Positioning yourself as a researcher

Note the way these researchers position themselves in relation to the work of others in their field

Critical literacy is not synonymous with critical thinking, although critical thinking is clearly part of critical literacy [a]. Critical thinking can be described as independent thinking that uses information as the starting point (Klooster, 2001) [b]. It often begins with questions, builds on reasoned arguments and can involve social thinking. While this view of critical thinking is participatory and metacognitive, it remains personal inquiry and does not necessarily require the reader to question the purposes of the text [c]. To be critically literate, one must move beyond individual response and personal discovery to interrogate the curriculum and the everyday world (Cardiero-Kaplan, 2002) [d]. Harste (2001) asserts that readers must question, redesign, and create alternate worlds [e]. They should disrupt the commonplace, interrogate multiple viewpoints, focus on sociopolitical issues, and take action to promote social justice (Lewison, Seely Flint, Van Sluys, 2002) [f].

“Student Views of Learning: Perspectives from Three Countries” by Beach, S. A., Ward, A., & Mirseitova, S., Language and Literacy, 9(1), 2007, https://doi.org/10.20360/G2ZW2W is licensed under CC BY 3.0

In the passage above about ‘critical literacy’ the writers signal their approach to the topic by contrasting two very similar concepts. Statement [a] tells us what the concept isn’t (note the use of the phrase ‘not synonymous with’) and go on to provide a nuanced definition with the use of ‘although’. Statement [c] signals the limitations of our understanding of ‘critical thinking’ (note the use of ‘it remains’ and ‘does not necessarily’) and prepares the reader for the writers’ position presented in the statements [d], [e], and [f]. (Also note, the use of other writers to give weight to these writers’ position).

Identifying the ‘gap’

Research involves highlighting the questions that remain unanswered in your area of research. This is often referred to as ‘identifying the gap’ in the literature and tells the reader what areas need further investigation in your research area. Identifying ‘the gap’ in your research is fundamental to finding your position in an ongoing conversation by deciding how much you accept, question, or reject the claims that your sources make.

When you start to write about that research, you need to figure out how to signal that position, as you quote, summarize, or paraphrase from your sources.

Read the text below and note the way the gap helps the researcher position themselves in the research field.

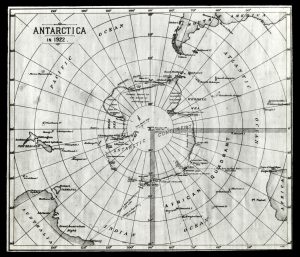

This research project sets out to discover if an experience of Antarctica, specifically mine, could be interpreted through the creation of souvenirs and jewellery. Although Antarctica is considered to be a very remote place it has a long and significant history of science and exploration and most recently has become the destination for tourism [a]. However, unlike most tourist destinations Antarctica has not been memorialised through jewellery and souvenirs in the way of historic tourist locations in the world [b]. Throughout Antarctica’s history explorers have painted images and more recently documented it through photography [c]. Whalers and fishermen have made their own representations of this isolated and uninhabited continent, however, none of these matches the proliferation of souvenirs that have been produced to provide memories and reminders of Europe for example during the times of the Grand Tour or the commonly available souvenirs of popular resorts, sites and locations today [d].

Excerpt from Kirsten Haydon’s dissertation Antarctic landscapes in the souvenir and jewellery (used with permission)