1 A Critical Approach to a Wicked Problem

This book captures the essence of eight-year research study[1] on an animal activist group and records continuum archivists to provide some practical advice to redressing the gaps in archival institutional memory. Approaching the problem from the view of respecting the actions of activists themselves, rather than relying on post-hoc collecting by archival institutions is the crux of future-forward documenting (rather than reactive collecting). The study approaches this problem from the perspective of respecting radical recordkeeping and the actions of activists, rather than relying on post-hoc collecting by archival institutions. It emphasises that future-oriented documentation should not just be reactive collecting but should engage actively with Records Continuum Theory.

The focus of this book is to enhance engagement with continue-based tools, templates and ideas within this text, to be adapted, owned and shaped by new communities to make them appropriate and timely for their needs. Digital records of activists bear witness to the stories of social change. These vital accounts, often on online platforms, face the risk of obfuscation or deletion by the cloud storage owners that host them. As faith in traditional media to represent an unbiased truth, the need for a resilient, coherent and reliable archive that can preserve the authentic voice of grassroots, geographically dispersed and networked communities has never been more pressing. This book embarks on an exploration of the emergent concept of radical recordkeeping, a term that describes how activists and archivists use records and digital infrastructures to disrupt established norms. These norms, perpetually marginalizing the activist voice, underscore the urgency for a paradigm shift in archival practices – moving beyond the preoccupation with collecting records after events occur and embracing the active, ongoing and dynamic nature of social movements.

Drawing from research on how activists memorialise, remember, forget and appraise their records online,[2] this book explores what has elsewhere been described as participatory appraisal While posited as a solution to inequitable archival practices, participatory appraisal remains a largely unexplored area.

A Basis in Records Continuum Theory

Through the lens of Records Continuum Theory, each chapter of this book leads to development of a values-led Critical Functional Appraisal (CFA) framework – a community-centric tool. The CFA proposal is designed to reflect activist needs and support decision-making while ensuring the longevity of narratives over time.

Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (see Fig. 1.1) are complementary frames for addressing societal grand challenges such as social justice imperatives.[3] A community of academics and educators are going beyond the apparent to reveal hidden agendas, concealed inequalities and tacit manipulation [4] to explore multidimensional accounts of archives and recordkeeping and question societal dynamics for a fairer world. Continuum scholars seek to reveal established power and exclusion in an archival multiverse.[5] The archival multiverse is a “plurality of evidentiary texts” developed by a person, community or group for memory-keeping[6] to ensure equitable societal representation, continuum research progresses analysis of practices beyond narrow and exclusionary archival narratives and systems in institutional and collecting archives.[7] Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model provide a foundation for exploring societal functions in a multitude of ways and contexts.

Fig. 1.1 The Records Continuum Model.[8]

image description

Click on the elements in the below descriptions to learn more about each part of the model, noting that they are not discrete sections but blend and blur across boundaries in a continuum of activity.

The emphasis of the research is to understand and document activists’ recordkeeping systems, relationships and actions, not the end-point records of individuals or groups. It considers the holistic view of a social movement over time and space continuum-style.

A records continuum mindset emphasises acknowledging the intricate layers and complexities inherent in societal recordkeeping practices while challenging prevailing power structures.[9] Acknowledging the critical nuances in evidentiary cycles across a social movement gives rise to the concept of radical recordkeeping, a term used to disrupt the status quo of archiving and to advocate for communities engaging in self-determined assessments of their records and risks associated with remembering and forgetting.

What is Continuum-based Participatory Appraisal?

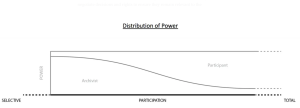

A participatory approach to appraisal puts the power into the hands of community members, whereas traditional notions of archival control has previously focused on the ‘selective’ side of Mackay’s spectrum of participation[10] (shown below).

Fig. 1.2 Visualization of the participatory spectrum.

image description

In a participatory view of archives, the distribution of power is variable depending on the approaches taken to be inclusive and respectful of community autonomy. One hundred percent power to participants means control, ownership and appraisal decision-making by and for the community themselves, perhaps only with fleeting or selective collaboration with archives and archivists.

From a Records Continuum viewpoint, appraisal serves as a fundamental aspect influencing the representation of societal traces and groups within society. Over time, the emphasis in appraisal practices has shifted toward analyzing the functional aspect of records rather than solely assessing the intrinsic value of artifacts within organizations (in an idealism called macroappraisal). This shift has become the norm, focusing on records’ roles and purposes in fulfilling organizational functions rather than just an items inherent ‘value’.

However, there exists a significant gap in appraisal discourses, particularly concerning a lack of community-focused perspectives that transcend institutional or organizational boundaries.[12] To comprehensively grasp the risks associated with remembering and forgetting in the context of animal activism, a shift towards a continuum-based appraisal approach becomes a radical prospect for traditional institutional settings reliant on government-focused collections of artifacts.

Adopting a continuum perspective in the appraisal process necessitates a broader understanding that extends beyond the mere functional assessment of records. It involves considering the multifaceted social, cultural and political contexts in which records are not only created but also actively utilised. This approach acknowledges that records are not static entities, but dynamic elements deeply intertwined with the socio-political fabric of their creation and utilization.

A continuum-based participatory appraisal framework aims to transcend the conventional organizational boundaries, delving into the intricate layers of societal and community contexts. By recognizing the broader socio-cultural implications and significance of records within animal activism contexts, this approach enables a deeper understanding of how these records are shaped, utilised and potentially marginalised or excluded within the larger archival landscape. In essence, a continuum-based appraisal view advocates for a holistic understanding of records, positioning them within their wider societal and cultural contexts. It acknowledges the dynamic interplay between records, societal values and the socio-political milieu, emphasizing the need to appraise records not just for their functional utility but also for their intrinsic role in preserving diverse narratives and representing marginalised societal groups.

Participatory Appraisal: Enacting Recordkeeping Autonomy

Definitions of participatory archives and recordkeeping have sometimes referenced appraisal as part of a democratised and equitable approach; to include communities in the memorialisation of its own archives. However, community autonomy in appraisal has yet to be articulated in detail in continuum terms. The ability of communities to appraise their records within non-participatory institutions is limited, since they are born from a different age, paradigm and politics that reinforce traditional power relations.[13] Participatory appraisal means that archivists can review their role in community archiving and the skills and values they bring to support communities in their self-determination. For example, rather than viewing participation as a post-hoc exercise of applying archival practices after record creation, participation can potentially embed critical continuum values and approaches.

Participatory approaches champion a collaborative approach to co-creatorship and shared roles in recordkeeping. Applying participation is an attempt to bridge the gap of power inequity between institution and citizen by advocating citizen rights and their role as more than mere subjects of the record or as metadata harvesters. Activists can acknowledge participants’ values and rights to autonomy and agency.[14] The participatory movement advocates for the importance of self-determination and autonomy in recordkeeping and archiving, particularly for marginalised groups.[15] The definition of archival autonomy arose from this work and can extend to the autonomy of recordkeeping for activists, including their participatory appraisal.

Participation and democratisation of the archival endeavour has been identified as one of the grand archival challenges facing society today

… to enable citizens to participate in the constitution of the archives and to fully exercise their rights to access archival sources of information.[16]

Archival foundations of provenance, original order and description are increasingly being questioned regarding their inherent power, violence and discrimination in the archives.[17] However, there is generally a focus on description with less attention paid to appraisal in participatory social justice, library and information science literature.

The participatory nature of appraisal, in particular, is also scant in theoretical or practical detail. Meanwhile, predominance of bureaucratic worldviews and methods of recordkeeping risk the collective memory of entire communities,[18] which is particularly true for those calling for radical change. A model that respects activist community worldviews can be created for appraisal, which embraces multiple voices and provenances.

The Crucible of Animal Rights and the Potential of Critical Functional Appraisal

This book takes a critical continuum perspective to analyse the challenges and potentials of recordkeeping within the context of animal rights activism. It seeks to explore how this approach can offer new insights into the appraisal of records across boundaries of power and contribute to the discourse on creating more inclusive and participatory archival practices aligned with the needs of diverse communities and societal movements. Within the expansive landscape of social movements, the realm of animal rights advocacy emerges as a poignant and exemplary case study showcasing the transformative potential of a Critical Functional Appraisal approach. For decades, advocates within the animal rights movement have ardently fought to liberate sentient beings from the shackles of cruelty and objectification, thereby influencing societal perceptions and norms. This movement serves as an ideal crucible to explore the power and efficacy of a CFA due to several pivotal reasons.

Firstly, animal rights activism encapsulates a deeply rooted and longstanding struggle against entrenched societal norms and ingrained practices that objectify and exploit animals. The multifaceted nature of this movement requires a nuanced understanding of how records, narratives and advocacy strategies intersect and evolve over time. A CFA enables the community with a tool to dissect and comprehend the complexities inherent in their struggle, shedding light on the interplay between records, societal attitudes and legislated injustice.

Secondly, the animal rights movement grapples with pervasive challenges in representation within archival institutions. Governmental archives often prioritise records related to the policing of animal activists or support industries that profit from animal exploitation. This lack of representation underscores the necessity for a CFA framework that recognises and addresses the gaps in preserving authentic narratives and voices crucial to understanding the movement’s evolution. Moreover, the narratives within animal rights advocacy are inherently diverse, spanning various causes, stories and successes. These multifaceted narratives, often overlooked or sporadically documented, offer a rich tapestry that a CFA approach can identify and revere. By focusing on the authentic voices of activists, a CFA framework seeks to bridge the gap between traditional archival practices and the essential narratives needed to comprehensively document the movement’s history.

Lastly, the animal rights movement embodies a continuous struggle for recognition, faced with challenges of being labelled as criminal, minimised and ridiculed depending on societal perception. The application of a CFA lens in this context offers a unique opportunity to both call out as well as navigate the complexities of recordkeeping, societal justice and structural challenges faced by a movement seeking radical change to status quo. For example, the dissemination of evidence of animal abuse can lead to legal repercussions, including prosecution and lengthy prison terms for activists engaged in this form of documentation.[19] This precarious situation poses a significant challenge for animal activist groups, compelling them to navigate a fine line between exposing animal cruelty and avoiding legal entanglements. Moreover, limitations within the legal system often obstruct the presentation of essential records to jurors, creating hurdles in substantiating activists’ claims in court.[20] Despite these obstacles, the efforts of activists in sharing evidence and storytelling have significantly raised awareness of animal rights issues and, in some instances, led to victorious legal battles waged against them.

Narratives, Power and Biased Archival Visibility

Society’s dominant narratives weave their threads with remembrance and reinforcement, creating a tapestry of collective memory. However, the threads of dominance often are sewn by systems of government that selectively forget, systematically exclude, or even criminalise those who challenge the status quo. In the archival context, the narratives that secure the most prominence are often the ones with the backing of substantial funding and institutional support.

Organizations equipped with the resources to fund and strategically plan for the protection and collection of their records wield a certain longevity in preserving their history and knowledge. Their narratives are not merely remembered but are actively supported and resourced for the long term, providing a sense of continuity that shapes the broader societal understanding. In this privileged space, the pathways for archiving the records of such organizations are seemingly assured, contributing to the perpetuation of specific historical perspectives.

Yet, the landscape of recordkeeping encounters treacherous terrain when challenging established narratives. The evidencing of counternarratives by activists becomes a precarious endeavour, marked by control, surveillance and restriction imposed by external powers. These powers, capable of wielding labels such as ‘criminals’ or ‘terrorists’, cast a shadow over the very voices seeking to challenge the dominant discourse.[21] The struggle for archiving becomes not only a logistical challenge but a profound societal, social justice and structural dilemma.

In the face of such challenges, the archival landscape risks becoming a monolithic repository, echoing only the narratives that align with the existing power structures. This poses a significant threat to the multiverse of narratives that should rightfully inhabit our archives – a rich reflection of perspectives on the diverse struggles, triumphs and aspirations of social movements. This book investigates the complexities of societal, social justice and structural recordkeeping challenges, exploring the ways in which external forces perpetually marginalise the voices of those challenging the established order. The overarching question emerges: How can we ensure the preservation and accessibility of a diverse array of narratives that represent the true essence of radical social change?

In Summary

By shifting the focus from legislatively oriented appraisal methods to ones grounded in community values, emotions and narratives, this book advocates for a positively disruptive participatory archives movement. As the status quo of institutional dominance is continually questioned, the call for community-focused and community-run appraisal echoes a transformative step toward more equitable archival structures.

A critical continuum approach acknowledges the collaborative creation of records by multiple communities, challenging the notion of a single creatorship or authoritarian ownership of records. This approach is particularly relevant in the contemporary era, where technological advancements facilitate co-creation and collaboration in appraising records across institutional and individual boundaries.

The author here acknowledges bias and unapologetically values the strategic witnessing techniques employed by activists. Global grassroots movements, like the animal activist movement for example, leverages online records to drive immediate, short-term and long-term social change, emphasizing the need for equitable archiving in online platforms.

- Jarvie, Katherine. 2023. Radical Recordkeeping — Re-thinking Archival Appraisal. Monash University. Thesis. https://doi.org/10.26180/23512005.v1 ↵

- Jarvie, Katherine. 2023. Radical Recordkeeping — Re-thinking Archival Appraisal. Monash University. Thesis. https://doi.org/10.26180/23512005.v1 ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September 2012, p.106) ↵

- Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish and Greg Rolan. 2017. “Critical Approaches to Archiving and Recordkeeping in the Continuum.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1 (2): 1–38, p.2. ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79–88. ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse, and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September 2012, 106-7). ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79-88. ↵

- Upward, 2004. (Used with permission) “The Records Continuum and the Concept of an End Product.” Archives & Manuscripts, May. ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery” & Upward, Frank. 2019. “The Monistic Diversity of Continuum Informatics.” Records Management Journal, 29 (1/2): 258–71. ↵

- Mackay, Heather. 2019. “The Participatory Archive: Designing a Spectrum for Participation and a New Definition of the Participatory Archive.” Medium. April 29, 2019. https://medium.com/@mackayhjc/the-participatory-archive-designing-a-spectrum-for-participation-and-a-new-definition-of-the-964bc1b0f987. ↵

- Mackay, Heather. 2019. (Used with permission) “The Participatory Archive: Designing a Spectrum for Participation and a New Definition of the Participatory Archive.” Medium. April 29. https://medium.com/@mackayhjc/the-participatory-archive-designing-a-spectrum-for-participation-and-a-new-definition-of-the-964bc1b0f987 ↵

- Beaven, Brian P.N. 1999. “Macro-Appraisal: From Theory to Practice.” Archivaria, 48, January: 154–98; Cook, Terry. 2011. “‘We Are What We Keep; We Keep What We Are’: Archival Appraisal Past, Present and Future.” Journal of the Society of Archivists, 32 (2): 173–89 & Baxter, Terry. 2019. “The Doorway from Heart to Heart: Diversity’s Stubbornly Persistent Illusion.” Journal of Western Archives, 10 (1). ↵

- Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, Elizabeth Daniels and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Self-Determination and Archival Autonomy: Advocating Activism.” Archival Science. p.355. ↵

- McKemmish, Sue, and Anne Gilliland. 2015. “Rights in Records as a Platform for Participative Archiving.” In Archival Education and Research: Selected Papers from the 2014 AERI Conference, edited by R J Cox, A Langmead, and E Mattern, 101–31. UCLA,115-6. ↵

- Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, Elizabeth Daniels, and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Self-Determination and Archival Autonomy: Advocating Activism.” Archival Science, 15 (4): 337–68. ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September, p.106. ↵

- e.g. Caswell, Michelle, Alda Allina Migoni, Noah Geraci and Marika Cifor. 2016. “To Be Able to Imagine Otherwise: community archives and the importance of representation.” Archives and Records 38, no. 1, December: 5–26.; Drake, Jarrett. “Seismic Shifts: On Archival Fact and Fictions.” Sustainable Futures, Medium blog, 2018. https://medium.com/community-archives/seismic-shifts-on-archival-fact-and-fictions-6db4d5c655ae; Findlay, Cassie. 2016. “Archival Activism.” Archives and Manuscripts, 44, no.3, September: 155–159; Ghaddar, JJ and Michelle Caswell. 2019. “To go beyond: towards a decolonial archival praxis.” Archival Science 19, no. 2 June: 71–85; Winn, Sam. “The Hubris of Neutrality in Archives.” On Archivy – Medium, April 2017. https://medium.com/on-archivy/the-hubris-of-neutrality-in-archives-8df6b523fe9f & Wright, Kirsten. 2017. “The power imbalance inherent in records and archives,” July. https://www.findandconnectwrblog.info/2017/07/the-power-imbalance-inherent-in-records-and-archives/. ↵

- Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September, p.109. ↵

- Chappell, Bill. 2017. “Judge Overturns Utah’s ‘Ag-Gag’ Ban On Undercover Filming At Farms.” NPR: The Two-Way, July 8, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/08/536186914/judge-overturns-utahs-ag-gag-ban-on-undercover-filming-at-farms; Guillermo, Emil and Jeremy Beckham. 2022. “The PETA Podcast: Animal Rights Victory in Utah over Smithfield, Factory Farming on Apple Podcasts.” October 12. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/animal-rights-victory-in-utah-over-smithfield-factory/id1345723714?i=1000582378526). ↵

- Hsuing, Wayne. 2022. “Our Judge in Utah Just Ruled to Exclude Evidence of Animal Cruelty at Trial.” All Creatures.Org, February 24. https://www.all-creatures.org/litigation/litigation-judge-excludes-cruelty.html. ↵

- Potter, Will. 2011. Green Is the New Red: An Insiders Account of a Social Movement under Siege. San Francisco: City Lights Books & Webb, Maureen. Forward by Doctrow C. 2020. Coding Democracy: How Hackers Are Disrupting Power, Surveillance, and Authoritarianism. The MIT Press. ↵

"… disruption of traditional recordkeeping paradigms in revolutionary or profound ways by groups and recordkeeping and archiving professionals who challenge or disrupt social or mainstream norms."

Jarvie, Katherine, Greg Rolan, and Heather Soyka. 2017. “Why ‘Radical Recordkeeping’?” Archives and Manuscripts, 45 (3): 173–75, p.173.

Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) are complementary frames for addressing societal grand challenges such as social justice imperatives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106). This framing is described here as critical continuum research. A community of academics and educators are

… going beyond the apparent to reveal hidden agendas, concealed inequalities and tacit manipulation (Evans et al., 2017, 2) …

to explore multidimensional accounts of archives and recordkeeping and question societal dynamics for a fairer world. Continuum scholars seek to reveal established power and exclusion in an archival multiverse (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). The archival multiverse is a “plurality of evidentiary texts: developed by a person, community or group for memory-keeping” (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106-7). To ensure equitable societal representation, continuum research progresses analysis of practices beyond narrow and exclusionary archival narratives and systems in institutional and collecting archives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1997) provide a foundation for exploring societal functions in a multitude of ways and contexts.

References

Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish and Greg Rolan. 2017. “Critical Approaches to Archiving and Recordkeeping in the Continuum.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1 (2): 1–38.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse, and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September 2012.

Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79–88.

Upward, Frank. 1997. “Structuring the Records Continuum (Series of Two Parts) Part 2: Structuration Theory and Recordkeeping.” Archives and Manuscripts, 25 (1): 10–35.

Records can be described "... as persistent representations of activities, created by participants or observers or their authorized proxies ... [with a] role in providing evidence, information, or memory."

Yeo, Geoffrey. 2007. “Concepts of Record (1): Evidence, Information, and Persistent Representations.” The American Archivist, 70 (2): 315–43. p.343.

This book supports a transition away from the traditional definition of appraisal to a continuum of actions, for example, from:

"... the process of determining whether records and other materials have permanent (archival) value" Pearce-Moses, Richard (2005). A Glossary of Archival & Records Terminology. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists

towards the following

"… multi-faceted, recursive process which begins with defining what should be created Dimension 1, what should be captured and managed as record Dimension 2, what should be managed as a part of individual or organisational memory Dimension 3 and what should be pluralised beyond organisational or individual memory Dimension 4."

McKemmish, Sue. 2017. “Chapter 4: Recordkeeping in the Continuum. An Australian Tradition.” In Research in the Archival Multiverse, edited by Anne Gilliland, Sue McKemmish, and Andrew Lau, 122 – 160. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: Monash University Publishing. p.141.

Understandings of participatory archiving (including participatory appraisal) reflects Huvila, Isto. 2008. "Decentralised Curation, Radical User Orientation, and Broader Contextualisation of Records Management”, Archival Science, 8 (1): 15–36.

In Continuum terms, appraisal is part of recordkeeping, and an example of a participatory model of agency, inclusive socio-technical infrastructure, action and inscriptions as influences on decision making is extended by:

Rolan, Gregory. 2016. “Agency in the Archive: A Model for Participatory Recordkeeping.” Archival Science, 17 (3): 1–31.

Critical functional appraisal (CFA) emphasises the analysis and understanding community functions and activities that produce records. This method, with its critical focus on power dynamics, social justice, and rights in recordkeeping. The CFA considers the broader social and political context in which records are created and used. In the context of animal activist communities, critical functional appraisal can help identify and preserve records that reflect the experiences and challenges of these individuals, groups and movements, ensuring that their voices and efforts are represented and valued in the long term.

"An analysis of the functions of an organization to determine the relative importance of those activities and set priorities for documentation. Macroappraisal identifies the activities and the records and is followed by microappraisal to determine which records are kept permanently."

Society of American Archivists (SAA), SAA Dictionary, (Accessed 29 12 2023) https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/macroappraisal.html

In Records Continuum terms, Appraisal is "a multi-faceted, recursive process which begins with defining what should be created (Dimension 1), what should be captured and managed as record (Dimension 2), what should be managed as a part of individual or organisational memory (Dimension 3) and what should be pluralised beyond organisational or individual memory (Dimension 4).”

McKemmish, Sue, Barbara Reed, and Frank Upward. 2009. “The Records Continuum Model.” In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences, edited by Marcia J. Bates and Mary N. Maack, 3rd ed., 4447–59. Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL : CRC Press.

"... the ability for individuals and communities to participate in societal memory, with their own voice, and to become participatory agents in recordkeeping and archiving for identity, memory and accountability purposes."

Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish, Elizabeth Daniels, and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Self-Determination and Archival Autonomy: Advocating Activism.” Archival Science, 15 (4): 337–68.