thomas Groß and Luca Viganò, 12812:154–167. Lecture notes in computer science. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ↵

- Schinckus, Christophe. 2020. “The good, the bad and the ugly: An overview of the sustainability of blockchain technology.” Energy Research & Social Science, 69, November: 101614. ↵

- Saber, Dima, Natalie Cadranel, Friedhelm Weinberg and Iván Martínez. 2020. “Recordkeepers of the resistance: do you trust the dark force to save your activist history?” RightsCon 2020. ↵

- Anderson, Scott and Robert Allen. 2009. “Envisioning the archival commons.” The American Archivist, 72, no. 2, September: 383–400, p.389. ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

- Schiermeier, Quirin. 2015. “Pirate research-paper sites play hide-and-seek with publishers.” Nature, December. ↵

- See https://sci-hub-links.com/ ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

- Gault, Matthew. 2019. “Archivists Are Trying to Make Sure a ‘Pirate Bay of Science’ Never Goes Down.” Vice, December. ↵

- “Introduction - Sci-Hub on P2P.” 2021. GitHub. https://sci-hub-p2p.readthedocs.io/_en/introduction.html. ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

- Durov, Pavel. 2020. “What Was TON And Why It Is Over.” Telegraph, May. ↵

- Kelleher, Dennis M, Jason Grimes and Andres Chovil. 2022. “Securities - Democratizing Equity Markets with and without Exploitation: Robinhood, Gamestop, Hedge Funds, Gamification,High Frequency Trading and More.” Western New England Law Review, 44 (51). ↵

- Kelleher, Dennis M, Jason Grimes and Andres Chovil. 2022. “Securities - Democratizing Equity Markets with and without Exploitation: Robinhood, Gamestop, Hedge Funds, Gamification, High Frequency Trading, and More.” Western New England Law Review, 44 (51). ↵

- Assange, Julian, Jacob Appelbaum, Andy Müller-Maguhn and Jérémie Zimmermann. 2012. Cypherpunks : freedom and the future of the internet. OR Books. ↵

- Mantegna, Micaela. 2022. “Every breath you take, every move you make: Neurotechnology, XR and the metaverse of surveillance.” AccessNow. ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

- Diehm, Cade. 2020. “This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network.” The New Design Congress, July. ↵

In using the word ‘radical’, it is essential not to be ‘othering’ activists but to value and define their political agenda in a way that respects their nuanced identities and indicates transcendence of everyday norms. This term is open to development and reinterpretation. As Andrew Flinn has noted,

… it is important not to get too distracted by definitional exactitude. Often these definitions can confuse as much as they clarify, and exclude as much as they include … many individuals working on community projects will not recognise these as community archives at all (2011, 153).

Flinn, Andrew. 2011. “Archival Activism: Independent and Community-Led Archives, Radical Public History and the Heritage Professions.” InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, May.

Definitions, then, are sometimes dynamic, and the original formation of a term is the first step. The chosen social movement for this study is narrowed in scope to understand only one activist context to the exclusion of others. Still, it delves into one case in the hope that this research could be a valuable model for other groups in the future.

"… disruption of traditional recordkeeping paradigms in revolutionary or profound ways by groups and recordkeeping and archiving professionals who challenge or disrupt social or mainstream norms."

Jarvie, Katherine, Greg Rolan, and Heather Soyka. 2017. “Why ‘Radical Recordkeeping’?” Archives and Manuscripts, 45 (3): 173–75, p.173.

"Grassroots activism is about mobilizing a group of people, who are passionate about a cause and harnessing the power of their conviction to push for a different outcome. This kind of movement relies on individuals who are willing to drive the change that they are concerned about from the ground up."

Swords, Jojo. 2017. “Grassroots Activism: Make That Change.” Thoughtworks Thailand. November 16, 2017. https://www.thoughtworks.com/en-th/insights/blog/grassroots-activism-make-change.

To deconstruct and reframe the power of control into the hands of the archivally oppressed subject.

McKemmish, Sue. 2017. “Chapter 4: Recordkeeping in the Continuum. An Australian Tradition.” In Research in the Archival Multiverse , edited by Anne Gilliland, Sue McKemmish, and Andrew Lau, 122 – 160. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: Monash University Publishing, p.154.

Non-traditional archives led and managed by communities in spaces such social media.

"Examining emergent community archives and their value to individuals and communities provides an opportunity to explore what Terry Cook refers to as 'ways of imagining archives and archiving' (2013, p. 97) ... a worldview that is not exclusive to the domain of the professional archivist or institutional archives".

Gibbons, Leisa. 2019. “Connecting Personal and Community Memory-Making: Facebook Groups as Emergent Community Archives.” In Proceedings of RAILS 28-30 November 2018, 24(3):1804. Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia.

Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) are complementary frames for addressing societal grand challenges such as social justice imperatives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106). This framing is described here as ‘critical continuum’ research. A community of academics and educators are:

… going beyond the apparent to reveal hidden agendas, concealed inequalities and tacit manipulation (Evans et al., 2017, 2) …

to explore multidimensional accounts of archives and recordkeeping and question societal dynamics for a fairer world. Continuum scholars seek to reveal established power and exclusion in an archival multiverse (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). The archival multiverse is a “plurality of evidentiary texts'' developed by a person, community or group for memory-keeping (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106-7). To ensure equitable societal representation, continuum research progresses analysis of practices beyond narrow and exclusionary archival narratives and systems in institutional and collecting archives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) provide a foundation for exploring societal functions in a multitude of ways and contexts.

References

Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, and Greg Rolan. 2017. “Critical Approaches to Archiving and Recordkeeping in the Continuum.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1 (2): 1–38.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse, and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak 3–7 September 2012.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79–88.

Upward, Frank. 1996. “Structuring the Records Continuum - Part One: Postcustodial Principles and Properties.” Archives and Manuscripts, 24 (2): 268–85.

A group of related records organised because they were created, received, or used during the same activity or function by an individual, organisation, or community.

In the context of networked communities, a digital bundle refers to a cohesive and interconnected collection of records and information shared and distributed across various online platforms and social media channels.

Jennifer Wemwigans uses the term in the context of Indigenous community knowledge and teachings.

Wemwigans, J. 2021. Keynote: Dr. Jennifer Wemigwans – AERI. Presented at the Archival Education and Research Initiative online conference. Online, July 13.

Muira McCammon describes this control as limiting what is seen and who sees it, by authorities in controlled spaces. Here the idea is expanded to a definition for distrust of surveillance online.

McCammon, Muira. “Anticipatory witnessing: military bases and the politics of pre-empting access.” Information, Communication & Society, 25, no. 7 (September 2020): 1–17.

"Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a method used to enhance the generation of responses by retrieving relevant information from a dataset before generating an answer. Instead of relying on pre-trained data alone, RAG uses retrieved context to ensure that answers are accurate, timely, and relevant.

In a GraphRAG framework, RAG pulls data from graph databases, using the relationships between nodes to create context-aware, relevant responses. For instance, if a user queries a product’s performance history, the system can locate not only the product’s specifications but also its sales history, customer feedback, and similar products."

“GraphRAG: Definition, Approaches, and Examples .” 2024. Lettria. November 8, 2024. https://www.lettria.com/blogpost/graphrag-definition-approaches-and-examples.

Users of the community platform Reddit

Decolonising design means putting Indigenous first; dismantling tech bias and racist bias; making amends through more

than diversity, equity, and inclusion; and reprioritising existing resources to decolonise.

Tunstall, Elizabeth. 2023. Decolonizing Design : A Cultural Justice Guidebook. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England: The MIT Press.

"Cypherpunk refers to social movements, individuals, institutions, technologies, and political actions that, with a decentralised approach, defend, support, offer, code, or rely on strong encryption systems in order to re-shape social, political, or economic asymmetries."

Ramiro, André, and Ruy de Queiroz. 2022. “Cypherpunk.” Internet Policy Review 11 (2).

"Cyberlibertarianism or technolibertarianism is a political philosophy. Like libertarianism in general, it advocates liberty as the main organizing principle of social, political and economic life. The specificity of cyberlibertarianism is its belief in the liberating role of technology, especially the Internet. It proposes to solve the problems of society, economics and politics by maximizing the freedom of actors on the Internet and their voluntary cooperation, and minimizing the influence of state coercion."

Soos, Gábor. 2018. “Smart Decentralization? The Radical Anti-Establishment Worldview of Blockchain Initiatives.” Smart Citities and Regional Development (SCRD) Journal 2 (2): 35–49.