3.3.1 Hydrocarbons: Names and Structures

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Apply IUPAC naming rules to hydrocarbons

- Differentiate between structural and geometric isomers

- Interpret the significance of nomenclature in chemical communication

The IUPAC Nomenclature

The IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) nomenclature, often used in the systematic naming of organic compounds, follows a consistent set of rules:

- Number of Carbon Atoms: The prefix indicates the number of carbon atoms in the main carbon chain. For example, “meth-” represents one carbon, “eth-” represents two carbons, “prop-” represents three carbons, and so on.

- Type of Bond: When the carbon atoms in the main chain are connected by single bonds, “ane” is added to the end of the prefix. For example, “methane” has one carbon with single bonds, “ethane” has two carbons with single bonds, and so forth.

- Double Bonds: If there is at least one double bond in the main carbon chain, the suffix “ene” is used. For instance, “ethene” signifies two carbons connected by a double bond, while “butene” indicates four carbons with at least one double bond.

- Triple Bonds: When there is at least one triple bond in the main carbon chain, the suffix “yne” is added. “Ethyne” refers to two carbons connected by a triple bond, and “pentynes” would have at least one triple bond with five carbons in the main chain.

- Branching: If the main carbon chain has side branches, they are indicated by prefixes such as “methyl-” (one carbon branch), “ethyl-” (two carbon branches), and so on.

These rules allow scientists to systematically name hydrocarbon compounds, providing a precise description of their structure and composition. This nomenclature system ensures that a compound’s name accurately reflects its molecular structure, making it a crucial tool in organic chemistry.

Prefixes for Naming the Number of Carbon Atoms

The prefixes – “start” of the chemical name – are integral to the systematic naming of hydrocarbon compounds, allowing scientits to precisely convey the number of carbon atoms in the main chain, which is a fundamental characteristic of organic molecules.

- Meth-: This prefix denotes one carbon atom in the main chain. For example, “methane” has one carbon atom.

- Eth-: “Eth-” represents two carbon atoms in the main chain. “Ethane” is a hydrocarbon with two carbon atoms.

- Prop-: When you see “prop-,” it signifies three carbon atoms in the primary carbon chain. “Propane” is an example with three carbons.

- But-: “But-” denotes four carbon atoms in the main chain. “Butane” contains four carbon atoms in its structure.

- Pent-: The prefix “pent-” indicates five carbon atoms in the main chain. “Pentane” has a chain of five carbons.

- Hex-: “Hex-” signifies six carbon atoms in the primary chain. “Hexane” contains six carbon atoms.

- Hept-: When you come across “hept-” it represents seven carbon atoms in the main chain. “Heptane” is an example with seven carbons.

- Oct-: “Oct-” denotes eight carbon atoms in the main chain. “Octane” has eight carbons in its structure.

- Non-: This prefix is used to indicate nine carbon atoms in the main chain. “Nonane” has nine carbons.

- Dec-: “Dec-” signifies ten carbon atoms in the primary carbon chain. “Decane” is a hydrocarbon with ten carbon atoms.

Naming Alkanes, Alkenes and Alkynes

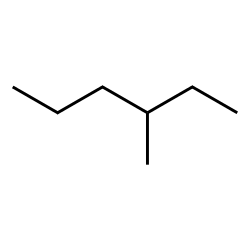

You have already learned the basic naming conventions for small (1-10 carbon) straight chain and somewhat branched alkanes. These include a suffix ‘ane’ to indicate membership in the alkane family, the base of the name related to the number of carbons (e.g. ‘hex’ for a six-carbon parent chain) and indication of branching with a location for the branch and a name for it:

Check your understanding by completing the questions in the short quiz here.

Practice Questions

Exercise 3.3.1-1

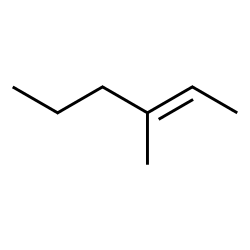

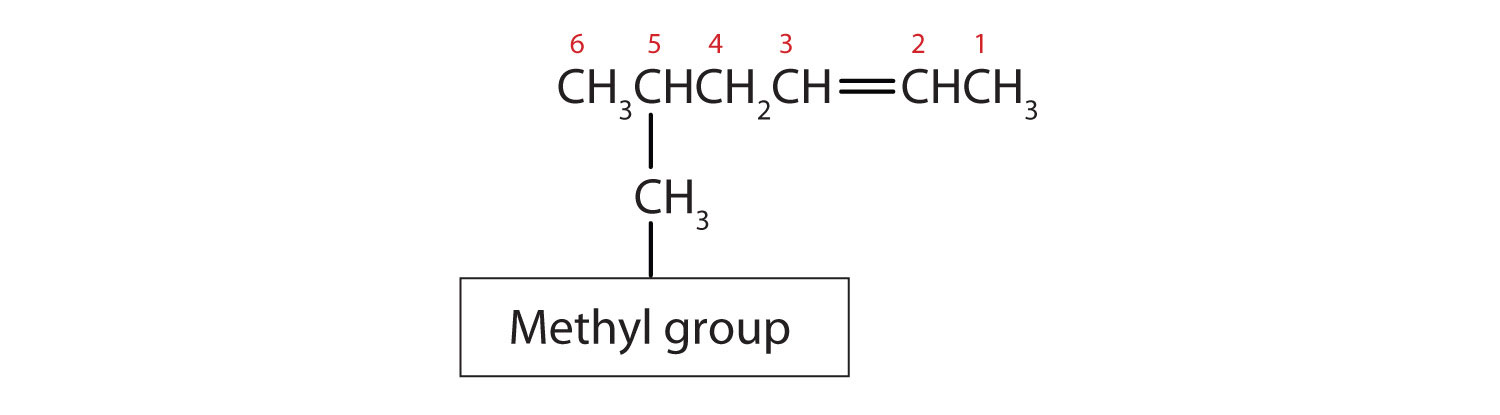

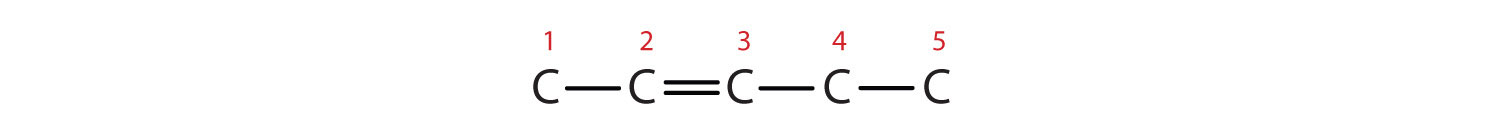

When faced with a structure containing a functional group such as an alkene, the name of the related alkane can be a good starting point. Most elements of the name will be the same, with the exception that the identity and location of the functional group itself needs to be conveyed somehow. For the alkenes, the suffix used is no longer ‘ane,’ but is now ‘ene.’ The location of the double bond is identified with a number. Count a parent chain that includes the alkene, counting from the end of the chain with the lowest possible number assignment given to the double bond. Then use the number of the carbon where the double bond is first encountered as the location indicator. Current IUPAC rules put the number immediately before the ‘ene’ suffix, but name changes are sometimes accepted rather slowly; it remains very common to see this number earlier in the name:

Acceptable names for this molecule include 3-methylhex-2-ene and 3-methyl-2-hexene. IUPAC rules encourage placing the location identifier close to the feature at that location. The first name follows IUPAC rules to the letter. However, these names can seem awkward even to chemists, and the second form is used frequently.

Other aspects of naming alkenes are identical to the process used for alkanes: the parent chain is indicated by the base name and the branches are numbered and named just as they are for alkanes.

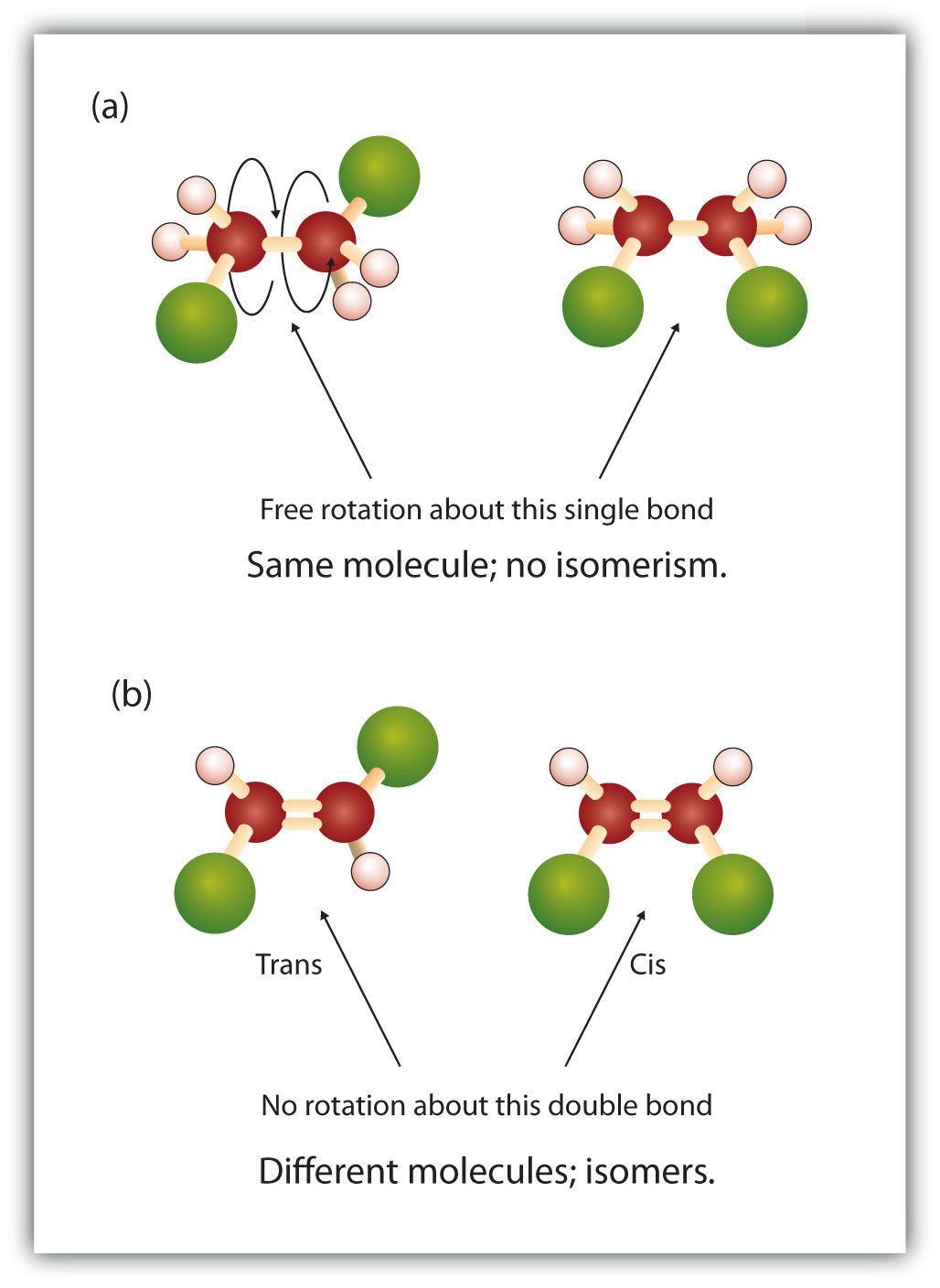

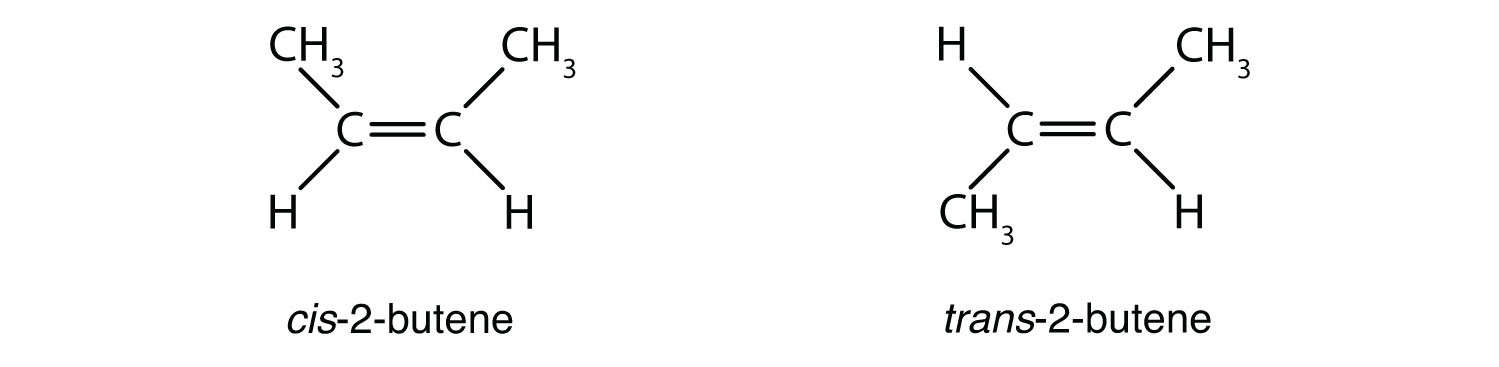

Geometric Isomers in Alkenes

One other structural variation occurs with alkenes. The geometry of the carbon-carbon double bond is fixed, with no rotation along the axis of the double bond. Thus, two different isomers of a substance are often possible. Just like the structural isomers we have already considered; these are related but different compounds that have the same molecular formula. However, the geometric isomers are also the same in terms of their atom connectivity: each atom in the molecule has the same types of bonds (same connections) to its neighbors. The difference lies only in the 3-dimensional layout of the molecule.

The word prefixes ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ are commonly used to indicate which of the two geometric isomers is being identified.

The ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ nomenclature is based on the parent chain: if the chain comes into the double bond on one side (long axis) of the double bond and leaves on the same side, it is a ‘cis’ isomer. If the parent chain leaves the double bond opposite where it came in, the isomer is termed ‘trans.’

IUPAC has a system for handling the distinction between these geometric isomers that uses the letters E and Z. For IUPAC, E and Z names are derived by applying a set of rules that rank the groups connected to each carbon of the double bond and assign one with a higher priority than the other. By then following the trail of these groups, from higher priority atom through the two carbons of the double bond and out the other side, the arrangement can be identified and named. If these higher priority groups enter and exit the alkene on the same side (along the axis of the double bond) the molecule is described as ‘Z,’ short for zusammen, German for ‘together.’ If the groups enter and exit the double bond on opposite sides the structure is identified as ‘E’ for entgegen, meaning ‘opposite.’

Z and E isomers often correspond with cis and trans isomers, but not always, since the priority groups are usually but not always in the parent chain.

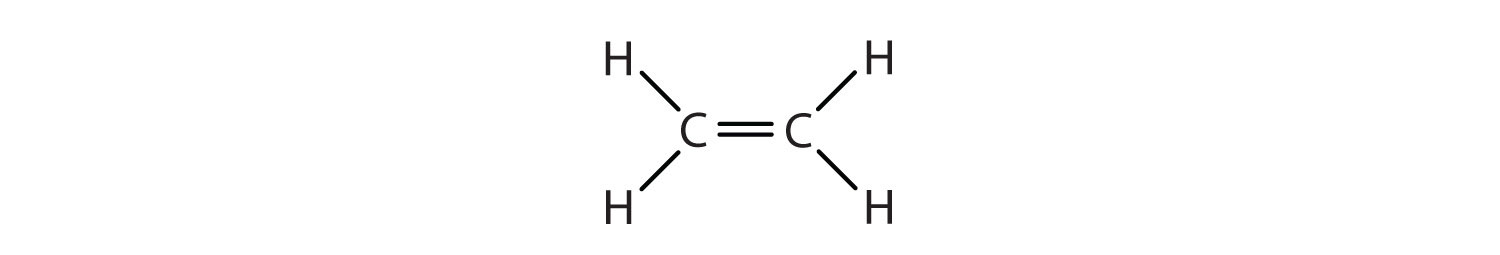

Note that alkenes at the end of a carbon chain will not exhibit this kind of isomerism, because the carbon at the end of the chain has two hydrogens on it:

Why does this geometric distinction matter? The reason is because these isomers are different substances and will have different characteristics. Specific isomers must be incorporated into pharmaceuticals containing alkenes, for instance, if they are to have the desired characteristics and not deleterious effects.

If you reconsider the structure above, you should now recognize that it is one of these isomers. Since the parent chain comes into carbon 2 from below and exits from carbon three above the plane of the double bond, this is a trans isomer and could be better named as E-3-Methylhex-2-ene.

Remember these systematic names are coded information, and like any code it takes time and practice (and frequent errors along the way) to learn. With repeated use the code becomes familiar, and you can become fluent in reading and understanding the names and structures.

You can practice naming some alkenes by completing the quiz here.

Practice Questions

Exercise 3.3.1-2

Alkynes are named similarly to alkenes but without the concern for designating cis or trans isomers.

Exercise 3.3.1-3

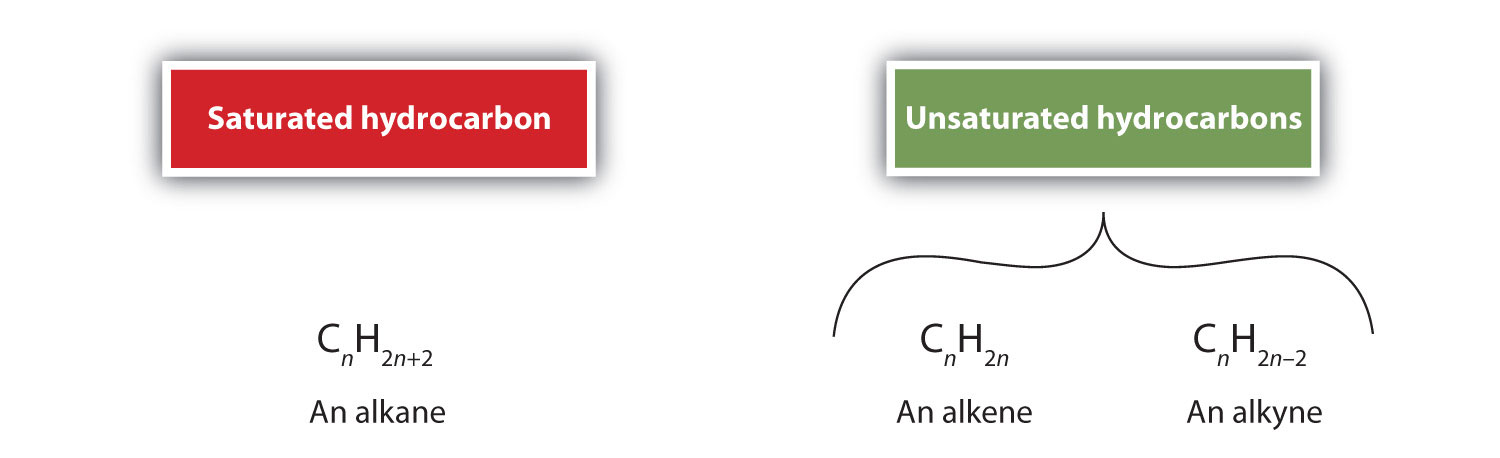

An alkene or alkyne having one or more multiple (double or triple) bonds between carbon atoms is called unsaturated. This is because they have fewer hydrogen atoms than does an alkane with the same number of carbon atoms, as is indicated in the following general formulas:

Summary of Naming Rules for Alkenes and Alkynes

The Rules for Naming Alkenes According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) are summarized here:

- The longest chain of carbon atoms containing the double or triple bond is considered the parent chain. It is named using the same stem as the alkane having the same number of carbon atoms but ends in –ene to identify it as an alkene. Thus, the compound CH2=CHCH3 is propene. Alkynes are similarly indicated, using the suffix -yne.

- If there are four or more carbon atoms in a chain, we must indicate the position of the double or triple bond. The carbons atoms are numbered so that the first of the two that are doubly or triply bonded is given the lower of the two possible numbers. The compound CH3CH=CHCH2CH3, for example, has the double bond between the second and third carbon atoms. Its name is 2-pentene (not 3-pentene).

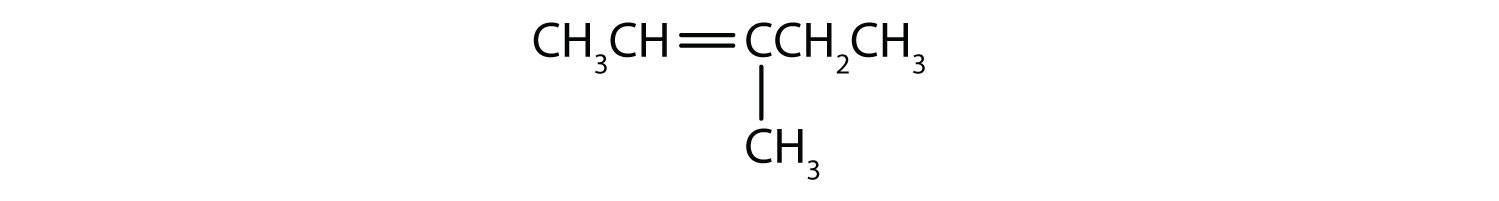

-

Substituent groups are named as with alkanes, and their position is indicated by a number. Thus,

is 5-methyl-2-hexene. Note that the numbering of the parent chain is always done in such a way as to give the double bond the lowest number, even if that causes a substituent to have a higher number. The double bond always has priority in numbering.

- For alkenes, identify the specific geometric isomer as necessary by using the E or Z tag.

Worked Examples

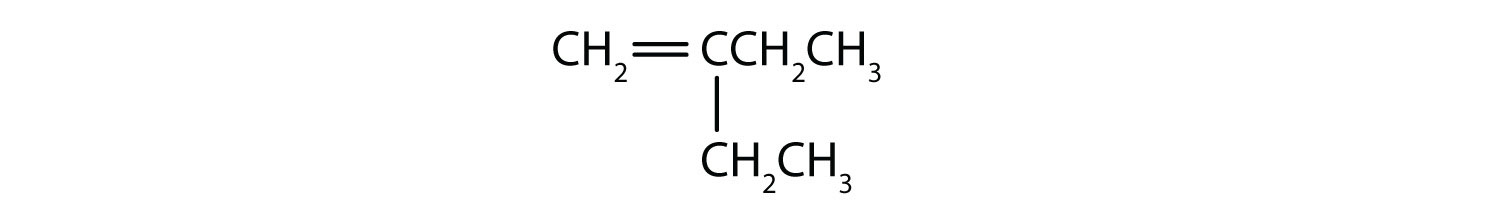

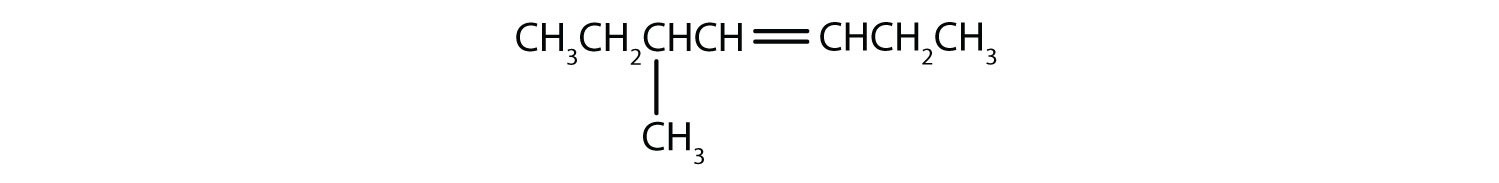

Name each compound, without concerning yourself with E/Z designation.

Solution

- The longest chain containing the double bond has five carbon atoms, so the compound is a pentene (rule 1). To give the first carbon atom of the double bond the lowest number (rule 2), we number from the left, so the compound is a 2-pentene. There is a methyl group on the fourth carbon atom (rule 3), so the compound’s name is 4-methyl-2-pentene.

- The longest chain containing the double bond has four carbon atoms, so the parent compound is a butene (rule 1). (The longest chain overall has five carbon atoms, but it does not contain the double bond, so the parent name is not pentene.) To give the first carbon atom of the double bond the lowest number (rule 2), we number from the left, so the compound is a 1-butene. There is an ethyl group on the second carbon atom (rule 3), so the compound’s name is 2-ethyl-1-butene.

Exercise 3.3.1-4

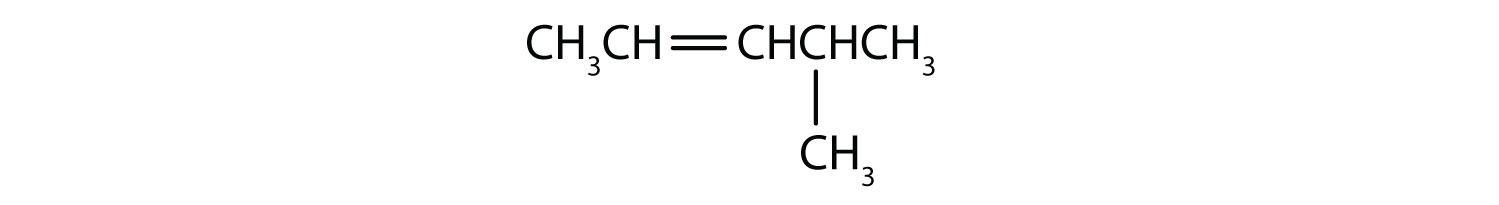

Name this compound, without specifying which geometric isomer:

CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2CH=CHCH3

Exercise 3.3.1-5

Name this compound without specifying which geometric isomer:

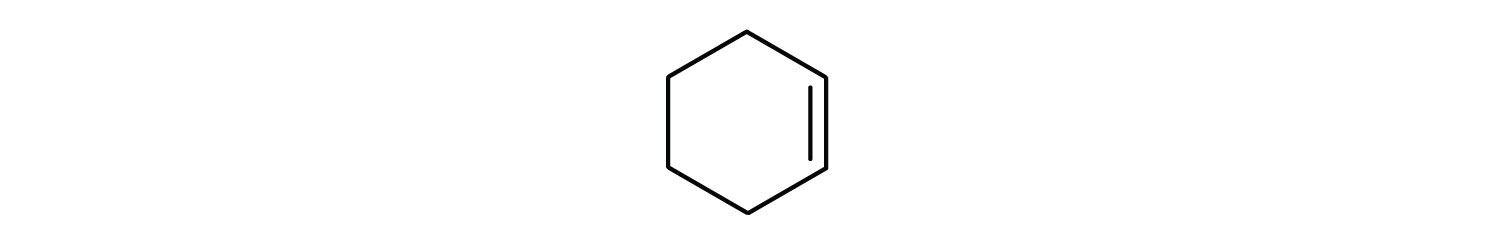

Just as there are cycloalkanes, there are cycloalkenes. These compounds are named like alkenes, but with the prefix cyclo– attached to the beginning of the parent alkene name.

Worked Examples

Draw the structure for each compound.

- 3-methyl-2-pentene

- cyclohexene

Solution

-

First write the parent chain of five carbon atoms: C–C–C–C–C. Then add the double bond between the second and third carbon atoms:

Now place the methyl group on the third carbon atom and add enough hydrogen atoms to give each carbon atom a total of four bonds.

-

First, consider what each of the three parts of the name means. Cyclo means a ring compound, hex means 6 carbon atoms, and –ene means a double bond.

Section Summary

- The IUPAC system assigns systematic names to organic compounds based on the number of carbon atoms in the main chain, type of bonds (single, double, or triple), and any branching present. For example, “meth-” indicates one carbon, and suffixes like “-ane,” “-ene,” and “-yne” denote single, double, and triple bonds, respectively.

- The prefixes such as “meth-,” “eth-,” “prop-,” etc., denote the number of carbon atoms in the parent chain. For example, “meth-” represents one carbon, and “dec-” represents ten carbon atoms.

- Alkenes and alkynes are named similarly to alkanes, but with different suffixes: “-ene” for alkenes and “-yne” for alkynes. The position of the double or triple bond is indicated by numbering the carbon chain from the end that gives the lowest number to the bond.

- Alkenes can have geometric isomers (cis/trans or E/Z) due to the fixed geometry of the carbon-carbon double bond. This affects their physical and chemical properties. “Cis” and “trans” describe the relative positions of groups attached to the double bond, while IUPAC uses “E” and “Z” for priority-based nomenclature.

- Cycloalkenes are named similarly to alkenes but with the prefix “cyclo-” to indicate the compound forms a ring. For example, cyclohexene is a six-carbon ring with a double bond.