7 Visualising Nanosecond Archiving, Identity and Ambience

With a focus on how radical recordkeeping informs the Records Continuum Model (RCM), this chapter builds upon the functional analysis of direct action conducted in the previous chapter, whilst considering emotion (e.g. negotiating conflict and eliciting anger), risk and also strategic witnessing as part of the modelling. The RCM can be used as an analytical tool to navigate and represent the complexity of activist recordkeeping activities, people and risks in their relational entanglement. The concept of strategic witnessing, is used as inspiration for enhancing the RCM with an activist community lens. The RCM is adapted in this chapter to reflect the conflicting debates and voices within and outside the animal liberation community itself and the threat of anticipatory witnessing by authorities. A continuum view of modelling and analysing the activist recordkeeping landscape is explored to deal with complex identities and concepts of societal provenance and irreconcilable ontologies. This is important because activist recordkeeping intertwines with individuals with opposing values and worldviews (for example, with those policing or critiquing direct action). In continuum modeling, there is an opportunity to represent multiple stakeholders who may support or oppose a social movement, with these groups and individuals engaging in various forms of simultaneous recordkeeping. To reflect this radical recordkeeping, new models include the representation of the anticipatory power of witnessing and consider the dominant forces that shape or limit activism.

Nanosecond Archiving in Distributed Platforms

The ability for records to be created across the continuum using online platforms is a feature of radical recordkeeping, memory-making and activism. This nanosecond archiving happens in complex ways, with immediate needs met through the device or platform used and the manual or automated decisions set by the user or administrator. The discussion below outlines the development of ways to represent these activities, decisions and actions on the Records Continuum Model. It builds from the knowledge gained from the group Direct Action Everywhere (DxE) as a case study in their style of direct action activism for animal liberation. DxE makes access and sharing decisions by using specific platforms or adjusting settings in these shared platforms. Modelling this activity was the first step to understanding how the Records Continuum Model can be used to reflect these actions and relationships.

Layers of Community Recordkeeping in the Continuum

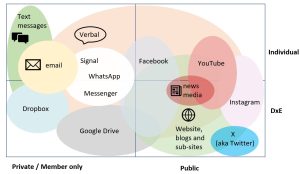

An example analysis of DxE’s social media and online landscape (reproduced here in Figure 7.1) has shown that DxE manages records in public and individual member spaces, with the visual mapping to quadrants of access, reach and audience. It attempts to model the overlapping nature of animal activists’ personal and collective recordkeeping and the blurring of boundaries between personal activity and group records.

Fig. 7.1 Quadrants of Recordkeeping.[1]

This mapping of radical recordkeeping across platforms can be understood through a quadrant system where the y-axis represents ‘individual (in this case a DxE activist)’ and ‘group (in this case DxE)’ and the x-axis represents ‘private’ and ‘public’ spaces; based on the nature of the records and their intended audience. Below is a description of each quadrant with descriptions of examples from Figure 7.1, their purpose and importance.

Private-Individual:

Purpose: To capture personal experiences and reflections that are not intended for public dissemination.

Examples: Personal diaries, private journals and confidential notes.

Importance: Provides a space for individuals to document their personal journeys and inner thoughts without external scrutiny.

Public-Individual:

Purpose: To share personal testimonies and individual experiences with a broader audience.

Examples: Profile pages, personal blogs and podcasts shared on public platforms.

Importance: Highlights individual narratives, bringing personal perspectives to the forefront and humanizing the movement.

Private-Group:

Purpose: To document the internal operations and strategies of the group that are not intended for public view.

Examples: Internal action plans, meeting minutes and confidential communication.

Importance: Ensures the group can operate effectively and transparently internally while protecting sensitive information.

Public-Group:

Purpose: To share the collective memory and reflective records of the group with the public.

Examples: Investigative reports, official statements and direct-action video published on group platforms.

Importance: Promotes transparency and public awareness of the group’s activities, challenges and achievements.

This method of analysis emphasises a balanced approach to recordkeeping, considering both individual and group contributions, as well as private and public contexts. This ensures a comprehensive and inclusive documentation of a group’s activities and experiences online. Additionally, mapping recordkeeping in this way can elicit the diverse types of platforms used and their significance and or fragility as long-term archives. It can be a preparation for an effective appraisal plan or documentation strategy, ensuring that critical records are preserved and accessible for future use.

Platforms can be designed wholly in one quadrant or be used across the quadrants depending on the policies or rules of the group. While examples of types of records created, managed and stored in platforms is described above, it is the activity that is the important aspect of analysis. Representation of this activity across the RCM is shown in Figure 7.2 below, including the different layers of individual and community action. Some arrows and ovals in Figure 7.2 traverse into broader audiences and users, whereas DxE-only records stay in secure platforms to be kept for DxE, chapter or individual access.

Note: this representation is of four examples of nanosecond archiving from each quadrant and is not a static decision – this can change over time as new decisions are made. (Click on the ‘?’ in the image for more detail).

Fig. 7.2. Translating the Quadrants of Recordkeeping (Fig. 7.1) into the Records Continuum Model.

While different shapes separate the mapping of the different layers of individual, group and public records in Figure 7.2, the nanosecond archiving across each of the four dimensions is difficult to visualise. One oval or arrow means overlapping activity is happening all at once. For example, records created by DxE can also be made available for public view by default. If there was a more incremental path to archiving steps, other shapes could be added to the model to map the journey across the continuum. In mapping this complexity, ‘Platforms’ and ‘Internet’ have been added to the RCM axis (in red text) to describe how radical recordkeeping is represented on the model for this activist community context.

New Labels on the Recordkeeping Containers Axis

The Platforms and Internet labels in Figure 7.2 represent the ‘archives’ of DxE’s radical recordkeeping and animal liberation. The evidence gathered and shared by DxE across their online spaces can be considered digital bundles of identity, memory, records and community – shared in a distributed network on the Internet. Continuum theory and the RCM can help archivists rethink modern day containers, archives and platforms as an archive. The RCM captures the verbal and written or performed activity in the ‘recordkeeping containers’ axis. These are both formal and informal records online and offline that build the community network and share ideas and strategies. These digital bundles operate in a continuum of action and can be considered fractals and ‘archives’ are part of a view of information ecology.[2] There is a “fractalisation … in digital information ecologies” with dispersed records across online applications and sometimes with dispersed parts (e.g. metadata, trace, copies, versions or layers stored separately rather than in one location). The organic nature of these patterns, the seen (above ground) and the unseen (underground), the blooming and ongoing recurrence of a network of fungus is another form of fractalisation that is just as difficult to map and visualise. However, observing patterns in an organisation [and community group] teaches us how to analyse patterns in “bundles of activities” online.

… applications [or platforms] will be the digital era’s equivalent of the series in the paper era – fractals that combine data and information tasks and can be used to address the backward and forward compatibility of both on an application-by-application basis. Informatics professionals can build tailorable and modular architectures around the old concept of organisations as bundles of activities.[3]

Radical recordkeeping is a continuum of action that Frank Upward and colleagues have referred to as perduring over time in dispersed networks. Different views of versioning and digital archives in the archival multiverse are always becoming but cannot be bounded by the organisation alone. By acknowledging the different individuals, actors, groups and social movements that an activist group shares (values, goals, relationships and actions), the broader recordkeeping landscape can be accounted for as a multiverse of records, narrative, evidence and memory. Considering the multiple realities of supporters, opponents, law enforcement and others, the notions and understandings of irreconcilable ontologies and autonomy (or identifying the lack of it) archived on platforms and online can be identified using the RCM.

Digital Identities Across Platforms

Thinking of platforms as digital bundles of patterned information there is an opportunity to understand identity as integrated in these records, distributed across online platforms. All groups, movements and individuals can have disparate data and records scattered online, purposefully, unintentionally or strategically. The addition of the complementary labels to the recordkeeping containers axis on the RCM (in red text in Figure 7.2 above) allows for a more nuanced analysis of identity in platforms and how they are enacted in activism online. Purely personal online archives can no longer be individuated because of the inherently networked relationships across distributed platforms.[4] The RCM allows for analysis of how this operates in practice. Social media profiles, for example, can be personalised to an individual level, potentially locking a record down to diary-like use. But as a ‘personal archive’, there are multiple interactions and relationships in using these platforms online. A record can be shared, commented on and added to. As an archive for a networked identity, radical recordkeeping incorporates collective identities across platforms in ways that support ideas of disparate identities across a multiverse, where there is an:

… infinitely reproducible and algorithmically generated data profile of contacts and keywords that defines a user as “dividual” [using Deleuze’s terminology that emphasises multiplicity and divisions] or “instance” within a larger, relational database.[5]

So individuals are interconnected by multiple relationships in an online platform and network. Their profile identity is not simple – it is decentralised across multiple places online in pluralised ways. Activists can express multiple identities across several platforms strategically – someone may choose to express their action in specific media and profiles and not others, or it may proliferate into other platforms. Such actions can create fractal identities online.[6] Relationships in these platforms can be partitioned and evolve across each separate network. Social media posts are integrated with identity and curated (appraised) via decision-making on what trace belongs on which platform (or at all). Groups or individuals add metadata to posts and interlayer traces with their context and shared or different record-making values. These decisions are appraisal decisions on accessibility and sharing. Audiences can provide additional context for decision-making of long-term or short-term value.

Figures 7.1 and 7.2 above show the blur between individual activists and the collective across distributed platforms and in-person interactions. The RCM’s benefit in representing this blur is that complex representation of provenance is shown as the interaction (e.g. between the recordkeeping containers and identity axes). The aim of the model is to transcend prescribed boundaries or rigid categorisation. For example, activists might be part of multiple organisations and recordkeeping for DxE or other activism groups simultaneously in their online spaces. The emphasis on non-linearity and movement between boundaries is the part of the critical need for representing identity in activism in a nanosecond. The RCM is not static and despite its placement across each dimension, the identity axis does not have defined boundaries for individual recordkeeping. For example, we could adapt the identity axis to a non-linear representation – to suit dynamic activist identities in the radical recordkeeping continuum. An example is in Figure 7.3 below – the blue arrows swirl throughout the cone to represent non-linear interactivity between each of the identities.

Fig. 7.3 Dynamic Representation of Activist Identity in Society Across the Continuum.

Pluralisation of records can happen at any point by any of these identities in Figure 7.3. ‘Social Movement Ambience’ in this case, is the animal activist movement as an example, linking back to the idea of a shared ambient function across groups in recordkeeping. Still, other activist groups can learn and grow from this recordkeeping, for example, using the same techniques for direction in their own context.

Using this same idea, an activist group within a social movement can share a function (e.g. direct action) and group identity. Figure 7.3 attempts to describe activists’ non-linear representation, collaboration and connection through recordkeeping. This dynamic shape of the cone has influenced representing radical recordkeeping across the RCM. Additionally though, to be truly ambient, the focus of this cone not only needs to be on activists but also consider opponents, audience and power structures that impact activist recordkeeping. This means re-thinking a simple cone shape of one axis to one that accounts for the multiple simultaneous provenance occurring in the archival multiverse.

Ambient Functions and Purpose

In starting to visualise distributed identities as part of activism and its relationships, an attempt to map these identities to the (Trans)actionality axis of the RCM is shown in Figure 7.4 below. In activism, there is not one simple organisational membership that is traditionally seen in archival provenance. Non-members can create records adopted for use by others. Members of multiple groups too can collectively contribute to the group and the movements’ societal memory to build community knowledge. All axis labels in the continuum (transactionality, recordkeeping containers, evidentiality & identity) are ambient because they can have a broader impact beyond the ambient group or individual performing recordkeeping and have linkages and shared contexts. However, the driver for these recordkeeping transactions varies in purpose and function. Individuals and groups share some drivers within the activist movement and some are unique – acknowledging that individuals and groups in a social movement do not need to combine to act as a cohesive whole.

Fig. 7.4 Ambient Societal Provenance & Functions of a Social Movement, Communities and Individuals – Drag and Drop Activity.

Figure 7.4 shows examples of shared and ambient purpose for DxE’s broader movement is achieving social change for the benefit and wellbeing of animals. Linear expressions from left to right have been avoided to show the variance in ‘shared’ and ‘unique’ functions and purposes across a variable community of identity. Animal rights groups for example, can include ones that fall short of valuing species equality but believe in the other values expressed as DxE’s purpose. People identifying as DxE members or supporters may believe in some or all of the functions and purposes of DxE shown above and may add their own specific purposes motivated by beliefs, goals and context.

Figure 7.4 looks to represent the overarching functions and purposes of ambient groups. For DxE, primary functions relate to direct action for the right to rescue. Multiple simultaneous provenance accounts for the records generated by multiple individuals with a stake in a record. Individuals participate in sharing the animal and activist experience outside their affiliation with DxE, posting to social media or similar to demonstrate their feelings or activist identity within a broader social movement. Members of DxE can participate in group organising and activities – and these activities may or may not align with the values or goals of the broader social movement. For example, open rescue and the right to rescue is a unique and controversial technique by DxE and may not be embraced by a non-homogenous activist movement. The ambient functions incrementally take the case forward through the evidential, transactional and socio-political change activists hope to enact over time. Animal activists may be geographically and philosophically separated. However, through community building and sharing their own legislative and political contexts, they can come together through recordkeeping with shared purpose and functions for the benefit of animals.

Societal Provenance and Ambience of Recordkeeping

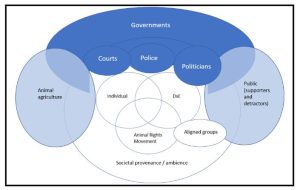

The dynamism of identity in Fig. 7.3 and Fig. 7.4 still paints a simplified view of provenance and relationships of radical recordkeeping by DxE, a straightforward set of identity groups, with the social movement the overarching identity of DxE and its members. The animal rights movement itself is not homogenous. Individuals can move in and out of a group or movement over time, identify or not identify as a member but still support DxE. The movement has varied values, philosophies and approaches. Another version of individual and collective relationships is mapped below.

Fig. 7.5 Representation of Ambient and Societal Provenance Relationships of Records.

In Figure 7.5 above, there are records by DxE, about DxE and against DxE which can come together in distributed ways to create a holistic archival picture of animal activism. DxE’s records can end up in government archives (e.g. police files) in animal agriculture files (as evidence against them). Considering opponents with irreconcilable values and records descriptors (e.g. rescue versus theft) means that relationships, functions and archival description have a long way to go to achieve a unified implementation of a complex metadata model. In the meantime, understanding where these interrelationships and irreconcilable ontologies are mapped onto the RCM can be the first step to understanding interoperability and continuum-based archival standards to support the activist community. Figure 7.5 reflects complex relationships across the continuum in society. As metadata modellers have discovered, representing societal provenance becomes a difficult exercise when data types and standards have to come together to interoperate.

The dark blue circles in Figure 7.5 reflect the dominant narratives and power of society that impose structures that favor long-term records kept about activists. These records can threaten or tell one-sided narratives about the activist groups (represented by white circles). In understanding a multiverse of action, multiple ontologies, worldviews and identities need to be recognised. To accommodate these different ways of knowing and activist patterning, modelling must reflect the dominant and subversive narratives, groups and power relations at play to maintain records over time in the activist’s voice. The records continuum allows for analysing this distributed ambience across a social movement like animal rights. Like the emancipated spectators discussed in chapter five, the power of activist ontology and narratives to overtake dominant knowledge can disrupt capitalist ways of knowing through recordkeeping actions over time and space. This view acknowledges societal provenance through its ambience to visualise powers interacting and competing to induce sense-making and ways of being in society.

Conclusion

This chapter demonstrates the insights that can be gained by visualising nanosecond archiving in activism, along with the dynamic representation of activist identities and ambient multiple simultaneous provenance. There is an analysis here of decisions made across the a continuum of action and is a precursor activity to understanding records for community appraisal in the following chapters. Above, there is an understanding of the fluid and multifaceted nature of activist identities, which helps to understand and document diverse narratives and contributions within social movements and broader activism. Ultimately, this dynamic approach to recordkeeping fosters a holistic understanding of the socio-political landscape of radical recordkeeping.

- Originally published in Jarvie, Katherine, Joanne Evans and Sue McKemmish. 2021. “Radical Appraisal in Support of Archival Autonomy for Animal Rights Activism.” Archival Science, 21, April: 353–372. ↵

- Upward, Frank, Barbara Reed, Gillean Oliver and Joanne Evans. 2017. “Chapter 7. Continuum Thinking as a Building Block for Recordkeeping Informatics.” In Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Victoria: Monash University ePress. ↵

- Upward, Frank, Barbara Reed, Gillean Oliver, and Joanne Evans. 2017. “Chapter 7. Continuum Thinking as a Building Block for Recordkeeping Informatics.” In Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Victoria: Monash University ePress. p.31. ↵

- Acker, Amelia and Jed R Brubaker. 2014. “Death, Memorialization, and Social Media: A Platform Perspective for Personal Archives.” Archivaria, 77 (Spring): 1–23. ↵

- Nunes, Mark. 2013. “Ecstatic Updates: Facebook, Identity, and the Fractal Subject.” In New Visualities, New Technologies The New Ecstasy of Communication, edited by Hille Koskela. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p.12. ↵

- Nunes, Mark. 2013. “Ecstatic Updates: Facebook, Identity, and the Fractal Subject.” In New Visualities, New Technologies The New Ecstasy of Communication, edited by Hille Koskela. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. ↵

Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) are complementary frames for addressing societal grand challenges such as social justice imperatives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106). This framing is described here as critical continuum research. A community of academics and educators are

… going beyond the apparent to reveal hidden agendas, concealed inequalities and tacit manipulation (Evans et al., 2017, 2) …

to explore multidimensional accounts of archives and recordkeeping and question societal dynamics for a fairer world. Continuum scholars seek to reveal established power and exclusion in an archival multiverse (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). The archival multiverse is a “plurality of evidentiary texts: developed by a person, community or group for memory-keeping” (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106-7). To ensure equitable societal representation, continuum research progresses analysis of practices beyond narrow and exclusionary archival narratives and systems in institutional and collecting archives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1997) provide a foundation for exploring societal functions in a multitude of ways and contexts.

References

Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish and Greg Rolan. 2017. “Critical Approaches to Archiving and Recordkeeping in the Continuum.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1 (2): 1–38.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse, and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September 2012.

Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79–88.

Upward, Frank. 1997. “Structuring the Records Continuum (Series of Two Parts) Part 2: Structuration Theory and Recordkeeping.” Archives and Manuscripts, 25 (1): 10–35.

..." a framework through which we can think about the politics of media witnessing as dependent upon audience differentiation, which activists utilize as a tactical apparatus geared toward social change."

Ristovska, Sandra. 2016. “Strategic Witnessing in an Age of Video Activism.” Media, Culture and Society, 38 (7): 1034–37.

Societal provenance refers to the concept that records and archival materials are shaped not only by the organisations and individuals that create them but also by the broader social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they exist. It acknowledges that the creation, management, and interpretation of records are influenced by societal forces, including social norms, power dynamics, community values, and collective memory. Societal provenance expands the understanding of provenance beyond the immediate creator to include the wider social factors that impact the records' creation, preservation, and meaning.

See for example: Piggott, Michael. 2012. Archives and Societal Provenance : Australian Essays. Cambridge UK: Chandos Woodhouse Publishing.

When multiple ontologies are irreconcilable, it means that the differences in these frameworks are so significant that they cannot be harmonised or unified. This can create challenges in managing, accessing, and interpreting archival materials, as different stakeholders may have conflicting views on how the information should be organised and understood.

See Hurley, Chris. 2005. “Parallel Provenance (If These Are Your Records, Where Are Your Stories?).” Archives and Manuscripts, 33 (1 & 2).

The term ‘platform’ is used in this book the way Terri Lee Harel, Muira McCammon and Jessa Lingel refer to them as a discrete but interconnected online space. A digital platform is an online framework or infrastructure that enables the creation, exchange, and consumption of digital content, services, or products. It provides the technological foundation for interactions among users, businesses, and applications, facilitating activities such as communication, commerce, information sharing, and collaboration. Digital platforms often leverage cloud computing, data analytics, and network connectivity to support and enhance these interactions, and can include social media sites, e-commerce marketplaces, content streaming services, and software development environments.

Platforms are also considered here “emergent archival spaces” as defined by Leisa Gibbons.

References

Harel, Terri Lee. 2022. "Archives in the Making: Documenting the January 6 capitol riot on Reddit". Internet Histories, 6(4), 1–21.

McCammon, Muira & Jessa Lingel. 2022. "Situating Dead-and-dying Platforms: Technological failure, infrastructural precarity, and digital decline". Internet Histories, 6(1–2), 1–13.

Gibbons, Leisa. 2020. "Community Archives in Australia: A preliminary investigation. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(4), 1–22.

Instantaneous archiving, usually online and using technology to create, capture, organise and pluralise records (continuum-style), often concurrently. "Nanosecond archiving is a modern reality. It is not its existence that is in question in this book, only its quality."

Upward, Frank, Barbara Reed, Gillean Oliver, and Joanne Evans. 2017. “Chapter 2. A History of the Recordkeeping Single Mind, 1915–2015.” In Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Victoria: Monash University ePress.

In the context of networked communities, a digital bundle refers to a cohesive and interconnected collection of records and information shared and distributed across various online platforms and social media channels.

Jennifer Wemwigans uses the term in the context of Indigenous community knowledge and teachings.

Wemwigans, J. 2021. Keynote: Dr. Jennifer Wemigwans – AERI. Presented at the Archival Education and Research Initiative online conference. Online, July 13.

"Fractals are a mathematical concept: ‘infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales’ (fractalfoundation.org). They are found in nature, and are ‘purely a wonder, iterative and recursive and seemingly infinite. They turn up in food and germs, plants and animals, mountains and water and sky’ (webecoist) ... Fractal patterns also turn up elsewhere in our everyday lives ... they can be seen in art, games, trade, and architecture, around the world."

Hale, Fiona. 2021. “Fractals, Mushrooms, Rhizomes and Scaling Up.” In Making Waves. March 25, 2021. https://makingwaves.network/2021/03/25/fractals-mushrooms-and-scaling-up/.

On fractal online identities, Nunes notes:

We “present” ourselves not as classical subjects, asserting agency; rather, we are subjects only to the extent that we participate in the production of a social world of information as fractal instances of data.

Nunes, Mark. 2013. “Ecstatic Updates: Facebook, Identity, and the Fractal Subject.” In New Visualities, New Technologies The New Ecstasy of Communication, edited by Hille Koskela. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p.13.

This term invites the reader to think about evolving and non-static archiving techniques that moves away from capture of a static artefact, to one that is long-lasting as required with varying and changing methods (in this case decided by the community itself in reaction to evolving needs).

Frank Upward and continuum archivists have used the term perduring in a records continuum context, inspired by Pedurantism in philosophy. Perdurantism - Wikipedia

See for example:

Upward, Frank, Sue McKemmish, and Barbara Reed. 2011. “Archivists and Changing Social and Information Spaces: A Continuum Approach to Recordkeeping and Archiving in Online Cultures.” Archivaria, 197–237.

Upward, Frank, Gillian Oliver, Barbara Reed, and Joanne Evans. 2017. Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Clayton Vic Australia: Monash University Publishing.

The Pluralising the Archival Curriculum Group, which was made up of a large number of international scholars engaged in AERI [Archival Education Reseach Institutes]. They define the archival multiverse as "... encompassing

the pluralism of evidentiary texts, memory-keeping practices and institutions, bureaucratic and personal motivations, community perspectives and needs, and cultural and legal constructs with which archival professionals and academics must be prepared, through graduate education, to engage."

McKemmish, Sue, and Michael Piggott. 2013. “Toward the Archival Multiverse: Challenging the Binary Opposition of the Personal and Corporate Archive in Modern Archival Theory and Practice.” Archivaria. 76, p. 113.

"The record is always in a process of becoming."

McKemmish, Sue. 1994. “Are Records Ever Actual?” In The Records Continuum: Ian Maclean and Australian Archives First Fifty Years, edited by Sue McKemmish and Michael Piggott, 187–203. Ancora in association with Australian Archives.

"Ambience is the context of provenance ... Functions offer one possible tool for crafting ambient relationships. Ambient functions define and give meaning to agents of record-keeping within the context in which they operate."

Hurley, Chris. 1995. “Ambient Functions - Abandoned Children to Zoos.” Archivaria 40 (June): 21–39.

One example of this ambience is having a shared context of animal liberation activism. Chris Hurley’s multiple simultaneous provenances are occurring at a group level for activist group Direct Action Everywhere (DxE), but individuals and the broader movement are also co-creators and stakeholders in DxE records (at an ambient level). Hurley’s description of ambience can also be applied in the animal activism context for ambient identity and ambient purposes.

The Trans in transactionality is bracketed here in this book to show the importance of the action, particularly for activism; and is more important than merely transactions alone (but transactions cannot be discounted, this is more like a sub-group of action).