2.5 The Cell Membrane

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the fluid mosaic model of membranes

- Describe the functions of phospholipids, proteins, and carbohydrates in membranes

A cell’s plasma membrane defines the boundary of the cell and determines the nature of its contact with the environment. Cells exclude some substances, take in others, and excrete still others, all in controlled quantities. Plasma membranes enclose the borders of cells, but rather than being a static bag, they are dynamic. The plasma membrane must be sufficiently flexible to allow certain molecules. These are the more obvious functions of a plasma membrane. In addition, the surface of the plasma membrane carries markers that allow cells to recognise one another, which is vital as tissues and organs form during early development, and which later plays a role in the “self” versus “non-self” distinction of the immune response.

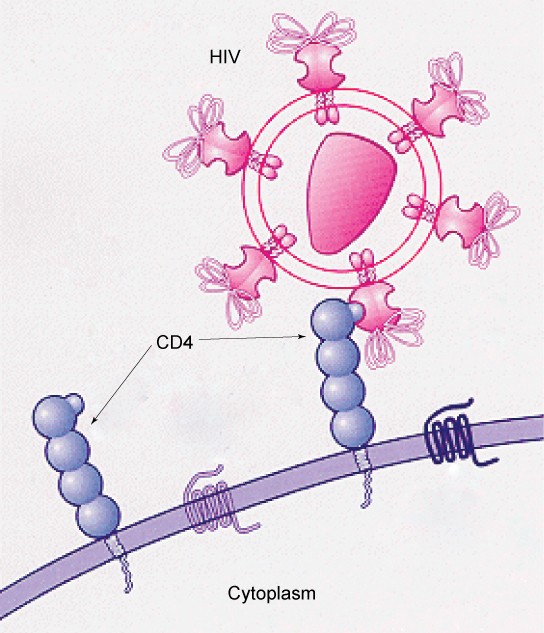

The plasma membrane also carries receptors, which are attachment sites for specific substances that interact with the cell. Each receptor is structured to bind with a specific substance. For example, surface receptors of the membrane create changes in the interior, such as changes in enzymes of metabolic pathways. These metabolic pathways might be vital for providing the cell with energy, making specific substances for the cell, or breaking down cellular waste or toxins for disposal. Receptors on the plasma membrane’s exterior surface interact with hormones or neurotransmitters, and allow their messages to be transmitted into the cell. Some recognition sites are used by viruses as attachment points. Although they are highly specific, pathogens like viruses may evolve to exploit receptors to gain entry to a cell by mimicking the specific substance that the receptor is meant to bind. This specificity helps to explain why human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or any of the five types of hepatitis viruses invade only specific cells.

Fluid Mosaic Model

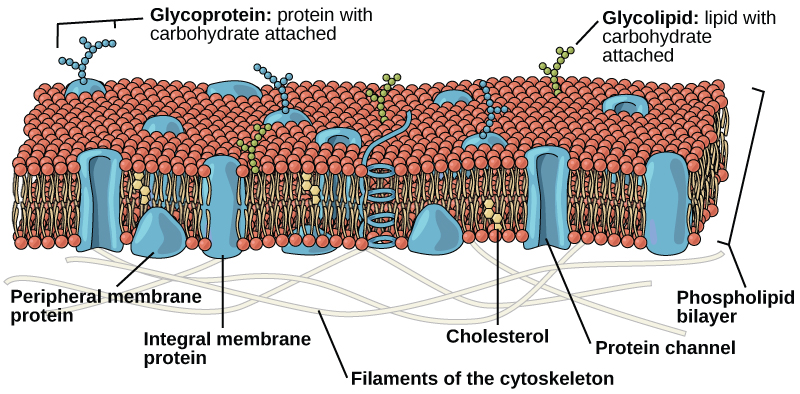

In 1972, S. J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson proposed a new model of the plasma membrane that, compared to earlier understanding, better explained both microscopic observations and the function of the plasma membrane. This was called the fluid mosaic model. The model has evolved somewhat over time, but still best accounts for the structure and functions of the plasma membrane as we now understand them. The fluid mosaic model describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components—including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates—in which the components are able to flow and change position while maintaining the basic integrity of the membrane. Both phospholipid molecules and embedded proteins are able to diffuse rapidly and laterally in the membrane. The fluidity of the plasma membrane is necessary for the activities of certain enzymes and transport molecules within the membrane. Plasma membranes range from 5–10 nm thick. As a comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm thick, or approximately 1,000 times thicker than a plasma membrane.

The plasma membrane is made up primarily of a bilayer of phospholipids with embedded proteins, carbohydrates, glycolipids, glycoproteins, and, in animal cells, cholesterol. The amount of cholesterol in animal plasma membranes regulates the fluidity of the membrane and changes based on the temperature of the cell’s environment. In other words, cholesterol acts as antifreeze in the cell membrane and is more abundant in animals that live in cold climates.

Membrane Lipids

Phospholipids

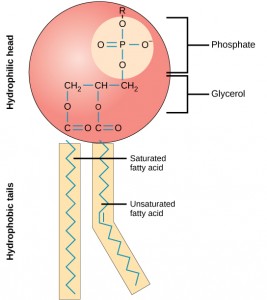

The main fabric of the membrane is composed of two layers of phospholipid molecules, and the polar ends of these molecules (which look like a collection of balls in an artist’s rendition of the model) (Figure 2.5.2) are in contact with aqueous fluid both inside and outside the cell. Thus, both surfaces of the plasma membrane are hydrophilic. In contrast, the interior of the membrane, between its two surfaces, is a hydrophobic or nonpolar region because of the fatty acid tails. This region has no attraction for water or other polar molecules.

The structure of a phospholipid molecule includes a glycerol or sphingosine backbone. Glycerol is a three-carbon alcohol molecule, while sphingosine is a derivative of the amino acid serine with a fatty acid attached. Phospholipids with a glycerol backbone are known as phosphoglycerolipids or phosphoglycerides, while those with a sphingosine backbone are called phosphosphingolipids.

Attached to this backbone are two nonpolar fatty acid chains and a negatively charged phosphate molecule. The phosphate group is polar due to its negative charge and often has a charged or polar head group attached, such as choline. This forms the hydrophilic “head” of the phospholipid.

On the other hand, the fatty acid chains are nonpolar and form the hydrophobic “tails” of the phospholipid. These tails are repelled by water and prefer to interact with other nonpolar substances.

This amphipathic nature of phospholipids is crucial for their role in the plasma membrane. The hydrophobic tails align towards each other, forming the interior of the membrane, while the hydrophilic heads face outwards, interacting with the aqueous environment found both inside and outside the cell. This arrangement forms a stable barrier between the cell and its environment, while also allowing for selective permeability of certain substances.

Glycolipids

Glycolipids are composed of a lipid molecule that has one or more carbohydrate molecules attached to it. This combination of lipids and carbohydrates gives glycolipids unique properties that are crucial for their role in the cell membrane.

Like phospholipids, glycolipids can have either a glycerol backbone or a sphingosine backbone. Glycolipids with a glycerol backbone are known as glycoglycerolipids, while those with a sphingosine backbone are called glycosphingolipids.

One of the key characteristics of glycolipids is that they are found exclusively on the outer surface of the plasma membrane. This is because the carbohydrate portion of the glycolipid molecule is hydrophilic (water-loving), and so it is oriented towards the aqueous environment outside the cell.

Glycolipids play several important roles in cellular function. They are involved in cell communication and recognition, as the carbohydrate portion of the glycolipid can interact with other molecules and cells. This can be crucial for processes such as immune response, where cells need to be able to recognise and respond to foreign substances.

Glycolipids also protect the cell. The carbohydrate groups can form a protective layer on the cell surface, helping to shield the cell from mechanical and chemical damage. This protective layer is called Glycocalyx.

Sterols

Sterols are a type of lipid present in the cell membranes of most eukaryotic cells. They are characterised by a structure that includes a hydrocarbon ring and a hydroxyl group. This structure gives sterols their amphipathic properties, meaning they have both hydrophilic (water-loving) and hydrophobic (water-fearing) regions.

The most well-known sterol is cholesterol, which is the main sterol found in animal cells. Cholesterol is a four-ring amphipathic molecule, with the hydroxyl group forming the polar “head” and the hydrocarbon rings and tail forming the nonpolar “tail”.

Cholesterol plays a crucial role in maintaining the fluidity and stability of cell membranes. It fits between the fatty acid chains of phospholipids, filling the spaces left by kinks in the chains. This prevents fatty acid chains from packing together and crystallising, thereby maintaining the fluidity of the membrane.

At the same time, the presence of cholesterol restricts the movement of the fatty acid chains, which helps to stabilise the membrane and prevent it from becoming too fluid. This balance helps to ensure that the membrane remains flexible yet strong, allowing it to fulfil its role as a protective barrier for the cell.

Membrane Proteins

Proteins are the second major chemical component of plasma membranes. Membrane proteins can be classified as integral membrane proteins, peripheral membrane proteins, and lipid-anchored proteins.

Integral Membrane Proteins

Integral proteins are embedded in the plasma membrane and may span all or part of the membrane. Integral proteins may serve as channels or pumps to move materials into or out of the cell.

Integral membrane proteins are tightly attached to or associated with the cell membrane. They have both hydrophilic (water-loving) and hydrophobic (water-fearing) regions, which makes them amphipathic. This characteristic allows them to interact with both the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane and the aqueous environment inside and outside the cell.

The hydrophobic regions of integral membrane proteins are typically composed of nonpolar amino acids. These regions interact with the hydrophobic interior of the lipid bilayer, allowing the protein to be embedded within the membrane. This is often facilitated by alpha-helices or beta-barrels, which are common structural motifs in integral membrane proteins that can span the lipid bilayer.

The hydrophilic regions of integral membrane proteins, on the other hand, are typically composed of polar amino acids. These regions interact with the aqueous environment inside and outside the cell, allowing the protein to extend out from the membrane. These regions can be found on either side of the membrane, depending on the specific protein and its function.

Integral membrane proteins play a wide variety of roles in cellular function. They can act as channels or transporters, allowing specific substances to move across the cell membrane. They can also function as receptors, binding to specific molecules and triggering cellular responses. Additionally, they can serve as enzymes, catalysing specific chemical reactions at the cell membrane.

Peripheral Membrane Proteins

Peripheral membrane proteins, also known as extrinsic proteins, are proteins that are loosely attached to the cell membrane. Unlike integral membrane proteins, which are embedded within the lipid bilayer, peripheral proteins are located on the membrane’s exterior (extracellular) or interior (intracellular) surfaces.

These proteins are typically attached to either integral membrane proteins or to the polar heads of phospholipid molecules. They do not penetrate the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer, which distinguishes them from integral proteins.

Peripheral membrane proteins play a variety of roles in cellular function. One of their key roles is providing structural support to the cell. They can connect the cytoskeleton, which is a network of protein filaments inside the cell that helps maintain the cell’s shape, to the extracellular matrix, which is a network of proteins and carbohydrates outside the cell that provides structural and biochemical support to the cell.

In addition to their structural roles, peripheral proteins can also carry out enzyme activities, catalysing specific chemical reactions at the cell membrane. They can also be involved in cell communication, transmitting signals from the cell’s environment to the inside of the cell.

The interaction of peripheral proteins with the cell membrane is typically via weak electrostatic forces and hydrogen bonds. This means that they can be easily separated from the membrane by changes in conditions such as pH or ionic strength, which can disrupt these weak interactions.

Lipid Anchored Proteins

Lipid-anchored proteins are a type of protein that are attached to the cell membrane via a lipid molecule. These proteins are covalently (permanently) attached to lipid molecules such as glycosphingolipids, which are a type of sphingolipid with one or more sugar molecules attached. This attachment allows the protein to be anchored to the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane, hence the name “lipid-anchored proteins”.

Lipid rafts are specialised microdomains within the cell membrane that are enriched in certain types of lipids, such as sphingolipids and cholesterol, as well as lipid-anchored proteins. These rafts are thought to be more ordered and tightly packed than the surrounding membrane, due to the longer fatty acid chains of sphingolipids and the rigid structure of cholesterol.

Because of this, lipid rafts are often slightly thicker or “raised out” compared to the surrounding membrane. They are typically found on the outer surface of the cell membrane, although they can also be present on the inner surface.

Lipid rafts play several important roles in cellular function. One of their key roles is in cell signalling. Many signalling proteins are found within lipid rafts, and the rafts can serve as platforms for these proteins to interact and transmit signals. By concentrating signalling molecules in one place, lipid rafts can enhance the efficiency and specificity of cellular signalling processes.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are the third major component of plasma membranes. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids). These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2–60 monosaccharide units and may be either straight or branched. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other.

Evolution Connection

How Viruses Infect Specific Organs? Specific glycoprotein molecules exposed on the surface of the cell membranes of host cells are exploited by many viruses to infect specific organs. For example, HIV is able to penetrate the plasma membranes of specific kinds of white blood cells called T-helper cells and monocytes, as well as some cells of the central nervous system. The hepatitis virus attacks only liver cells.

These viruses are able to invade these cells, because the cells have binding sites on their surfaces that the viruses have exploited with equally specific glycoproteins in their coats. (Figure 2.5.3). The cell is tricked by the mimicry of the virus coat molecules, and the virus is able to enter the cell. Other recognition sites on the virus’s surface interact with the human immune system, prompting the body to produce antibodies. Antibodies are made in response to the antigens (or proteins associated with invasive pathogens). These same sites serve as places for antibodies to attach, and either destroy or inhibit the activity of the virus. Unfortunately, these sites on HIV are encoded by genes that change quickly, making the production of an effective vaccine against the virus very difficult. The virus population within an infected individual quickly evolves through mutation into different populations, or variants, distinguished by differences in these recognition sites. This rapid change of viral surface markers decreases the effectiveness of the person’s immune system in attacking the virus, because the antibodies will not recognize the new variations of the surface patterns.

Practice Questions

Section Summary

- The modern understanding of the plasma membrane is referred to as the fluid mosaic model.

- The plasma membrane is composed of a bilayer of phospholipids, with their hydrophobic, fatty acid tails in contact with each other. The landscape of the membrane is studded with proteins, some of which span the membrane. Some of these proteins serve to transport materials into or out of the cell.

- Carbohydrates are attached to some of the proteins and lipids on the outward-facing surface of the membrane. These form complexes that function to identify the cell to other cells. The fluid nature of the membrane owes itself to the configuration of the fatty acid tails, the presence of cholesterol embedded in the membrane (in animal cells), and the mosaic nature of the proteins and protein-carbohydrate complexes, which are not firmly fixed in place.

- Plasma membranes enclose the borders of cells, but rather than being a static bag, they are dynamic and constantly in flux.

Glossary

fluid mosaic model: a model of the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components, including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and glycolipids, resulting in a fluid rather than static character.