3.1 What is Organic Chemistry?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the significance of organic chemistry in health sciences

- Explain the unique properties of carbon that make it essential for life

- Differentiate between organic and inorganic compounds

Organic Chemistry for Health Sciences

Organic Chemistry is the branch of chemistry that delves into the study of carbon-containing compounds. While the term “organic” may evoke thoughts of farmers’ markets and pesticide-free produce, it is, in fact, a testament to the richness and diversity of carbon chemistry. Organic compounds are the building blocks of life and understanding them is crucial for comprehending the molecules that compose our cells, tissues, and the pharmaceuticals that aid us in our pursuit of better health.

In this chapter, we will explore the structure and properties of organic compounds and delve into the nomenclature and classification systems that allow us to systematically identify and name these compounds. We will also discuss the important concepts of isomerism and stereochemistry, which are essential for grasping the three-dimensional nature of organic molecules.

Furthermore, this chapter will introduce you to some of the key organic reactions and mechanisms, including the fundamental processes of acid-base chemistry, addition reactions, and other reactions involving functional groups found in biological molecules. These principles serve as the basis for understanding the interactions of drugs, enzymes and metabolic pathways within the human body.

By the end of this chapter, you will have gained a solid foundation in the principles and language of organic chemistry, equipping you with the knowledge necessary for success in the field of health sciences and a deeper appreciation of the intricacies of life itself.

Why Carbon?

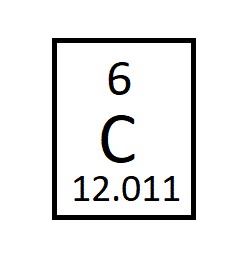

Carbon, atomic number 6, is an element with atoms that are small and relatively simple. The nucleus contains 6 positively charged protons, and there are 6 electrons outside the nucleus distributed into two shells. The outer shell has four electrons that are held quite strongly by the electrostatic pull from the nucleus. So, while a carbon atom can be ionized through either the gain or loss of electrons, it does not tend to do so. Carbon does, however, readily engage in covalent bonding, sharing electrons with neighboring atoms and forming tight associations with them. The four valence electrons in a carbon atom can do this by forming four single bonds, or by forming two single bonds and a double bond, by forming one single bond and a triple bond, or by forming two double bonds.

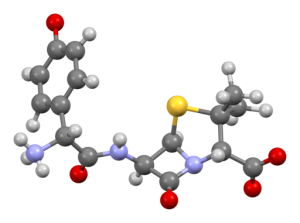

Carbons covalently bond with one another, also, forming chains of various lengths, and rings. Carbon readily bonds with other atoms such as oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen, forming quite stable arrangements with these common elements as well.

The architecture of carbon structures is therefore fantastically varied. Small organic molecules might contain just one or two carbon atoms surrounded by other atoms. But the larger organic molecules can contain hundreds or thousands of carbons, linked with rings and bridges and other complex structures that fold into particular three-dimensional structures.

Carbon is a bit like a basic Lego building block. The 6-pin Lego is able to make lots of other connections, and also can make strong, stable connections. It has the features that make it an ideal basic building block for the construction of a wide variety of larger, complex shapes necessary for biological functions. In a similar fashion, carbon can make 4 bonds with varying geometry and generally stable structures.

No other element can quite do what carbon does: silicon has the ability to form four bonds with other atoms, but those bonds tend to be weak due to the additional electron shell in a silicon atom. Nitrogen has five valence electrons so generally only forms 3 single bonds, limiting its usefulness. Boron, similarly, does not make for a dependable, stable base structure.

Organic Chemistry versus Inorganic Chemistry

In the game “20 Questions,” one player thinks of something, and another is tasked with discovering what that thing is through a process of questioning. Up to 20 questions can be asked in an attempt to hone in on the answer. Frequently, a questioner will ask “Animal, vegetable, or mineral?” early in the questioning, to narrow all the possible options down quickly. Nearly everything in the universe can be classified into one of these categories.

Students of chemistry often are introduced quite early to a set of similarly broad categories: pure substances are classified as ionic, molecular (covalent) or metallic. Interestingly, these categories have some significant overlap with the categories from the 20 Questions: animals and vegetables are mostly composed of the elements carbon, hydrogen and oxygen and have other features characteristic of molecular substances. The materials they are made of can be burned in oxygen to yield carbon dioxide and water, and they may be present in any of three common physical states (solid, liquid, gas) under normal room conditions. They are mostly covalent in nature. In contrast, minerals typically contain metal as well as non-metal elements and have features characteristic of ionic substances. They do not combust; they are usually solids under normal conditions and sometimes have recognizable crystalline structures. In certain conditions high heat can cause them to react to release pure metals – shiny, ductile and conductive materials that harden as they cool to form shiny solids.

Table 3.1.1: General Contrasting Properties and Examples of Organic and Inorganic Compounds

| Organic | Hexane | Inorganic | NaCl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| low melting points | −95°C | high melting points | 801°C | |

| low boiling points | 69°C | high boiling points | 1,413°C | |

| low solubility in water; high solubility in nonpolar solvents | insoluble in water; soluble in gasoline | greater solubility in water; low solubility in nonpolar solvents | soluble in water; insoluble in gasoline | |

| flammable | highly flammable | nonflammable | nonflammable | |

| aqueous solutions do not conduct electricity | nonconductive | aqueous solutions conduct electricity | conductive in aqueous solution | |

| exhibit covalent bonding | covalent bonds | exhibit ionic bonding | ionic bonds |

Given these general links, it may seem reasonable to think there might be some fundamental distinction between chemical substances that come from living things (animals and vegetables) and those that come from the rocky earth (mineral). Is the chemistry of living things fundamentally different to that of non-living things?

Not so long ago, people believed there was such a fundamental difference. This view called “vitalism”, that living and nonliving material was fundamentally different, was generally accepted within and outside of scientific circles through much of the 1700s.

Experimental evidence began to reveal inconsistencies between this view and reality, however. In 1828 a German chemist named Friederich Wohler provided what may have been the final blow to the idea: he took material from the non-living world and used it to produce urea, a known biochemical. The urea he produced was exactly the same as the biologically sourced urea: they were indistinguishable.

Wohler’s discovery wasn’t planned. When he reacted silver cyanate and ammonium chloride he expected to get ammonium cyanate, as described by this equation:

AgOCN + NH4Cl → AgCl + NH4OCN

But what he got was urea: NH2CONH2. Once he knew this, the significance became clear.

And so, the idea of vitalism faded, and chemistry continued to reveal in all kinds of ways that the universal basic building blocks of all matter were the same atoms, from the same elements, bonded together the same way no matter where a substance came from.

Organic Compounds in Living Systems

The elemental makeup of the living and nonliving materials was found to be different in one way, however. The distribution of elements varied between them, with a wide variety of material from living sources full of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. These “organic” materials were categorized in that way due to their relationship with life and nature. They gradually became defined by chemists in a more modern fashion: organic chemistry is the chemistry of carbon compounds.

Nature is filled with chemical structures of many types, but in the chemistry of life we find an abundance of organic chemicals. Carbon has an outsized role to play in life, and thus in our chemical activities. Agriculture, manufactured goods from agricultural products (e.g. textiles), and pharmaceutical products all are largely based on organic molecules. The petroleum industry, and all the products related to that, are also linked to organic chemistry because petroleum is a fossil fuel, produced in geologic processes from formerly living matter. In modern times these substances are the raw materials converted into a huge variety of plastics that we use in constructing the built world.

Chemists have found ways to alter and adjust organic structures in order to build all sorts of novel and interesting structures, through a process called “synthesis”. The flexibility of organic chemistry far surpasses that of most other elements, so organic chemistry has grown to a huge sub-field of chemistry, and entire classes (such as this one) are taught on the subject.

Practice Questions

Study Case – The Properties of Sucrose: Organic or Inorganic?

Exercise 3.1.1 – Drag and drop organic substances

An Inspiring TED Talk on Organic Chemistry

Section Summary

- Organic chemistry studies carbon-containing compounds, crucial for understanding life processes and pharmaceutical interactions, focusing on structure, properties, and reactions of organic molecules.

- Carbon’s ability to form stable covalent bonds and create diverse molecular structures makes it essential for biological functions, similar to a versatile building block like Lego.

- Organic compounds (like hydrocarbons) typically have low melting/boiling points, covalent bonding, and are flammable, while inorganic compounds (like salts) have higher melting points, ionic bonding, and are nonflammable.

- Organic chemistry plays a central role in life and industry, from agriculture to pharmaceuticals, plastics, and petroleum. Organic synthesis allows the creation of novel materials and molecules.