8 Modelling Radical Recordkeeping

The Records Continuum Model (RCM) can be used as tool for analysing complex recordkeeping and relationships in the multiverse. The challenge undertaken was to visualise the radical recordkeeping landscape for an animal rights group. New labels and modelling of the RCM has been tailored to this group and has the potential application for future development for activism in other community groups. The significance of adapting the RCM to this context, is to emphasise the ambient functions and multiple simultaneous provenance of records across society from both supporters and detractors networked across a social movement political landscape.

Figure 8.1 below begins to review the RCM labels – not to replace them but to enhance them for this case study of an animal liberation group. In the title ‘Radical Recordkeeping Continuum Model’, there is an emphasis on the performance and action rather than the objects and artefacts. This was always inherent in the continuum and so is not new; but is a better description for radical recording. Previous modelling of relationships reference both a ‘shared’ and ‘unique’ values and purpose accounts for the non-homogenous vision of each individual, group and movement in relation to each other in and over time. While one group’s campaigning for a ‘Right to Rescue’ animals may be a unique purpose for their actions as an entire group (for example, in the case of Direct Action Everywhere, DxE), individuals supporting this group in the broader movement may have different purposes and motivations for activism. Research was undertaken on how to best map this nonlinear fluidity in a visually flat model.[1] The formation of this shape and new labels to reflect the activity of activism by activists, whistle-blowers and actors within the movement is shown in Figure 8.1 below. These are built from the case study analysis of DxE and from analysis of their identity, evidence, action and recordkeeping containers.

Fig. 8.1 Cone-Shaped RCM with Adjusted Axes Labels for the Radical Recordkeeping Context

In Figure 8.1, the modifications (in red text) have been made to the RCM to address radical recordkeeping insights. The evidentiality axis requires additional explanation described later in this chapter.

Radical recordkeeping and its nanosecond archiving means traces can be created, captured, organised and pluralised all at once. They can be archived on a platform and shared with the broader social movement on the Internet. The Records Continuum Model is used as a visualisation tool to describe and map the ambience and fluidity of radical recordkeeping that incorporates influence and relationships beyond group boundaries. Records Continuum Theory can explain the complexity of activist hermeneutic decisions, identities, their recordkeeping containers and more. Each element of the RCM’s identity axis does not have to stand alone: a person, group or social movement can be represented in multiple ways depending on the recordkeeping under investigation. Modelling one group’s activities against the model is not restricted to an insular view, but also considers their stakeholders and publics’ relationships and shared ambient purposes.

For example, live streams broadcast by DxE aids community building with members, memorialising the struggle for the right to rescue. Live streaming of court proceedings, recorded with the community voice overlaid across the traditional courtroom’s rigid process,[2] balances the power of governmental voice and legislation-led rather than values-led commentary. The immediacy of the recording for communication with its members is the primary purpose of the live stream, but evidentiality can be low due to poor sound quality or due to suppression[3] by the court system. The video is unlikely to survive through time unless saved elsewhere in other recordkeeping containers. Platforms serve as a bundle of the ‘archived’ record. Though not an archive in a traditional sense, the Facebook platform is the location for organising and gaining access to this court video record into the future (albeit limited in search functionality unless described and organised correctly). In the fourth dimension of the model there is influence and learning between other aligned movements and publics past and future –regardless of time or place. The same record can become part of community archives for learning and memorialisation. However, due to the poor quality of the recording, this video may be deleted by the group members – removed from Facebook at any time with the right permissions. A copy of the video could remain stored offline as an archived version. Deletion by Facebook administrators would be a deletion decision by system default or targeted removal. Accepting the risk of this deletion or rot is what has been termed ‘benign neglect’[4] in personal recordkeeping contexts. In contrast, this could be seen as activists applying their radical recordkeeping agency – since, leaving the record in Facebook without a backup copy is a decision about continuing value (or not).

The RCM axes have red markup in Figure 8.1, but the original descriptions have not been erased. In government run settings, a record could include a trace between activist group members as an actor in the court system. Recording transactional evidence in court is entrenched into formalised recordkeeping systems of governance. The police as an organisation are another creator of records about DxE and like Costco, have an irreconcilable worldview of DxE action as an illegal nuisance compared to DxE’s view of right to rescue. Court records are permanently held within an institutional archive but sometimes published online – pluralised and used beyond their original context (for example, websites publishing court-produced transcripts as public records in the USA). DxE has no agency in creating or updating these court records. Even in considering evidence to court, the ‘smoking gun’ of open rescue footage can be inadmissible due to the embedded power and regulations written within the law.

The Radical Recordkeeping Continuum Model

In DxE’s direct action, the power of evidence through recordkeeping is pronounced in its memorialisation of success and strategic witnessing of events to change societal opinion of factory farming and other mainstream norms. In the following section, an analysis of evidence and counternarratives created by individual members for pluralisation to the broader community is considered. A revised evidence axis is proposed for further analysis of power, social change and influence through witnessing. In addition to the evidence axis representing lessons, memories and knowledge of DxE, there is another layer of evidence in radical recordkeeping –termed here as an ‘evidentiality/witnessing’ axis. DxE’s performance of witnessing can include records that are created, deleted, accessed, stored and shared. Additional labels to the RCM’s evidence axis allow for an additional layer of analysis when considering the complexities and intricacies of radical recordkeeping.

Barbara Reed likens the RCM to a ‘chatterbox’ game played by children, where dynamic points of a folded origami pyramid intersect as you move it section by section.[5] Upward refers to this dynamism of analysis as the “dance” of continuum modelling to draw out narratives and analysis through intersections across the model.[6] So too, can RCM axes fold onto each other and provide a new entry into an analysis of recordkeeping processes. For example, the axes on the RCM have an action-structure dynamic where one half of the axis is action-oriented (e.g. evidence – rephrased here for emphasis as ‘evidencing’) and the ‘Recordkeeping Containers’ axis is the structural reflection of its opposite side. A more active term ‘memory making’ is also proposed, to best reflect a continuum of action. To take these continuum mechanics and apply them into the cone shaped model, where each axis can still fold into each other is expressed in Figure 8.2; with additional elements (in red and blue text).

Fig. 8.2 Radical Recordkeeping Continuum Model (RRCM) – Drag and Drop Activity.

The Radical Recordkeeping RCM has newly added complementary witnessing labels and ‘shadow axis’ (in blue text). The new axes labels are placed in the position of axes that best reflect the original ones. So rather than replace them, they act as a complementary overlay to the existing RCM rather than override the original labels. Viral videos, court records and social media objects are counternarratives to the dominant agricultural, economic and political narratives in society – that farmed animals and lab animals (for example) are well treated according to appropriate standards. The identities and societal provenances discussed previously, merge together in the continuum to reflect the dynamism and activism of DxE within a social movement. The counternarratives identified by DxE are traces of activity that defy cultural norms and stories. Some of these traces are in the physical archives, some recorded online, some deleted and some not created at all. This creation or non-creation of records are forms of appraisal.

Rather than just a function of DxE, witnessing and truth-telling of counternarratives through recordkeeping is a powerful technique to create change. Trace remains a core foundation to strategic witnessing pluralised into society to share activist and animal rights counternarratives. ‘Counternarratives’ is used here in the identification of traces to tell activist stories that can be organised into broader memory. The reference to counternarratives has a relationship here to immediate narrative traits used for storytelling and long-term cultural heritage expressed in Upward’s Cultural Heritage Continuum Model.[7] Frank Upward has a ‘storytelling’ and ‘narrative scale’ axis, which is similar here in terms of adapting traces for signification and legitimation through to domination of a narrative. Also, the narrative scale is assessed through sense-making for its potential to grow beyond activist group boundaries into society.

A Shadow Axis of Witnessing and Collective Memory

The addition of a ‘shadow axis’ highlights the power imbalances and irreconcilable worldviews between relationships in the multiverse of an activist group like DxE. The Radical Records Continuum Model (shown in Figure 8.2), like the original RCM, allows for discussion of ambient recordkeeping beyond the activist group itself – with powerful stakeholders performing, preventing and silencing recordkeeping functions across the continuum. The nature of anticipatory witnessing (to prevent acts being seen) was introduced in chapter five. In online platforms, human rights activists have reflected on the shadow banning of their content[8] where platform moderators demote contentious hashtags or activist voices.[9] This demoting activity is done without transparency or admission by the platforms themselves about performing this practice. The suspension of activist profiles on Twitter associated with uprisings in Egypt in 2019 is an example.[10] In response, strategic witnessing tools can include data analysis to compare platform moderation activity across geographies, like a TikTok comparison tool demonstrated at a recent RightsCon conference – that

… enables researchers and journalists to investigate which content is promoted or demoted on the platform, including content regarding politically sensitive issues.[11]

The earlier chapter on strategic witnessing describes the planning of investigations and direct actions that disrupt convention and popular opinion. Yet, it does not completely override the existing label on the RCM called ‘collective memory’. The totality of memory sharing, storing and knowledge dissemination between the animal rights community is broader than strategic witnessing alone. Beyond the collective memory of the movement, the term includes the collective memory of society. Read alongside the identity axis; one can analyse the different groups and individuals making memories together in different ways across multiple geographies and worldviews.

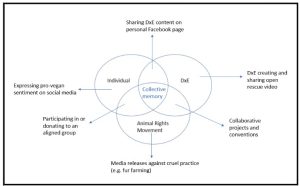

In the context of DxE and its supporters, the kinds of collective memory created and shared at an ambient level (both by individuals and the movement) are shown below as potential DxE records.

Fig. 8.3. Interrelationships for Ambient Collective Memory: Individuals, Group and the Movement.

In continuum style, Figure 8.3 focuses on recordkeeping actions rather than just recording artifacts. With the direct-action focus of DxE, the performance of activism is the focus of action. However, the embeddedness of evidencing and memorialisation is in the performance of recordkeeping. Thinking about the archival possibilities and the outcomes of this research are a new opportunity to further animal rights by understanding distributed recordkeeping and archiving.

Figure 8.3 can represent either a Kantian autonomous agent or radical agent or a combination of both. Their radical recordkeeping together is based on shared principles and purpose. The level of interaction within an activist group and the social movement embodies animal activist identity with their individual and collective performance. What is noticeable in the above figure is the emphasis on action rather than records to create and share collective memory. The shadow axis read against these actions highlights a risk hermeneutic at each decision-making point. These steps as appraisal based on power and shadow relationships are explored further in the next chapter.

Read together, the dominant narratives of the shadow axis are challenged by the new labels on the witnessing axis, alongside the collective memories of an ambient social movement. Using this model, activists have the opportunity to recognise ways their social movement alongside recordkeeping (with evidentiality and memorialisation) can achieve and promote their cause in perpetuity.

Memory Making and Surveillance

The term ‘memory making’ is borrowed from cultural heritage continuum modelling, conflating Gibbons’ ‘memory making’ axis into the organise dimension and is “intrinsically linked”[12] to the evidentiality axis. Gibbons was influenced by Sue McKemmish and Eric Ketelaar’s writing, applying this term to a continuum-based model.[13] Its application here deviates from Gibbons’ Mediated RCM model since not all of animal activism transactions or interactions are mediated ones (compared to Gibbons’ YouTube-based community case study). Instead, memory making is performed across activist groups in their collective design of experiences and memory to influence power-holders to make change and uphold animal justice in society. For Gibbons, memory-making, norms and values are linked. In her model

… memory-making came to be defined as the interaction, interpretation and communication embedded in practices, norms and values which ultimately contribute to the continuous dynamism, iteration and progression of cultural heritage.[14]

And the same can be said for activists where memories continue the progression of activist action as shown in the steps of Moyer’s Movement Action Plan. Values are applied here in memory-making but are also apparent in other parts of the continuum model. Values as a driver for decision-making and appraisal is discussed in the next chapter.

Activists make decisions about their recordkeeping –knowing that powerful actors are surveilling their activity, both overtly and covertly. Surveillance and the potential for reprisals, has led DxE members to use better encrypted and activist-designed messaging apps like Signal rather than WhatsApp. But for functionality’s sake, for example, in their use of the activist organising using the application Discord, the possibility of surveillance on these third-party platforms remains a threat that activists must consider in planning direct action.

Evidencing, Policing and Analysing Power

The risk hermeneutic is exemplified by the assessment of platform use and outreach. Assessment can consider mediation risks, custodianship and ownership issues. This continuum of relationships between moderators and risks of shadow banning is implicit along the new witnessing axis in Figure 8.2. For example, in their use of some social media platforms, there is limited autonomy for controlling the visibility of these posts that applies opaque algorithmic rules (and can also take down records without warning). In imagining new kinds of online platforms as disruptive recordkeeping containers, activists could leave behind external ownership or custodianship by groups outside of their community. In the current scenario, activists have control to retain evidence in the short-term – but the ability to keep records for the long term is a risk that needs active mitigation through ongoing appraisal. The power and autonomy in these actions can be mapped to the RRCM. These appraisal steps for radical recordkeeping are explored in new ways in the following chapter.

Fig. 8.4 Ask Whole Foods a question – get sent to jail.[15]

Figure 8.4 is an example of an activist being arrested at a Whole Foods supermarket in Colorado, for asking challenging questions at the deli counter. In this video, the narrative highlights injustice, inequity and charges for asking simple questions about hidden truths. These hidden truths are protected by ag-gag’s anticipatory witnessing – preventing the average person from entering or recording factory farms without risk of significant jail time and sentencing as an eco-terrorist. The police are used as a prevention for DxE collecting evidence of Whole Foods promoting and selling allegedly mislabelled products. The video production by DxE is an act of strategic witnessing – one that uncovers and disrupts the expectation that consumers can trust their foods are honestly labelled and adequately regulated. With DxE expecting retaliation by Whole Foods, some selective counternarratives (or sense-making) is involved. For example, deciding on the direct action and recording that video, then sharing on YouTube and Facebook platforms, is the pluralisation of that message. The unjust charges of DxE “threatening bodily injury” when the content recorded in this video is clearly a peaceful question to the deli counter staff is disarming to YouTube viewers whose status quo is to believe that police and lawmakers are in place to support a just and fair society.

Through these examples above, the value of records over time are observed, beyond the short-term impact of disruption. By documenting police activity and societal injustice, DxE can potentially reach new audiences beyond the animal rights movement and influence the actions and techniques of other movements facing the same retaliation for their activities.

Counternarratives and (Micro)Aggressions

DxE’s evidence over time drives change through witnessing and uncovering hidden truths with counternarratives. Traces have the potential to be identified as counternarratives or can develop that over time. Power by overt and covert aggression toward DxE (highlighted by the shadow axis) hinder the ability to record these truths and pluralise them into collective memory. Just as the (Trans)actionality axis of activism has dual perspectives in Figure 8.2, with different perspectives of DxE’s activism viewed as irreconcilable ontologies, so too is a dual and conflicting shadow axis demonstrated on the Radical Recordkeeping Continuum Model. An overt example of aggression is exemplified by the Whole Foods vignette. This arrest is particularly aggressive because the allegations of activist violence are seemingly unfounded and malicious.

DxE’s counternarratives are elemental to their engagement with current and potential members. The caring video (Figure 8.5 below) of rescuers rehoming animals is a moving example to future allies and motivates existing volunteers: to reinforce that their activism is a worthwhile cause.

Fig. 8.5 Open Rescue Video by DxE.[16]

The above example of an open rescue video online, makes reference to the emotional bonds of motherly instinct and appeals to those with pets, enabling identification with the nurturing nature of DxE volunteers and motivate others to support the cause. Interestingly, alt text used for accessibility purposes has been automatically applied to the above image during the capture and recapture stages of recreating and republishing this record. The alt text reads: “A person holding a dog. Description automatically generated with low confidence”.[17] This automated tagging is applied to help the visually impaired but is misleading. It is an unintended microaggression distancing farm animals from cared-for pets. The ingrained bias of humans hugging dogs rather than pigs is a socially embedded one that is an example of ongoing systemic change needed in human attitudes, emotions toward animals and systems that rectify and acknowledge these nuances is important. This inherent bias is part of the many societal microaggressions towards animal activists. Other instances can be found in both media representation of DxE and threats made to activists online. The term (micro)aggressions is used in the RRCM to include both micro (unintentional, small or ingrained biases) and overt aggression.

Representing Conflicting Worldviews in an Archival Multiverse

The RCM’s identity axis represents multiple identities of one or more people and entities performing recordkeeping over time. A multiverse can be considered ‘worlds within worlds’ with various worldviews of individuals and groups. This view mirrors the disjointed yet interconnected digital bundles of identity across platforms. To date, Records Continuum Theory has acknowledged the idea of the multiverse, but the oneness of nature and non-violence and rejection of western civilisation as the apex of all modernity is particularly poignant for this DxE study. Since multiple and conflicting ontologies can be mapped with a multiverse in mind, where there is

… a ‘world of many worlds’, that values diversity, autonomy, oneness with nature, nonhierarchy and non-violence.[18]

DxE’s ambient functions and purposes align neatly with Masaki’s philosophical description for respecting equality and non-violence through multiplicity. All radical recordkeepers in this study promote the same values as described above. The power struggle and multiple actors across the social movement for animal rights and the shadow axis is not meant as a neat dualism. There is difficulty in modelling this though and how best to represent blurring between two opposing parts of the same axis. Different and contrasting worldviews are represented, but the continuum model is not about binaries. The relationality is the point of the RRMC “where different worlds are entangled with each other”.[19]

A non-dualist stance that cultivates relationality is needed to examine how transformative initiatives are enacted in concrete practices in sites where different worlds are entangled with each other.[20]

This entanglement is expressed in the RRCM, where each axis could be a helix-shaped one linked to all the other axes across the model. Relational complexity in today’s anthropocene has been described as problematic. Contemporary thinkers, artists, activists, poets, policymakers and others argue that modern frameworks, which attempt to separate humans from nature and view the world as a controllable object, are part of the problem, not the solution[21]. In the Anthropocene, the rich and complex relational entanglements are too vibrant to be managed in this outdated manner.[22] Consequently, the issue of ‘relational entanglements’ has become a central concern in contemporary thought.[23]

Records Continuum Theory can help to represent these entangled worldviews and the conflict between simplistic anthropocentric control of animal activists. Other layers of societal pressure and microaggressions are extant in appraisal in particular.[24] These appraisal complexities can be accounted for in continuum modelling (see the following chapter). There are plural ‘worlds within worlds’ specific to activist groups creating traces in the restrictive anthropocene. The restrictions on recordkeeping in radical ways are important to consider in their dynamic context across a multiverse within the anthropocentric world. How these worlds combine and work in opposition to each other is imagined using the witnessing axis in the RRCM.

The performativity of recordkeeping is described in continuum literature typically as taking place across an archival multiverse across time and space. However, there are yet to be expressions of multiple multiverses or worlds within worlds, such as shadow universes of power that affect appraisal and documentary processes in the continuum. In the archival literature, different models of the RCM for different worldviews have been created separately, but are yet to come together and examined in a combined model. Asynchronous bundles of activity can be deconstructed in analysis of radical recordkeeping on the RRCM. These analyses are merely an ‘archival sliver’[25] but can be nuanced and layered to provide interconnected details to layers of action in society.

Conclusion

The above modelling, analysis and examples of DxE’s radical records show the complexity, multiple perspectives and points of view for interpretation of recordkeeping and power struggles for DxE’s counternarratives. Individuals and groups are making decisions in the ‘doing’ of activism and are maintaining and proliferating records and actions over time, over various media. Modelling as an analytical tool provides insight into risk, challenges and performance of activists in the context of the strategic witnessing and function within an ambient social movement. Modelling can also elucidate automated decision-making by systems and big tech to delete or shadow ban activism online. It also shows the power of social media to be a leveller against misleading information, however, there are downsides and risks to using these platforms.

Modelling was used as an analytical tool to understand the risk, challenges and performance of DxE in the context of its strategic witnessing and role in a social movement. The Radical Recordkeeping Records Continuum Model is introduced as an enhancement to the existing Records Continuum Model, providing insight into the socio-political context of animal activism. The RRCM lays the foundation for a deeper understanding of risk and appraisal tools for animal rights. The next chapter builds upon this analysis to create a continuum-based appraisal model and template for use in practice.

- Leisa Gibbons uses a cone shape for her Mediated Recordkeeping: Culture-as-evidence model with double-sided axes to show fluidity and interconnectivity across all RCM axes. The same shape model is applied here to the RCM for radical recordkeeping (the RRCM). See: Gibbons, Leisa. 2016. “Modelling the Continuum” in Always Becoming Symposium, September 16, 2015. Monash University Melbourne Australia: YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elQGoWMXpJI & Gibbons, Leisa. 2017. “Exploring Social Complexity: Continuum Theory and a Research Design Model for Archival Research.” In Research in the Archival Multiverse. Victoria, Australia: Monash University Publishing. ↵

- see for example: Direct Action Everywhere. 2018. “BACK IN COURT: Where Activists Could Have to Pay $270,000 for Rescuing Two Sick Hens.” Direct Action Everywhere Facebook Page. July 24, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/directactioneverywhere. ↵

- The jury may only receive a narrow re-telling of the story. The injustice of DxE’s video being banned from court is highlighted as a microcosm of the social paradigms and prosecutorial aggressions that reinforce power against activist testimony (See: Lennard, Natasha. 2022. “Prosecutors Silence Evidence of Animal Cruelty in Court.” The Intercept, January 30, 2022. https://theintercept.com/2022/01/30/animal-rights-activists-dxe-trial-evidence/?utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=theintercept&utm_medium=social.). ↵

- Marshall, Catherine C. 2008. “Rethinking Personal Digital Archiving, Part 1.” D-Lib Magazine, 14 (3/4). ↵

- Reed, B., Upward, F., Oliver, G., & Jarvie, K. (2016). Recordkeeping Informatics: An Introduction for the purposes of education and training. Congress Workshops. Presented at the International Council on Archives Congress, South Korea. Retrieved from https://www.ica.org/en/congress-workshops ↵

- Upward, Frank, Gillian Oliver, Barbara Reed and Joanne Evans. 2017. Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Clayton Vic Australia: Monash University Publishing. p. ix. ↵

- Upward, Frank. 2005. “Continuum Mechanics and Memory Banks [Series of Two Parts] Part 2: The Making of Culture.” Archives and Manuscripts 33 (2): 18–51. ↵

- Kaye, David, Rasha Abdulla, Mohamad Najem, Marwa Fatafta and Dia Kayyali. 2022. “Platform Content Moderation in the Arab World: An Update.” In RightsCon summit by AccessNow. ↵

- Fowler, Geoffrey A. 2022. “Shadowbanning Is Real: Here’s How You End up Muted by Social Media.” The Washington Post , December 28, 2022. ↵

- Akkad, Dania. 2019. “Egyptian Activists Sound Alarm over Twitter Account Suspensions.” Middle East Eye, October 1, 2019. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/egyptian-activists-sound-alarm-over-twitter-account-suspensions. ↵

- Kirby, Natalie and Salvatore Romano. 2022. “Tracking Exposed: A Tool for TikTok Algorithmic Audits and Cross-National Comparisons.” In RightsCon Summit by AccessNow. https://rightscon.summit.tc/t/2022/events/agenda?view=agenda&tab=my-events. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2015. “Culture in the Continuum: YouTube, Small Stories and Memory-Making.” Doctoral dissertation, Monash University. Faculty of Information Technology. Caulfield School of Information Technology. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2015. “Continuum Informatics and the Emergent Archive.” In Community Informatics Research Network (CIRN) Conference, Prato: Monash University. p.10. ↵

- Gibbons, Leisa. 2017. “Use of Personal Reflexive Modelling in Challenging Conceptualisations of Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (8): 1–14. ↵

- Direct Action Everywhere. (Used with Permission). 2018. Ask Whole Foods a question. Get sent to jail. It happened to Wayne Hsiung. YouTube Video. ↵

- Direct Action Everywhere. (Used with permission). 2016. Piglet finds a new Mom. YouTube Video. ↵

- Quoted from the MS Word draft of my thesis 23/6/2021, available at Jarvie, Katherine. 2023. “Radical Recordkeeping — Re-Thinking Archival Appraisal.” Monash University. ↵

- Masaki, Katsu. 2021. “Do Pluriversal Arguments Lead to a ‘World of Many Worlds’? Beyond the Confines of (Anti-)Modern Certainties.” SSRN Electronic Journal. p.2. ↵

- Masaki, Katsu. 2021. “Do Pluriversal Arguments Lead to a ‘World of Many Worlds’? Beyond the Confines of (Anti-)Modern Certainties.” SSRN Electronic Journal. p.4. ↵

- Masaki, Katsu. 2021. “Do Pluriversal Arguments Lead to a ‘World of Many Worlds’? Beyond the Confines of (Anti-)Modern Certainties.” SSRN Electronic Journal. p.2. ↵

- e.g. Latour, Bruno. 2017. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity. & Yusoff K. (2018) A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ↵

- Alaimo, Stacy. 2016. Exposed: Environmental Politics & Pleasures in Posthuman Times. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. & Haraway D. J. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ↵

- Pugh, Jonathan and David Chandler. 2021. Anthropocene Islands: Entangled Worlds. University of Westminster Press. ↵

- Dunbar, Anthony W. 2006. “Introducing Critical Race Theory to Archival Discourse: Getting the Conversation Started.” Archival Science 6 (1): 109–29. ↵

- Harris, Verne. 2002. “The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory and Archives in South Africa.” Archival Science, 2 (1–2): 63–86. ↵

Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1996) are complementary frames for addressing societal grand challenges such as social justice imperatives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106). This framing is described here as critical continuum research. A community of academics and educators are

… going beyond the apparent to reveal hidden agendas, concealed inequalities and tacit manipulation (Evans et al., 2017, 2) …

to explore multidimensional accounts of archives and recordkeeping and question societal dynamics for a fairer world. Continuum scholars seek to reveal established power and exclusion in an archival multiverse (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). The archival multiverse is a “plurality of evidentiary texts: developed by a person, community or group for memory-keeping” (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2012, 106-7). To ensure equitable societal representation, continuum research progresses analysis of practices beyond narrow and exclusionary archival narratives and systems in institutional and collecting archives (Gilliland & McKemmish, 2014). Records Continuum Theory and the Records Continuum Model (Upward, 1997) provide a foundation for exploring societal functions in a multitude of ways and contexts.

References

Evans, Joanne, Sue McKemmish and Greg Rolan. 2017. “Critical Approaches to Archiving and Recordkeeping in the Continuum.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1 (2): 1–38.

Gilliland, Anne, and Sue McKemmish. 2012. “Recordkeeping Metadata, the Archival Multiverse, and Societal Grand Challenges.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Kuching Sarawak, 3–7 September 2012.

Gilliland, Anne and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice, 24: 79–88.

Upward, Frank. 1997. “Structuring the Records Continuum (Series of Two Parts) Part 2: Structuration Theory and Recordkeeping.” Archives and Manuscripts, 25 (1): 10–35.

The Pluralising the Archival Curriculum Group, which was made up of a large number of international scholars engaged in AERI [Archival Education Reseach Institutes]. They define the archival multiverse as "... encompassing

the pluralism of evidentiary texts, memory-keeping practices and institutions, bureaucratic and personal motivations, community perspectives and needs, and cultural and legal constructs with which archival professionals and academics must be prepared, through graduate education, to engage."

McKemmish, Sue, and Michael Piggott. 2013. “Toward the Archival Multiverse: Challenging the Binary Opposition of the Personal and Corporate Archive in Modern Archival Theory and Practice.” Archivaria. 76, p. 113.

"Ambience is the context of provenance ... Functions offer one possible tool for crafting ambient relationships. Ambient functions define and give meaning to agents of record-keeping within the context in which they operate."

Hurley, Chris. 1995. “Ambient Functions - Abandoned Children to Zoos.” Archivaria 40 (June): 21–39.

One example of this ambience is having a shared context of animal liberation activism. Chris Hurley’s multiple simultaneous provenances are occurring at a group level for activist group Direct Action Everywhere (DxE), but individuals and the broader movement are also co-creators and stakeholders in DxE records (at an ambient level). Hurley’s description of ambience can also be applied in the animal activism context for ambient identity and ambient purposes.

Instantaneous archiving, usually online and using technology to create, capture, organise and pluralise records (continuum-style), often concurrently. "Nanosecond archiving is a modern reality. It is not its existence that is in question in this book, only its quality."

Upward, Frank, Barbara Reed, Gillean Oliver, and Joanne Evans. 2017. “Chapter 2. A History of the Recordkeeping Single Mind, 1915–2015.” In Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Victoria: Monash University ePress.

The term ‘platform’ is used in this book the way Terri Lee Harel, Muira McCammon and Jessa Lingel refer to them as a discrete but interconnected online space. A digital platform is an online framework or infrastructure that enables the creation, exchange, and consumption of digital content, services, or products. It provides the technological foundation for interactions among users, businesses, and applications, facilitating activities such as communication, commerce, information sharing, and collaboration. Digital platforms often leverage cloud computing, data analytics, and network connectivity to support and enhance these interactions, and can include social media sites, e-commerce marketplaces, content streaming services, and software development environments.

Platforms are also considered here “emergent archival spaces” as defined by Leisa Gibbons.

References

Harel, Terri Lee. 2022. "Archives in the Making: Documenting the January 6 capitol riot on Reddit". Internet Histories, 6(4), 1–21.

McCammon, Muira & Jessa Lingel. 2022. "Situating Dead-and-dying Platforms: Technological failure, infrastructural precarity, and digital decline". Internet Histories, 6(1–2), 1–13.

Gibbons, Leisa. 2020. "Community Archives in Australia: A preliminary investigation. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(4), 1–22.

In the context of networked communities, a digital bundle refers to a cohesive and interconnected collection of records and information shared and distributed across various online platforms and social media channels.

Jennifer Wemwigans uses the term in the context of Indigenous community knowledge and teachings.

Wemwigans, J. 2021. Keynote: Dr. Jennifer Wemigwans – AERI. Presented at the Archival Education and Research Initiative online conference. Online, July 13.

..." a framework through which we can think about the politics of media witnessing as dependent upon audience differentiation, which activists utilize as a tactical apparatus geared toward social change."

Ristovska, Sandra. 2016. “Strategic Witnessing in an Age of Video Activism.” Media, Culture and Society, 38 (7): 1034–37.

"...the Kantian notion of autonomy consists in the capacity to step back from any inclination or desire one might have, including those inculcated in us by our upbringing, and engage in reasoning about whether they ought to be followed. Unlike other beings known to us, humans can stand back from our motivations and subject them to rational scrutiny and freely decide in light of that assessment how to act. This capacity is the source of a special dignity that inheres in all human beings."

Dogas, Christos. 2021. “AI, Freedom of Choice, Aristotle and Kant.” OT / Οικονομικός Ταχυδρόμος - Ot.Gr, December 4, 2021. https://www.ot.gr/2021/12/04/english-edition/ai-freedom-of-choice-aristotle-and-kant/.

" ... radical agents become [so] ... by acting in excess of their ‘proper’ place – laying claim to rights and values that have historically been inaccessible from that position."

Feola, Michael. 2019. “Excess Words, Surplus Names: Rancière and Habermas on Speech, Agency, and Equality.” Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy, 27 (2): 32–53.

"From the political left, scholarship has focused attention on the potential of social movements as autonomous agents of urban transformation, promoting radical democratisation and social justice ‘outside’ and against the coercive logics of the capitalist state".

Inch, Andy, J Slade, S Brownill, G Ellis, M Howcroft, D Humphry, L Leeson, G O’Hara, F Sartorio, and G Robbins. 2024. “Community Action, Counter-Professionals and Radical Planning in the UK.” City, 28 (5–6): 681–704.

"... legislation that prohibits covert documentation or investigation of conditions in the farming industry (used chiefly by opponents of such legislation)”.

Oxford University Press. 2019. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/ (accessed 2019)

Muira McCammon describes this control as limiting what is seen and who sees it, by authorities in controlled spaces. Here the idea is expanded to a definition for distrust of surveillance online.

McCammon, Muira. “Anticipatory witnessing: military bases and the politics of pre-empting access.” Information, Communication & Society, 25, no. 7 (September 2020): 1–17.

When multiple ontologies are irreconcilable, it means that the differences in these frameworks are so significant that they cannot be harmonised or unified. This can create challenges in managing, accessing, and interpreting archival materials, as different stakeholders may have conflicting views on how the information should be organised and understood.

See Hurley, Chris. 2005. “Parallel Provenance (If These Are Your Records, Where Are Your Stories?).” Archives and Manuscripts, 33 (1 & 2).