5.2 The Cell Cycle

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the three stages of interphase

- Discuss the behaviour of chromosomes during mitosis and how the cytoplasmic content divides during cytokinesis

- Define the quiescent G0 phase

- Explain how the three internal control checkpoints occur at the end of G1, at the G2–M transition, and during metaphase

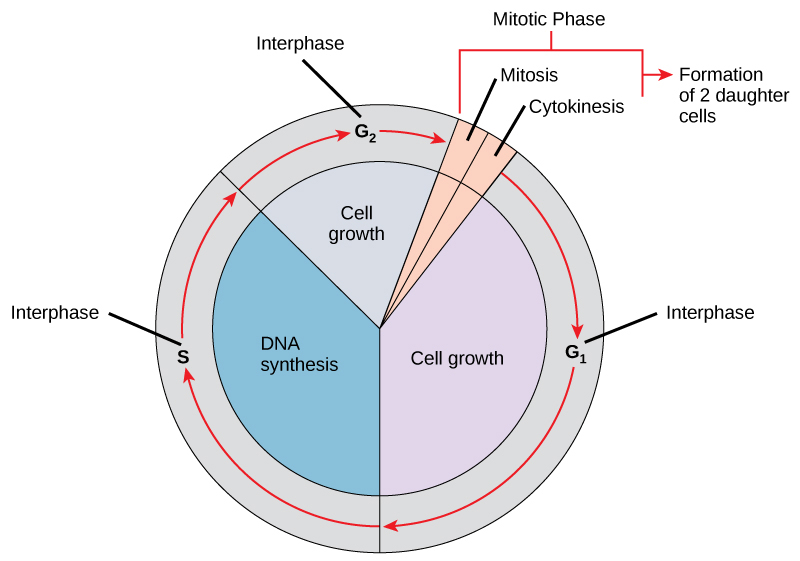

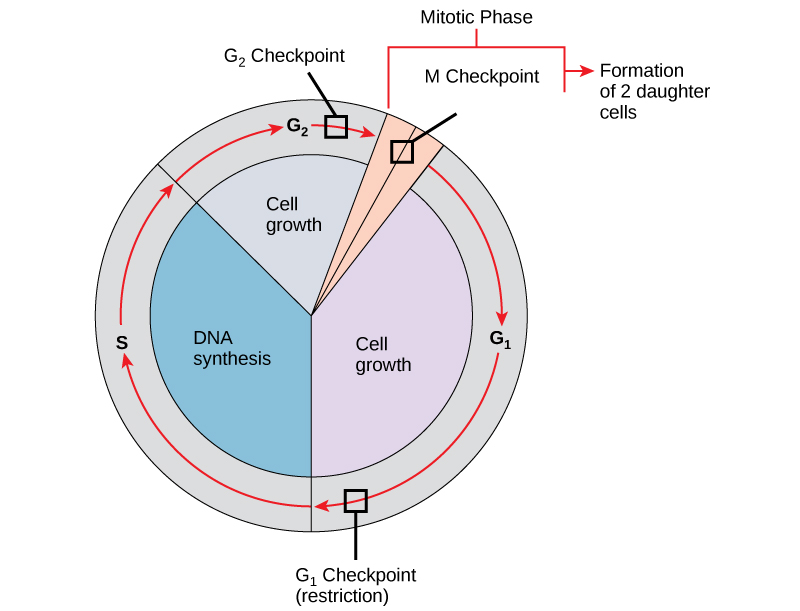

The cell cycle is an ordered series of events involving cell growth and cell division that produces two new daughter cells. Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of precisely timed and carefully regulated stages of growth, DNA replication, and division that produce two genetically identical cells. The cell cycle has two major phases: the interphase and the mitotic phase (Figure 5.2.1). During interphase, the cell grows, and DNA is replicated. During the mitotic phase, the replicated DNA and cytoplasmic contents are separated, and the cell divides.

Watch this video about the cell cycle: The Cell Cycle

Interphase

During interphase, the cell undergoes normal processes while also preparing for cell division. Many internal and external conditions must be met for a cell to move from interphase to the mitotic phase. The three stages of interphase are G1, S, and G2.

G1 Phase

The first stage of interphase is called the G1 phase or first gap because little change is visible. However, during the G1 stage, the cell is quite active at the biochemical level. The cell is accumulating the building blocks of chromosomal DNA and the associated proteins, as well as accumulating enough energy reserves to complete the task of replicating each chromosome in the nucleus.

S Phase

Throughout interphase, nuclear DNA remains in a semi-condensed chromatin configuration. In the S phase (synthesis phase), DNA replication results in the formation of two identical copies of each chromosome—sister chromatids—that are firmly attached at the centromere region. At this stage, each chromosome is made of two sister chromatids and is a duplicated chromosome. The centrosome is duplicated during the S phase. The two centrosomes will give rise to the mitotic spindle, the apparatus that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis. The centrosome consists of a pair of rod-like centrioles at right angles to each other. Centrioles help organise cell division. Centrioles are not present in the centrosomes of many eukaryotic species, such as plants and most fungi.

G2 Phase

In the G2 phase or second gap, the cell replenishes its energy stores and synthesizes the proteins necessary for chromosome manipulation. Some cell organelles are duplicated, and the cytoskeleton is dismantled to provide resources for the mitotic spindle. There may be additional cell growth during G2. The final preparations for the mitotic phase must be completed before the cell is able to enter the first stage of mitosis.

The Mitotic Phase

To make two daughter cells, the contents of the nucleus and the cytoplasm must be divided. The mitotic phase is a multistep process during which the duplicated chromosomes are aligned, separated, and moved to opposite poles of the cell, and then the cell is divided into two new identical daughter cells. The first portion of the mitotic phase, mitosis, is composed of five stages, which accomplish nuclear division. The second portion of the mitotic phase, called cytokinesis, is the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells.

Mitosis

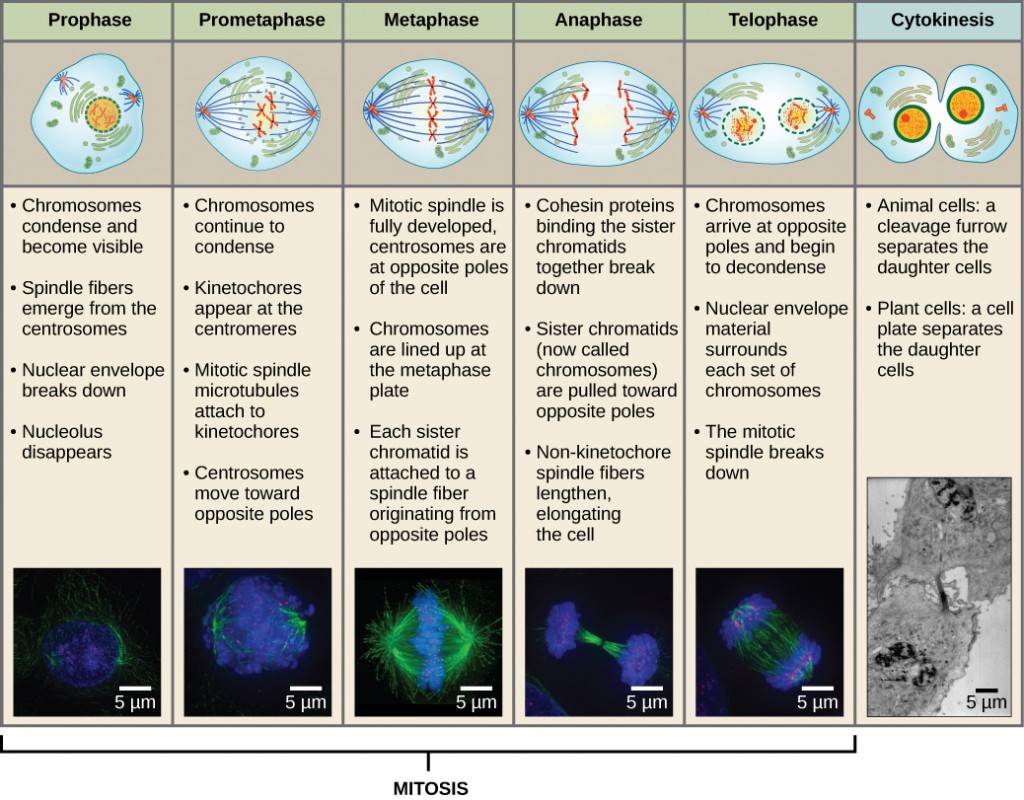

Mitosis is divided into a series of phases—prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—that result in the division of the cell nucleus (Figure 5.2.2).

Visual Connection

Practice Questions

Prophase

During prophase, the “first phase,” several events must occur to provide access to the chromosomes in the nucleus. The nuclear envelope starts to break into small vesicles, and the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum fragment and disperse to the periphery of the cell. The nucleolus disappears. The centrosomes begin to move to opposite poles of the cell. The microtubules that form the basis of the mitotic spindle extend between the centrosomes, pushing them farther apart as the microtubule fibres lengthen. The sister chromatids begin to coil more tightly and become visible under a light microscope.

Prometaphase

During prometaphase, many processes that were begun in prophase continue to advance and culminate in the formation of a connection between the chromosomes and cytoskeleton. The remnants of the nuclear envelope disappear. The mitotic spindle continues to develop as more microtubules assemble and stretch across the length of the former nuclear area. Chromosomes become more condensed and visually discrete. Each sister chromatid attaches to spindle microtubules at the centromere via a protein complex called the kinetochore.

Metaphase

During metaphase, all of the chromosomes are aligned in a plane called the metaphase plate, or the equatorial plane, midway between the two poles of the cell. The sister chromatids are still tightly attached to each other. At this time, the chromosomes are maximally condensed.

Anaphase

During anaphase, the sister chromatids at the equatorial plane are split apart at the centromere. Each chromatid now called a chromosome, is pulled rapidly toward the centrosome to which its microtubule is attached. The cell becomes visibly elongated as the non-kinetochore microtubules slide against each other at the metaphase plate, where they overlap.

Telophase

During telophase, all of the events that set up the duplicated chromosomes for mitosis during the first three phases are reversed. The chromosomes reach the opposite poles and begin to decondense (unravel). The mitotic spindles are broken down into monomers that will be used to assemble cytoskeleton components for each daughter cell. Nuclear envelopes form around chromosomes.

Cytokinesis

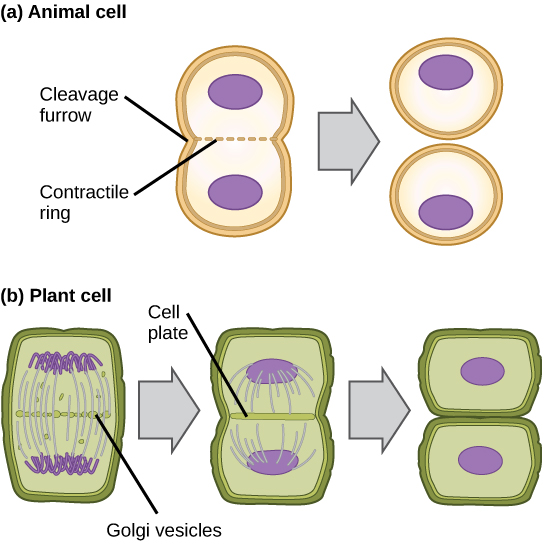

Cytokinesis is the second part of the mitotic phase, during which cell division is completed by the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells. Although the stages of mitosis are similar for most eukaryotes, the process of cytokinesis is quite different for eukaryotes with cell walls, such as plant cells.

In cells such as animal cells that lack cell walls, cytokinesis begins following the onset of anaphase. A contractile ring composed of actin filaments forms just inside the plasma membrane at the former metaphase plate. The actin filaments pull the equator of the cell inward, forming a fissure. This fissure, or “crack,” is called the cleavage furrow. The furrow deepens as the actin ring contracts, and eventually, the membrane and cell are cleaved in two (Figure 5.2.3).

In plant cells, a cleavage furrow is not possible because of the rigid cell walls surrounding the plasma membrane. A new cell wall must form between the daughter cells. During interphase, the Golgi apparatus accumulates enzymes, structural proteins, and glucose molecules prior to breaking up into vesicles and dispersing throughout the dividing cell. During telophase, these Golgi vesicles move on microtubules to collect at the metaphase plate. There, the vesicles fuse from the centre toward the cell walls; this structure is called a cell plate. As more vesicles fuse, the cell plate enlarges until it merges with the cell wall at the periphery of the cell. Enzymes use the glucose that has accumulated between the membrane layers to build a new cell wall of cellulose. The Golgi membranes become the plasma membrane on either side of the new cell wall (Figure 5.2.3).

G0 Phase

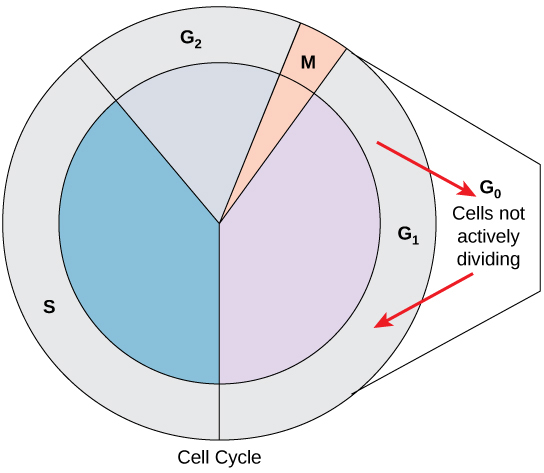

Not all cells adhere to the classic cell-cycle pattern in which a newly formed daughter cell immediately enters interphase, closely followed by the mitotic phase. Cells in the G0 phase are not actively preparing to divide. The cell is in a quiescent (inactive) stage, having exited the cell cycle. Some cells enter G0 temporarily until an external signal triggers the onset of G1. Other cells that never or rarely divide, such as mature cardiac muscle and nerve cells, remain in G0 permanently (Figure 5.2.4).

Control of the Cell Cycle

The length of the cell cycle is highly variable, even within the cells of an individual organism. In humans, the frequency of cell turnover ranges from a few hours in early embryonic development to an average of two to five days for epithelial cells or to an entire human lifetime spent in G0 by specialized cells such as cortical neurons or cardiac muscle cells. There is also variation in the time that a cell spends in each phase of the cell cycle. When fast-dividing mammalian cells are grown in culture (outside the body under optimal growing conditions), the cycle length is approximately 24 hours. In rapidly dividing human cells with a 24-hour cell cycle, the G1 phase lasts approximately 11 hours. The timing of events in the cell cycle is controlled by mechanisms that are both internal and external to the cell.

Regulation at Internal Checkpoints

Daughter cells must be exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes lead to mutations that may be passed to every new cell produced from the abnormal cell. To prevent a compromised cell from continuing to divide, there are internal control mechanisms that operate at three main cell cycle checkpoints at which the cell cycle can be stopped until conditions are favourable. These checkpoints occur near the end of G1, at the G2–M transition, and during metaphase (Figure 5.2.5).

The G1 Checkpoint

The G1 checkpoint determines whether all conditions are favourable for cell division to proceed. The G1 checkpoint also called the restriction point, is the point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell-division process. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check for damage to the genomic DNA at the G1 checkpoint. A cell that does not meet all the requirements will not be released into the S phase.

The G2 Checkpoint

The G2 checkpoint bars the entry to the mitotic phase if certain conditions are not met. As in the G1 checkpoint, cell size and protein reserves are assessed. However, the most important role of the G2 checkpoint is to ensure that all of the chromosomes have been replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged.

The M Checkpoint

The M checkpoint occurs near the end of the metaphase stage of mitosis. The M checkpoint is also known as the spindle checkpoint because it determines if all the sister chromatids are correctly attached to the spindle microtubules. Because the separation of the sister chromatids during anaphase is an irreversible step, the cycle will not proceed until the kinetochores of each pair of sister chromatids are firmly anchored to spindle fibres arising from opposite poles of the cell.

Concept in Action

Watch what occurs at the G1, G2, and M checkpoints by visiting hhmi Biointeractives. animation.

Practice Questions

Section Summary

- The cell cycle is an orderly sequence of events.

- Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of precisely timed and carefully regulated stages.

- In eukaryotes, the cell cycle consists of a long preparatory period called interphase. Interphase is divided into G1, S, and G2 phases.

- Mitosis consists of five stages: prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Mitosis is usually accompanied by cytokinesis, during which the cytoplasmic components of the daughter cells are separated either by an actin ring (animal cells) or by cell plate formation (plant cells).

- Each step of the cell cycle is monitored by internal controls called checkpoints. There are three major checkpoints in the cell cycle: one near the end of G1, a second at the G2–M transition, and the third during metaphase.

the ordered sequence of events that a cell passes through between one cell division and the next

the period of the cell cycle leading up to mitosis; includes G1, S, and G2 phases; the interim between two consecutive cell divisions

the period of the cell cycle when duplicated chromosomes are distributed into two nuclei and the cytoplasmic contents are divided; includes mitosis and cytokinesis

(also, first gap) a cell-cycle phase; first phase of interphase centered on cell growth during mitosis

the second, or synthesis phase, of interphase during which DNA replication occurs

the microtubule apparatus that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis

the period of the cell cycle at which the duplicated chromosomes are separated into identical nuclei; includes prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase

a paired rod-like structure constructed of microtubules at the center of each animal cell centrosome

(also, second gap) a cell-cycle phase; third phase of interphase where the cell undergoes the final preparations for mitosis

the stage of mitosis during which chromosomes condense and the mitotic spindle begins to form

the stage of mitosis during which mitotic spindle fibers attach to kinetochores

a protein structure in the centromere of each sister chromatid that attracts and binds spindle microtubules during prometaphase

the stage of mitosis during which chromosomes are lined up at the metaphase plate

the equatorial plane midway between two poles of a cell where the chromosomes align during metaphase

the stage of mitosis during which sister chromatids are separated from each other

the stage of mitosis during which chromosomes arrive at opposite poles, decondense, and are surrounded by new nuclear envelopes

the division of the cytoplasm following mitosis to form two daughter cells

a constriction formed by the actin ring during animal-cell cytokinesis that leads to cytoplasmic division

a structure formed during plant-cell cytokinesis by Golgi vesicles fusing at the metaphase plate; will ultimately lead to formation of a cell wall to separate the two daughter cells

a cell-cycle phase distinct from the G1 phase of interphase; a cell in G0 is not preparing to divide

describes a cell that is performing normal cell functions and has not initiated preparations for cell division

mechanisms that monitor the preparedness of a eukaryotic cell to advance through the various cell cycle stages