3.3.2 Properties of Hydrocarbons and Hydrocarbon Polymers

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the physical and chemical properties of hydrocarbons

- Discuss the role of hydrocarbons in industries

- Define polymerisation reactions

- Explain the polyethylene synthesis

General Properties of Hydrocarbons

Hydrocarbons are non-polar substances, with weak intermolecular forces. Their properties are influenced by the lack of strong intermolecular attractive forces. As a group they have relatively low melting and boiling temperatures, and they are poorly or not at all soluble in polar solvents, including water.

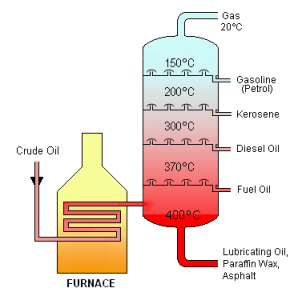

The sources of these substances for industry and commerce tend to be geologic deposits of gases (‘natural gas’) and the liquid oil, ‘crude oil.’ These substances along with the solid bitumen make up ‘petroleum,’ a word which in casual use is often used to describe just liquid material. These raw materials are processed in many ways, typically first by distillation to separate out the hydrocarbon components in them. Hydrocarbons are separated by boiling points in distillation, which corresponds to their molecular weights. Fractions containing mixtures of similarly-boiling substances are collected from the distillations and then can be further refined and/or transformed into products of increasing value.

The lower molecular weight, small hydrocarbons are gases under normal conditions. Many are important substances industrially and in daily life. Methane, for instance, is the principal component of natural gas. It is a gaseous substance with a low boiling point and low reactivity except for its tendency to combust. The slightly larger alkanes ethane, propane and butane are also gases under normal environmental conditions. These also are important industrial feedstocks and are often combusted to release energy.

With increased molecular size, the weak London forces operating between alkane molecules begin to provide enough intermolecular attraction for these substances to exist as liquids. Gasoline, for instance, is a complex mixture but consists mostly of alkanes with 5-8 carbons.

Somewhat larger hydrocarbons, while still liquid, are more viscous and have higher boiling points, and are used as kerosene and motor oil. Mineral oil (‘baby oil’) is also composed of alkanes in this group; petroleum jelly (Vaseline™) is similar.

At higher molecular weights, another fraction of alkanes are waxy solids. Blends of this distilled fraction of crude oil are sold as paraffin.

Note that all of the substances described here are obtained through mining: from the tapping of natural gas (methane) wells to the processing of liquid crude oil. These substances originated as dead material from living organisms that have been held and pressurized under the surface of the earth for geologic time spans. In these processes which occur in oxygen-poor environments, the production of hydrocarbons is favored over more oxidized organic compounds like alcohols.

The hydrocarbons are the raw materials used by enormous industries around the world. This includes the fossil fuel and gasoline industry, the plastics industry and the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries, all of which make heavy use of oil and gas-derived materials. Our quality of life has been heavily impacted by these substances for better and for worse. At the moment these substances are inexpensive and readily available materials that can be chemically altered to suit our needs, and we rely on them. Substituting for these materials is often difficult because there is no source of hydrocarbons as abundant, anywhere on earth. The geologic processes leading to the formation of petroleum occur in an oxygen-deficient environment, producing highly reduced carbons in these substances from decaying material. At the earth’s surface, abundant oxygen leads to the production of compounds with more oxidized carbons.

The nonpolar nature of crude oil chemicals contributes to environmental problems associated with oil spills. Spilled crude oil floats at the surface of water. It streams outward over huge areas and thus impacts large areas near a spill. Non-polar materials are not easily removed by water, since they do not dissolve in polar solvents, complicating cleanup.

Alkenes, alkynes and aromatic compounds exist in the complex mixtures we get from oil and gas, but these functional groups also show up in biological material at the surface of the earth. Alkenes and alkynes are prone to some reactions however, which means that they do not exist in stable forms in the environment to the same degree as alkanes.

Table 3.3.2.1: Physical Properties of Some Selected Alkenes (like alkanes they have low melting and boiling point temperatures).

| IUPAC Name | Molecular Formula | Condensed Structural Formula | Melting Point (°C) | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ethene | C2H4 | CH2=CH2 | –169 | –104 |

| propene | C3H6 | CH2=CHCH3 | –185 | –47 |

| 1-butene | C4H8 | CH2=CHCH2CH3 | –185 | –6 |

| 1-pentene | C5H10 | CH2=CH(CH2)2CH3 | –138 | 30 |

| 1-hexene | C6H12 | CH2=CH(CH2)3CH3 | –140 | 63 |

| 1-heptene | C7H14 | CH2=CH(CH2)4CH3 | –119 | 94 |

| 1-octene | C8H16 | CH2=CH(CH2)5CH3 | –102 | 121 |

Synthetic Polymers

The most important commercial use of alkenes relates to polymerizations, reactions in which small molecules, referred to in general as “monomers”, are converted into enormous ones. These polymers are giant molecules formed by the combination of monomers in a repeating manner. A polymer is as different in characteristics from its monomer as a long strand of spaghetti is from a tiny speck of flour. For example, polyethylene, the familiar waxy material used to make plastic bags, is made from the monomer ethylene—a gas. Polyethylene is produced in astounding quantities: as of 2017, over 100 million tons were produced each year (source: Wikipedia).

The Production of Polyethylene

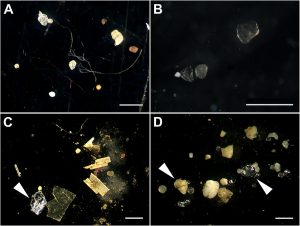

Polyethylene pellets are produced through the polymerization of gaseous ethene to produce the solid product. These pellets, called nurdles, are a commercial product which can be manipulated to form a wide variety of consumer products.

Nurdles of polyethylene can be melted and formed into sheets, bags, bottles, pipes etc. Polyethylene can be mixed with other materials to manipulate the properties of the finished product so that it is harder or more flexible, colored or resistant to ultraviolet light. This versatility has made it immensely popular as a raw material.

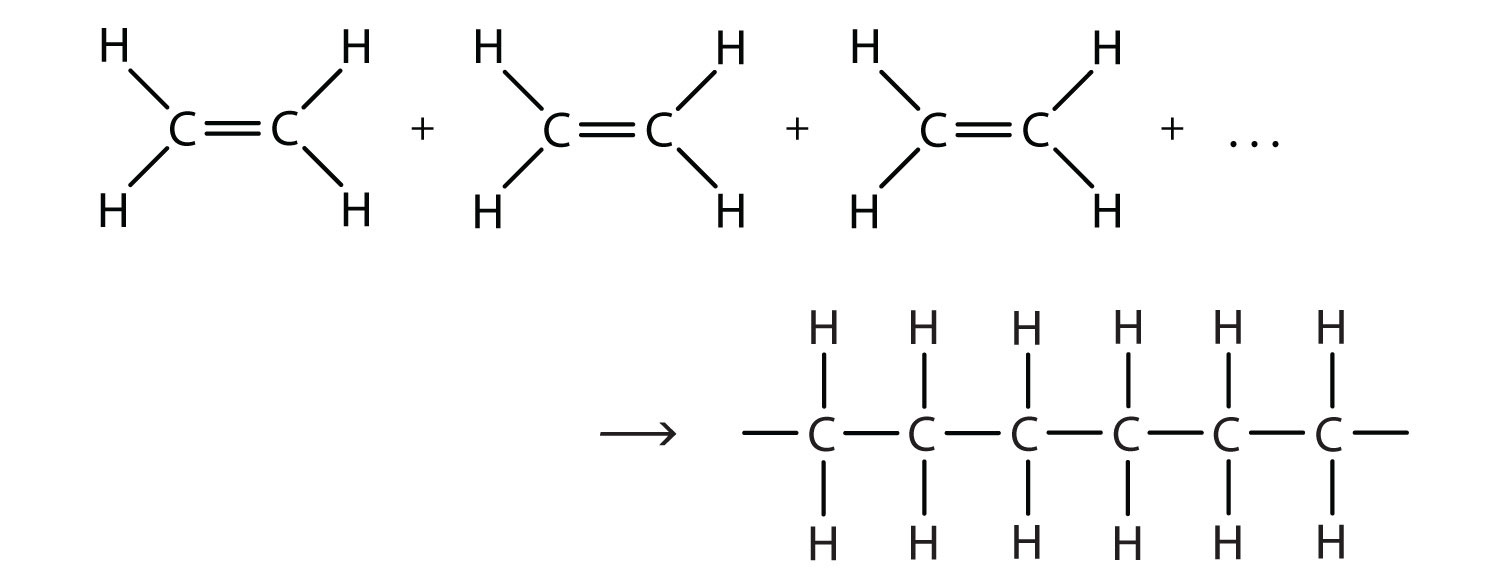

Polyethylene is made by a chemical process called “addition polymerization”, in which monomers add to one another to produce a polymeric product that contains all the atoms of the starting monomers. Ethene molecules are joined together in long chains. The polymerization can be represented by the reaction of a few monomer units:

The bond lines extending at the ends in the formula of the product indicate that the structure extends for many units in each direction. Notice that all the atoms—two carbon atoms and four hydrogen atoms—of each monomer molecule are incorporated into the polymer structure.

Polyethylene is so stable that it exists in the environment for a very long time after disposal. With enormous production and such a long lifespan, plastic pollution (from polyethylene as well as other plastics) is increasingly concerning. The discovery of microplastics, which are minute bits of plastic material in the environment in all kinds of remote environments and in the bodies of animals, has led to increasing worry about the impacts of our plastic use on our health and the health of the environment.

The scale of the problem is immense: more than half the compounds produced by the chemical industry are synthetic polymers. Most of this material resists chemical decomposition through natural processes.

Polyethylene is not the only polymer produced at such a scale. Some other common addition polymers are listed in the table below. Many polymers are mundane (e.g. plastic bags, food wrap, toys and tableware) but there are also polymers that conduct electricity, have amazing adhesive properties, or are stronger than steel but much lighter in weight. Specialized polymers are increasingly developed and selected for very specific purposes, such as medical applications.

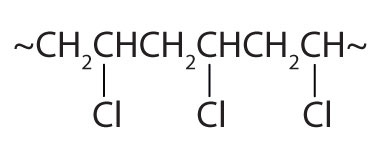

Table 3.3.2.2: Some Additional Polymers

| Monomer | Polymer | Polymer Name | Some Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH2=CH2 | ~CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2~ | polyethylene | plastic bags, bottles, toys, electrical insulation |

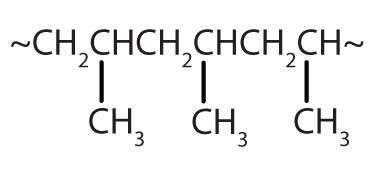

| CH2=CHCH3 |

|

polypropylene | carpeting, bottles, luggage, exercise clothing |

| CH2=CHCl |

|

polyvinyl chloride | bags for intravenous solutions, pipes, tubing, floor coverings |

| CF2=CF2 | ~CF2CF2CF2CF2CF2CF2~ | polytetrafluoroethylene | nonstick coatings, electrical insulation |

Many natural materials—such as proteins, cellulose and starch, and complex silicate minerals—are also polymers. But as natural products they tend to be subject to natural decay processes, breaking down chemically and by the action of microorganisms in the environment.

Practice Questions

Exercise 3.3.2

Section Summary

- Hydrocarbons are non-polar compounds with weak intermolecular forces, leading to low melting and boiling points. They are poorly soluble in polar solvents like water, and their physical properties are influenced by molecular size, with smaller hydrocarbons being gases and larger ones being liquids or solids.

- Hydrocarbons are primarily obtained from geological deposits, such as natural gas and crude oil. These are processed via distillation to separate hydrocarbons based on their boiling points, forming valuable fractions used in various industries, including fossil fuel, plastics, and cosmetics.

- Hydrocarbons, like methane and propane, are essential in industry, but they also pose environmental challenges, such as pollution from oil spills due to their non-polar nature, which makes them difficult to remove from water.

- Alkenes, particularly ethene, undergo polymerization to form large polymers like polyethylene, used in everyday items like plastic bags. Polyethylene’s stable, long-lasting nature raises concerns about plastic pollution and microplastics in the environment.

- Addition polymers, such as polyethylene, polypropylene, and polytetrafluoroethylene, are produced on a large scale and have diverse applications, from packaging materials to specialized products in medical and industrial fields. However, their environmental impact due to resistance to natural decomposition is a growing concern.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structure of DNA

- Describe how eukaryotic and prokaryotic DNA is arranged in the cell

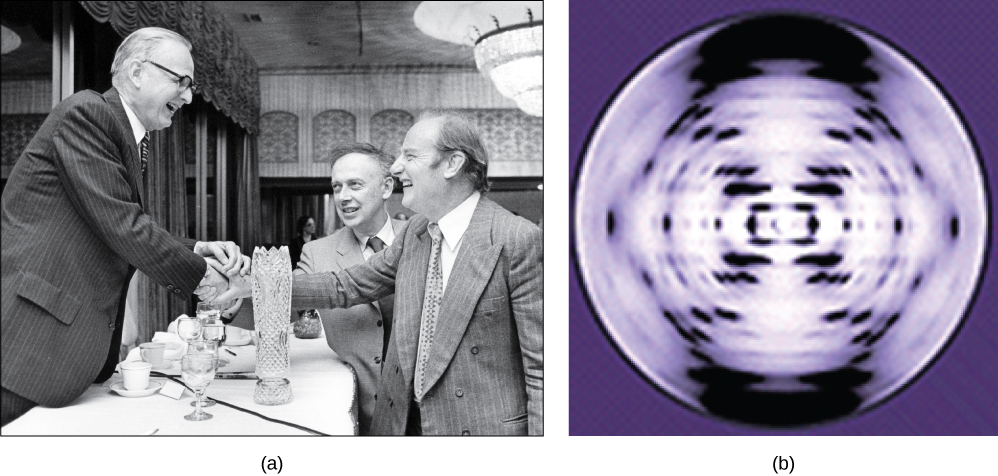

In the 1950s, Francis Crick and James Watson worked together at the University of Cambridge, England, to determine the structure of DNA. Other scientists, such as Linus Pauling and Maurice Wilkins, were also actively exploring this field. Pauling had discovered the secondary structure of proteins using X-ray crystallography. X-ray crystallography is a method for investigating molecular structure by observing the patterns formed by X-rays shot through a crystal of the substance. The patterns give important information about the structure of the molecule of interest. In Wilkins’ lab, researcher Rosalind Franklin was using X-ray crystallography to understand the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick were able to piece together the puzzle of the DNA molecule using Franklin's data (Figure 4.10.1). Watson and Crick also had key pieces of information available from other researchers such as Chargaff’s rules. Chargaff had shown that of the four kinds of monomers (nucleotides) present in a DNA molecule, two types were always present in equal amounts and the remaining two types were also always present in equal amounts. This meant they were always paired in some way. In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their work in determining the structure of DNA.

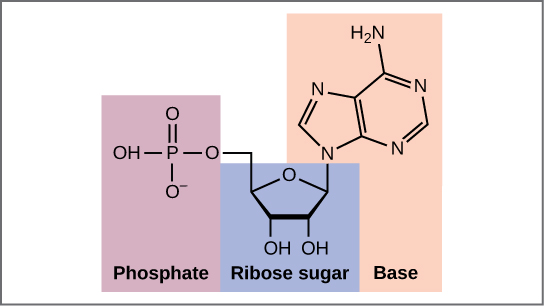

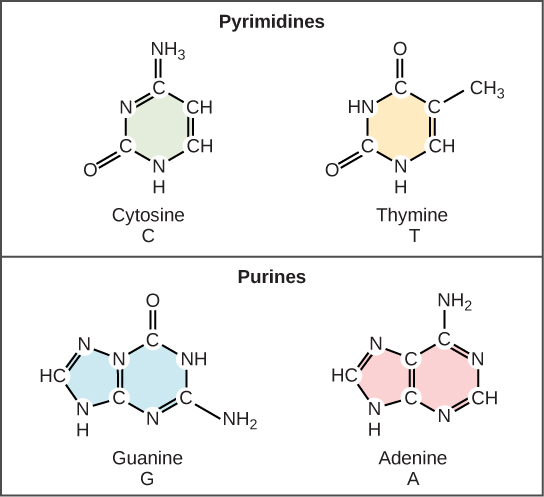

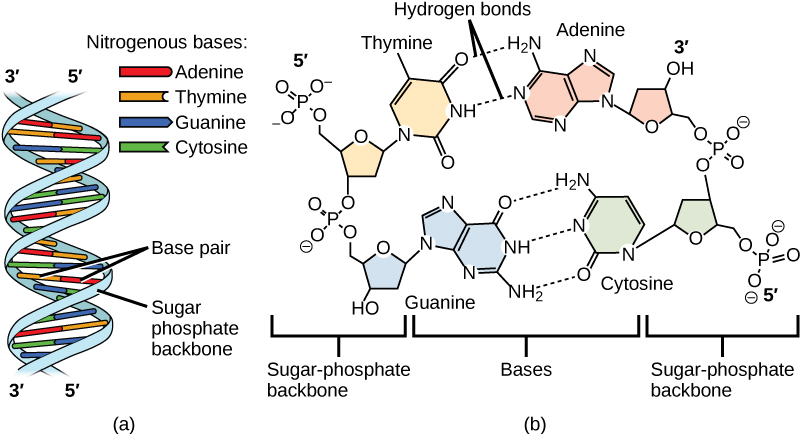

Now let’s consider the structure of the two types of nucleic acids, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). The building blocks of DNA are nucleotides, which are made up of three parts: a deoxyribose (5-carbon sugar), a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base (Figure 9.3). There are four types of nitrogenous bases in DNA. Adenine (A) and guanine (G) are double-ringed purines, and cytosine (C) and thymine (T) are smaller, single-ringed pyrimidines. The nucleotide is named according to the nitrogenous base it contains.

The phosphate group of one nucleotide bonds covalently with the sugar molecule of the next nucleotide, and so on, forming a long polymer of nucleotide monomers. The sugar–phosphate groups line up in a “backbone” for each single strand of DNA, and the nucleotide bases stick out from this backbone. The carbon atoms of the five-carbon sugar are numbered clockwise from the oxygen as 1', 2', 3', 4', and 5' (1' is read as “one prime”). The phosphate group is attached to the 5' carbon of one nucleotide and the 3' carbon of the next nucleotide. In its natural state, each DNA molecule is actually composed of two single strands held together along their length with hydrogen bonds between the bases.

Watson and Crick proposed that the DNA is made up of two strands that are twisted around each other to form a right-handed helix, called a double helix. Base-pairing takes place between a purine and pyrimidine: namely, A pairs with T, and G pairs with C. In other words, adenine and thymine are complementary base pairs, and cytosine and guanine are also complementary base pairs. This is the basis for Chargaff’s rule; because of their complementarity, there is as much adenine as thymine in a DNA molecule and as much guanine as cytosine. Adenine and thymine are connected by two hydrogen bonds, and cytosine and guanine are connected by three hydrogen bonds. The two strands are anti-parallel in nature; that is, one strand will have the 3' carbon of the sugar in the “upward” position, whereas the other strand will have the 5' carbon in the upward position. The diameter of the DNA double helix is uniform throughout because a purine (two rings) always pairs with a pyrimidine (one ring) and their combined lengths are always equal. (Figure 9.4).

The Structure of RNA

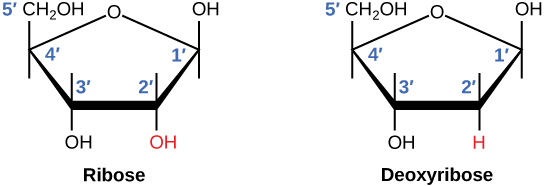

There is a second nucleic acid in all cells called ribonucleic acid, or RNA. Like DNA, RNA is a polymer of nucleotides. Each of the nucleotides in RNA is made up of a nitrogenous base, a five-carbon sugar, and a phosphate group. In the case of RNA, the five-carbon sugar is ribose, not deoxyribose. Ribose has a hydroxyl group at the 2' carbon, unlike deoxyribose, which has only a hydrogen atom (Figure 9.5).

RNA nucleotides contain the nitrogenous bases adenine, cytosine, and guanine. However, they do not contain thymine, which is instead replaced by uracil, symbolized by a “U.” RNA exists as a single-stranded molecule rather than a double-stranded helix. Molecular biologists have named several kinds of RNA on the basis of their function. These include messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and ribosomal RNA (rRNA)—molecules that are involved in the production of proteins from the DNA code.

How DNA Is Arranged in the Cell

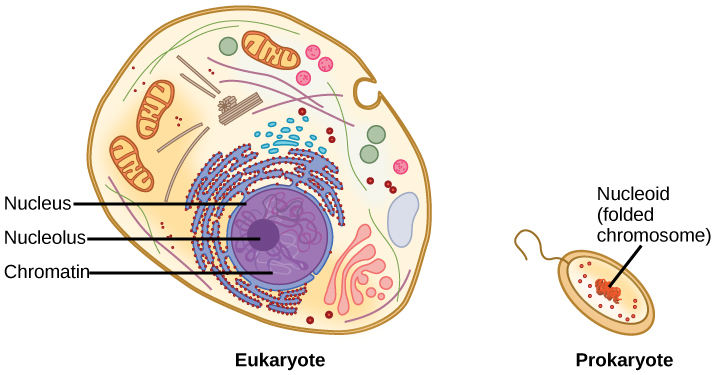

DNA is a working molecule; it must be replicated when a cell is ready to divide, and it must be “read” to produce the molecules, such as proteins, to carry out the functions of the cell. For this reason, the DNA is protected and packaged in very specific ways. In addition, DNA molecules can be very long. Stretched end-to-end, the DNA molecules in a single human cell would come to a length of about 2 meters. Thus, the DNA for a cell must be packaged in a very ordered way to fit and function within a structure (the cell) that is not visible to the naked eye. The chromosomes of prokaryotes are much simpler than those of eukaryotes in many of their features (Figure 9.6). Most prokaryotes contain a single, circular chromosome that is found in an area in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.

The size of the genome in one of the most well-studied prokaryotes, Escherichia coli, is 4.6 million base pairs, which would extend a distance of about 1.6 mm if stretched out. So how does this fit inside a small bacterial cell? The DNA is twisted beyond the double helix in what is known as supercoiling. Some proteins are known to be involved in the supercoiling; other proteins and enzymes help in maintaining the supercoiled structure.

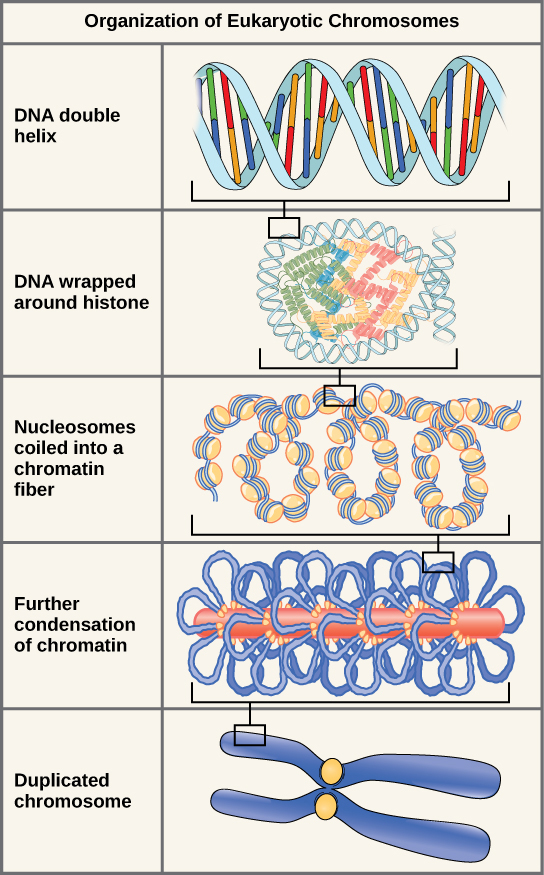

Eukaryotes, whose chromosomes each consist of a linear DNA molecule, employ a different type of packing strategy to fit their DNA inside the nucleus. At the most basic level, DNA is wrapped around proteins known as histones to form structures called nucleosomes. The DNA is wrapped tightly around the histone core. This nucleosome is linked to the next one by a short strand of DNA that is free of histones. This is also known as the “beads on a string” structure; the nucleosomes are the “beads” and the short lengths of DNA between them are the “string.” The nucleosomes, with their DNA coiled around them, stack compactly onto each other to form a 30-nm–wide fiber. This fiber is further coiled into a thicker and more compact structure. At the metaphase stage of mitosis, when the chromosomes are lined up in the center of the cell, the chromosomes are at their most compacted. They are approximately 700 nm in width, and are found in association with scaffold proteins.

In interphase, the phase of the cell cycle between mitoses at which the chromosomes are decondensed, eukaryotic chromosomes have two distinct regions that can be distinguished by staining. There is a tightly packaged region that stains darkly, and a less dense region. The darkly staining regions usually contain genes that are not active, and are found in the regions of the centromere and telomeres. The lightly staining regions usually contain genes that are active, with DNA packaged around nucleosomes but not further compacted.

Section Summary

The model of the double-helix structure of DNA was proposed by Watson and Crick. The DNA molecule is a polymer of nucleotides. Each nucleotide is composed of a nitrogenous base, a five-carbon sugar (deoxyribose), and a phosphate group. There are four nitrogenous bases in DNA, two purines (adenine and guanine) and two pyrimidines (cytosine and thymine). A DNA molecule is composed of two strands. Each strand is composed of nucleotides bonded together covalently between the phosphate group of one and the deoxyribose sugar of the next. From this backbone extend the bases. The bases of one strand bond to the bases of the second strand with hydrogen bonds. Adenine always bonds with thymine, and cytosine always bonds with guanine. The bonding causes the two strands to spiral around each other in a shape called a double helix. Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a second nucleic acid found in cells. RNA is a single-stranded polymer of nucleotides. It also differs from DNA in that it contains the sugar ribose, rather than deoxyribose, and the nucleotide uracil rather than thymine. Various RNA molecules function in the process of forming proteins from the genetic code in DNA.

Prokaryotes contain a single, double-stranded circular chromosome. Eukaryotes contain double-stranded linear DNA molecules packaged into chromosomes. The DNA helix is wrapped around proteins to form nucleosomes. The protein coils are further coiled, and during mitosis and meiosis, the chromosomes become even more greatly coiled to facilitate their movement. Chromosomes have two distinct regions which can be distinguished by staining, reflecting different degrees of packaging and determined by whether the DNA in a region is being expressed (euchromatin) or not (heterochromatin).

Glossary

deoxyribose: a five-carbon sugar molecule with a hydrogen atom rather than a hydroxyl group in the 2' position; the sugar component of DNA nucleotides

double helix: the molecular shape of DNA in which two strands of nucleotides wind around each other in a spiral shape

nitrogenous base: a nitrogen-containing molecule that acts as a base; often referring to one of the purine or pyrimidine components of nucleic acids

phosphate group: a molecular group consisting of a central phosphorus atom bound to four oxygen atoms