6.1 Energy and Metabolism

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what metabolic pathways are

- State the first and second laws of thermodynamics

- Explain the difference between kinetic and potential energy

- Describe endergonic and exergonic reactions

- Discuss how enzymes function as molecular catalysts

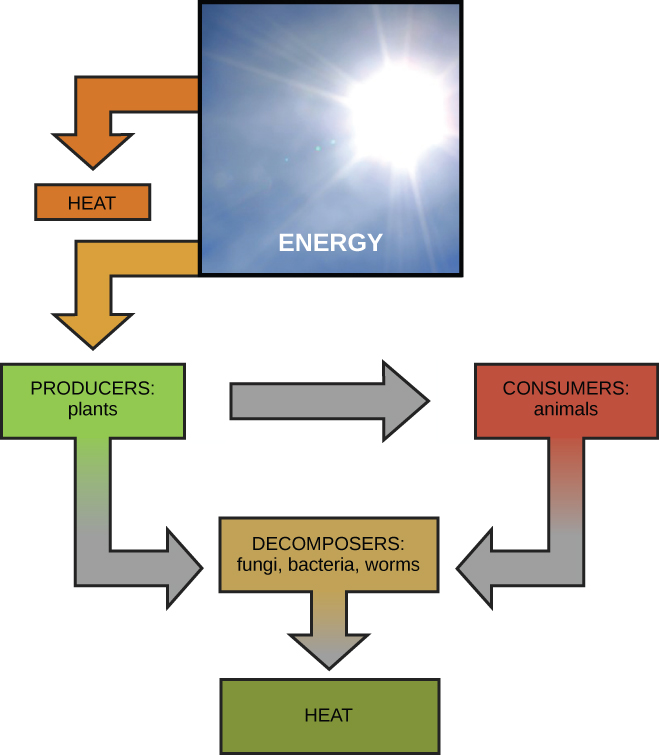

Scientists use the term bioenergetics to describe the concept of energy flow (Figure 6.1.1) through living systems, such as cells. Cellular processes such as the building and breaking down of complex molecules occur through stepwise chemical reactions. Metabolism refers to all of the chemical reactions that take place inside a cell/organism, including those reactions that consume (anabolism) or generate energy (catabolism).

Metabolic Pathways

Consider the metabolism of glucose. Nearly all living organisms consume glucose as a major energy source, as this molecule has a lot of energy stored within its bonds. During the process of photosynthesis, plants use energy (originally from sunlight) to convert carbon dioxide (CO2) into glucose (C6H12O6), and other carbohydrates. The overall reaction for photosynthesis s best summarised by the following reaction step [1].

6CO2 + 6H2O + energy ——-> C6H12O6 + 6O2 [1]

Photosynthesis consists of two major phases – (a) the light dependent reactions and (b) the light-independent reactions (dark reactions). During the first phase, energy is provided by a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is used as a means to transfer energy between chemical reactions occurring within a cell. In the formation of large molecules in the cell much energy is needed to create new bonds. Energy-storage molecules such as glucose are broken down to liberate the energy that is in their bonds. Of interest is that the breakdown of glucose to CO2 and H2O is the reverse of glucose formation in that energy is released. This reaction can be seen in the following reaction step [2].

C6H12O6 + 6O2 ——> 6CO2 + 6H2O + energy [2]

Please note that both reaction step 1 and 2 represent many individual reaction steps.

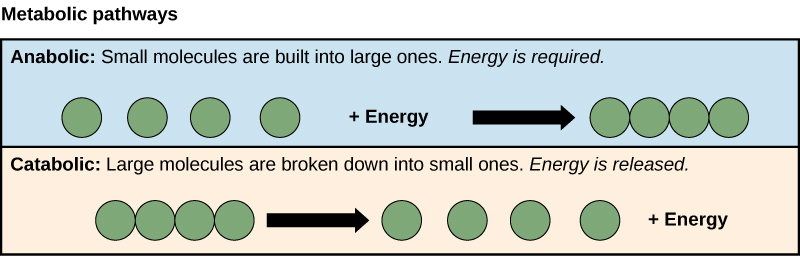

The processes of making and breaking down glucose molecules illustrate two examples of metabolic pathways. A metabolic pathway is a series of chemical reactions that takes a starting molecule and modifies it, step-by-step, through a series of metabolic intermediates, eventually yielding a final product. In the example of glucose metabolism, the first metabolic pathway synthesized glucose from smaller molecules, and the other pathway broke sugar down into smaller molecules. These two opposite processes—the first requiring energy and the second producing energy—are referred to as anabolic pathways (building polymers) and catabolic pathways (breaking down polymers into their monomers), respectively. Consequently, metabolism is composed of synthesis (anabolism) and degradation (catabolism) (Figure 6.1.2).

You should note that the chemical reactions occurring in metabolic pathways do not take place on their own. Each reaction step is catalysed, by enzymes. Most enzymes found in nature are proteins though some are RNA molecules. Enzymes are important for catalysing all types of biological reactions—irrespective of whether they require or release energy.

Energy

Thermodynamics refers to the study of energy and energy transfer involving physical matter. The matter relevant to a particular case of energy transfer is called a system, and everything outside of that matter is called the surroundings. For instance, when heating a pot of water on the stove, the system includes the stove, the pot, and the water. Energy is transferred within the system (between the stove, pot, and water). There are two types of systems: open and closed. In an open system, energy can be exchanged with its surroundings. The stovetop system is open because heat can be lost to the air. Note that a closed system cannot exchange energy with its surroundings.

Biological organisms are open systems. Energy is exchanged between them and their surroundings. The laws of thermodynamics govern the transfer of energy in and among all systems in the universe including those of biological organisms.

In general, energy is often defined as the ability to do work, or to create some kind of change. It can exist in different forms. For example, electrical energy, light energy, and heat energy are all different types of energy. To appreciate the way energy flows into and out of biological systems, it is important to understand two of the physical laws that govern energy.

Thermodynamics

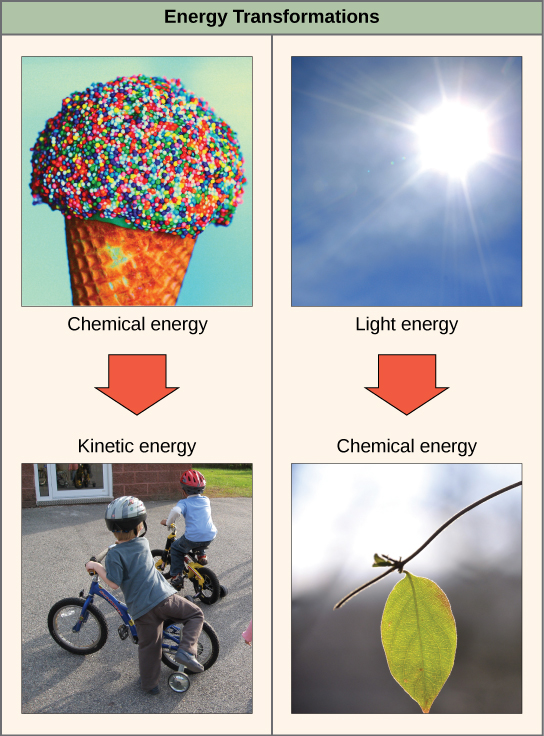

The first law of thermodynamics states that the total amount of energy in the universe is constant and conserved. Energy exists in many different forms. According to the first law of thermodynamics, energy can be transferred from place to place or transformed into different forms, but it cannot be created or destroyed. The transfers and transformations of energy take place around us all the time. Light bulbs transform electrical energy into light and heat energy. Plants convert the energy of sunlight to chemical energy stored within organic molecules e.g. glucose. Some examples of energy transformations are shown in Figure 6.1.3.

Living cells use the chemical energy stored within organic molecules (e.g. sugars and fats) is transferred and transformed through a series of cellular chemical reactions into energy within molecules of ATP. The energy in ATP is easily accessible to do work, such as building complex molecules, transporting materials, powering the motion of cilia or flagella, and contracting muscle fibres to create movement.

A living cell’s primary tasks of obtaining, transforming, and using energy to do work may seem simple. However, the second law of thermodynamics explains why these tasks are harder than they appear. All energy transfers and transformations are never completely efficient, and some energy is lost in a form that is unusable. In most cases, this form is heat energy.

An important aspect of physical systems is that of order and disorder. The more energy that is lost by a system to its surroundings, the less ordered and more random the system is. Scientists refer to the measure of randomness or disorder within a system as entropy. High entropy means high disorder and low energy. Molecules and chemical reactions have varying entropy as well. Living things are highly ordered, requiring constant energy input to be maintained in a state of low entropy.

Potential Energy

On a molecular level, the bonds that hold the atoms of molecules together exist in a particular structure that has potential energy. Potential energy is stored within the bonds of all the food molecules we eat, which is eventually harnessed for use. This is because these bonds can release energy when broken. This type of potential energy that exists within chemical bonds is called chemical energy. Chemical energy is responsible for providing living cells with energy from food which is released when the molecular bonds within food molecules are broken.

Free Energy

How is the energy associated with the chemical reactions occurring in a cell quantified and expressed? How can the energy released from one reaction be compared to that of another reaction?

According to the second law of thermodynamics, all energy transfers involve the loss of some energy in an unusable form such as heat. Free energy specifically refers to the energy associated with a chemical reaction that is available after the losses are accounted for. In other words, free energy is usable energy.

If energy is released during a chemical reaction, then the change in free energy, signified as ∆G (delta G) will be a negative number. A negative change in free energy also means that the products of the reaction have less free energy than the reactants, because they release some free energy during the reaction. Reactions that have a negative change in free energy and consequently release free energy are called exergonic reactions. These reactions are also referred to as spontaneous reactions, and their products have less stored energy than the reactants.

If a chemical reaction absorbs energy rather than releases energy on balance, then the ∆G for that reaction will be a positive value. Here, the products have more free energy than the reactants. Thus, the products of these reactions can be thought of as energy-storing molecules. These chemical reactions are called endergonic reactions, and they are non-spontaneous. An endergonic reaction will not take place on its own without the addition of free energy.

Watch Activation energy and enzymes to highlight the flow of energy when a reaction takes place.

Enzymes

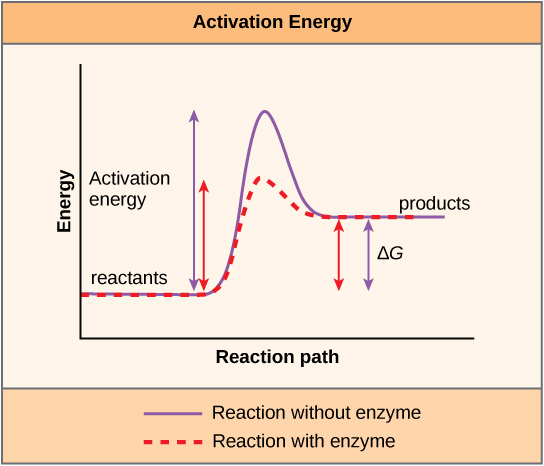

A substance that helps a chemical reaction to occur is called a catalyst, and the molecules that catalyse biochemical reactions are called enzymes. Most enzymes are proteins and perform the critical task of lowering the activation energies of chemical reactions inside the cell, and in doing so speed up the rate of these reactions.

Enzymes bind to the reactant molecules and holding them in such a way as to make the chemical bond-breaking and -forming processes occur more easily. It is important to remember that enzymes do not change whether a reaction is exergonic (spontaneous) or endergonic. This is because they do not change the free energy of the reactants or products. They only reduce the activation energy required for the reaction to go forward (Figure 6.1.4). In addition, an enzyme itself is unchanged by the reaction it catalyses. Once one reaction has been catalysed, the enzyme is able to participate in other reactions.

The chemical reactants to which an enzyme binds are called the enzyme’s substrates. There may be one or more substrates, depending on the particular chemical reaction. The location within the enzyme where the substrate binds is called the enzyme’s active site. Since enzymes are proteins, there is a unique combination of amino acid side chains within the active site. Each side chain is characterized by different properties. They can be large or small, weakly acidic or basic, hydrophilic or hydrophobic, positively or negatively charged, or neutral. The unique combination of side chains creates a very specific chemical environment within the active site. This specific environment is suited to bind to one specific chemical substrate (or substrates).

Active sites are subject to influences of the local environment. Increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme-catalysed or otherwise. However, temperatures outside of an optimal range reduce the rate at which an enzyme catalyses a reaction. Hot temperatures will eventually cause enzymes to denature, an irreversible change in the three-dimensional shape and therefore the function of the enzyme. Enzymes are also suited to function best within a certain pH and salt concentration range, and, as with temperature, extreme pH, and salt concentrations can cause enzymes to denature.

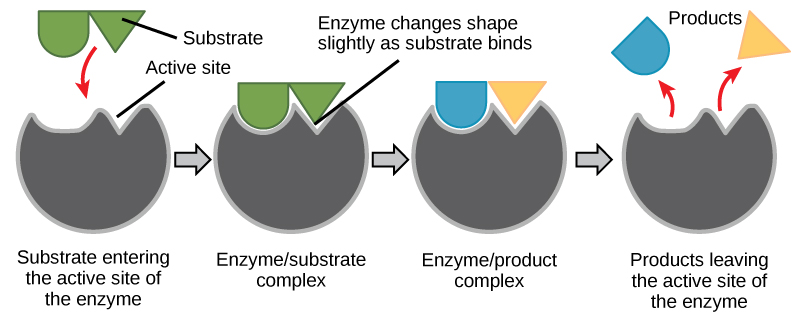

It is unclear if enzyme-substrate binding is via a simple “lock and key” fashion, where the enzyme and substrate fit together perfectly in one instantaneous step. However, current research supports a model called induced fit (Figure 6.1.5). The induced-fit model expands on the lock-and-key model by describing a more dynamic binding between enzyme and substrate. As the enzyme and substrate come together, their interaction causes a mild shift in the enzyme’s structure that forms an ideal binding arrangement between enzyme and substrate.

For more information, please look at the induced fit model of enzyme action.

When an enzyme binds its substrate, an enzyme-substrate complex is formed. This complex lowers the activation energy of the reaction and promotes its rapid progression in one of multiple possible ways. On a basic level, enzymes promote chemical reactions that involve more than one substrate by bringing the substrates together in an optimal orientation for reaction. Another way in which enzymes promote the reaction of their substrates is by creating an optimal environment within the active site for the reaction to occur.

The enzyme-substrate complex can also lower activation energy by compromising the bond structure so that it is easier to break. Finally, enzymes can also lower activation energies by taking part in the chemical reaction itself. In these cases, it is important to remember that the enzyme will always return to its original state by the completion of the reaction. One of the hallmark properties of enzymes is that they remain ultimately unchanged by the reactions they catalyse. After an enzyme has catalyzed a reaction, it releases its product(s) and can catalyse a new reaction.

As the rates of biochemical reactions are controlled by activation energy, and enzymes lower and determine activation energies for chemical reactions, the relative amounts and functioning of the variety of enzymes within a cell ultimately determine which reactions will proceed and at what rates. This determination is tightly controlled in cells. In certain cellular environments, enzyme activity is partly controlled by environmental factors like pH, temperature, salt concentration, and, in some cases, cofactors or coenzymes.

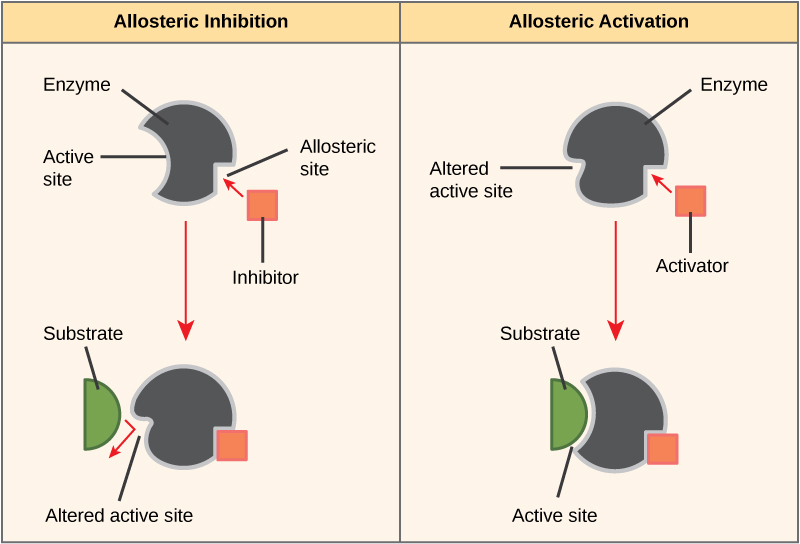

Enzymes can also be regulated in ways that either promote or reduce enzyme activity. There are many kinds of molecules that inhibit or promote enzyme function, and various mechanisms by which they do so. In some cases of enzyme inhibition, an inhibitor molecule is structurally similar to the substrate and can bind to the active site and simply block the substrate from binding. This is called competitive inhibition, because the inhibitor molecule competes with the substrate for binding to the active site.

On the other hand, in noncompetitive inhibition, an inhibitor molecule binds to the enzyme in a location other than the active site, called an allosteric site, but still manages to block substrate binding to the active site. Some inhibitor molecules bind to enzymes in a location where their binding induces a conformational change that reduces the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate. This type of inhibition is called allosteric inhibition (Figure 6.1.6). Most allosterically regulated enzymes are made up of more than one polypeptide, meaning that they have more than one protein subunit. When an allosteric inhibitor binds to a region on an enzyme, all active sites on the protein subunits are changed slightly such that they bind their substrates with less efficiency. There are allosteric activators as well as inhibitors. Allosteric activators bind to locations on an enzyme away from the active site, inducing a conformational change that increases the affinity of the enzyme’s active site(s) for its substrate(s) (Figure 6.1.6).

Many enzymes do not work optimally, or even at all, unless bound to other specific non-protein helper molecules. They may bond either temporarily through ionic or hydrogen bonds, or permanently through stronger covalent bonds. Binding to these molecules promotes optimal shape and function of their respective enzymes. Two examples of these types of helper molecules are cofactors and coenzymes.

Cofactors are inorganic ions such as ions of iron and magnesium. Coenzymes are organic helper molecules, those with a basic atomic structure made up of carbon and hydrogen. Vitamins are the source of coenzymes. Some vitamins are the precursors of coenzymes and others act directly as coenzymes.

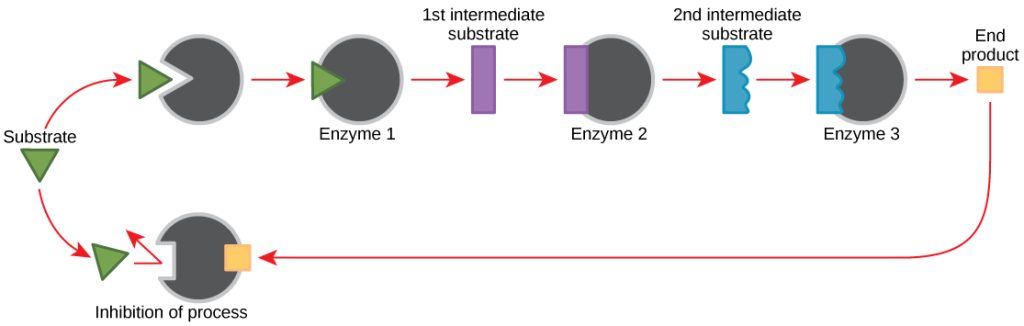

Feedback Inhibition in Metabolic Pathways

Cells have evolved to use the products of their own reactions for feedback inhibition of enzyme activity. Feedback inhibition involves the use of a reaction product to regulate its own further production (Figure 6.1.7). The cell responds to an abundance of the products by slowing down production during anabolic or catabolic reactions, this prevents the cells from wasting nutrients or energy if it does not need it at the time.

Section Summary

- Cells perform the functions of life through various chemical reactions. A cell’s metabolism refers to the combination of chemical reactions that take place within it. Catabolic reactions break down complex chemicals into simpler ones and are associated with energy release. Anabolic processes build complex molecules out of simpler ones and require energy.

- In studying energy, the term system refers to the matter and environment involved in energy transfers. Entropy is a measure of the disorder of a system. The physical laws that describe the transfer of energy are the laws of thermodynamics. The first law states that the total amount of energy in the universe is constant. The second law of thermodynamics states that every energy transfer involves some loss of energy in an unusable form, such as heat energy. Energy comes in different forms: kinetic, potential, and free. The change in free energy of a reaction can be negative (releases energy, exergonic) or positive (consumes energy, endergonic). All reactions require an initial input of energy to proceed, called the activation energy.

- Enzymes are chemical catalysts that speed up chemical reactions by lowering their activation energy. Enzymes have an active site with a unique chemical environment that fits particular chemical reactants for that enzyme, called substrates. Enzymes and substrates are thought to bind according to the “lock and key” or induced-fit model. Enzyme action is regulated to conserve resources and respond optimally to the environment.

Glossary

activation energy: the amount of initial energy necessary for reactions to occur

active site: a specific region on the enzyme where the substrate binds

allosteric inhibition: the mechanism for inhibiting enzyme action in which a regulatory molecule binds to a second site (not the active site) and initiates a conformation change in the active site, preventing binding with the substrate

anabolic: describes the pathway that requires a net energy input to synthesize complex molecules from simpler ones

bioenergetics: the concept of energy flow through living systems

catabolic: describes the pathway in which complex molecules are broken down into simpler ones, yielding energy as an additional product of the reaction

competitive inhibition: a general mechanism of enzyme activity regulation in which a molecule other than the enzyme’s substrate is able to bind the active site and prevent the substrate itself from binding, thus inhibiting the overall rate of reaction for the enzyme

endergonic: describes a chemical reaction that results in products that store more chemical potential energy than the reactants

enzyme: a molecule that catalyzes a biochemical reaction

exergonic: describes a chemical reaction that results in products with less chemical potential energy than the reactants, plus the release of free energy

feedback inhibition: a mechanism of enzyme activity regulation in which the product of a reaction or the final product of a series of sequential reactions inhibits an enzyme for an earlier step in the reaction series

heat energy: the energy transferred from one system to another that is not work

kinetic energy: the type of energy associated with objects in motion

metabolism: all the chemical reactions that take place inside cells, including those that use energy and those that release energy

noncompetitive inhibition: a general mechanism of enzyme activity regulation in which a regulatory molecule binds to a site other than the active site and prevents the active site from binding the substrate; thus, the inhibitor molecule does not compete with the substrate for the active site; allosteric inhibition is a form of noncompetitive inhibition

potential energy: the type of energy that refers to the potential to do work

substrate: a molecule on which the enzyme acts

thermodynamics: the science of the relationships between heat, energy, and work