3.4.1 Organic Molecules with Heteroatoms: Influence of Hydrogen-bonding and Amine Protonation on Properties

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the influence of heteroatoms on molecular properties

- Compare and contrast intermolecular Interactions

- Describe hydrogen bonding and its effects

- Analyse the effects of amine protonation

The presence of one or a group of heteroatoms on a molecule can have a huge effect on the properties of that substance. Much of the influence relates to the polarity of bonds between these heteroatoms and carbon. Organic structures often include elements from the upper right-hand corner of the periodic table in them. Oxygen, nitrogen and other elements in that part of the table tend to have high electronegativity, producing polar bonds to carbon or hydrogen. When such groups are added to non-polar hydrocarbon structures, they usually impart some degree of polarity to the entire molecule, resulting in a molecular dipole moment.

These intermolecular interactions influence the melting point and boiling point temperatures of compounds, and also influence their solubility in water and other solvents. Compared to alkanes of similar size and structure, amines and alcohols especially (but to some extent, also thiols and ethers) have higher melting and boiling points. So under specific conditions (e.g. normal room temperature and pressure) they will more likely be liquids or solids. They also will tend to have lower vapor pressures, which describes how much of the substance escapes into the air at a given temperature, which correlates in some situations to their odor. Their solubility in polar solvents including water and small liquid alcohols (such as methanol, ethanol or 2-propanol) will be greater. Their solubility in nonpolar solvents, such as toluene, will be less than their nonpolar relatives.

Hydrogen-Bonding

Alcohols and amines (other than tertiary amines) both have the ability to engage in hydrogen bonding interactions. As described earlier, the structural requirements for this phenomenon to exist include:

- hydrogen attached to F, O, N or Cl on a molecule (a highly polarized bond to the hydrogen)

- an electronegative atom with lone pair electrons: F, O, N or another Group 17 element

The -OH and -NH groups on molecules in these families make hydrogen bonding possible, as both hydrogen-bond donor and hydrogen-bond acceptor atoms are present as part of the functional group itself. Hydrogen bond interactions are notably stronger than other dipole-dipole interactions, so these functional groups have especially strong intermolecular attractive forces and the substances have properties to match.

In ethers, polar bonds do exist and dipole-dipole interactions are in play. However, in the ether functional group there is no ability to hydrogen bond completely. The carbon to oxygen bond is polarized, and the oxygen atom on an ether does have lone pair electrons. But there is no hydrogen attached to that oxygen, nor to any other highly electronegative atom.

In thiols we have an architecture that looks like the alcohols, but with sulfur standing in for the oxygen atom of an alcohol. Sulfur is much less electronegative than oxygen and bonds between that atom and hydrogen are much less polar than the oxygen-hydrogen bond of an alcohol. The result is a weak dipole-dipole interaction that can occur in thiols rather than the more powerful hydrogen bond of an alcohol. The properties of thiols are influenced somewhat by the -SH group, but the effect is modest compared to the effect of the hydroxy group on an alcohol.

The effects of intermolecular forces are nuanced, involving both the degree of polarity in functional groups and also the length and shape of the parent hydrocarbon chain itself. But in general, the more functional groups of these types exist in a structure the stronger their influences will be.

Practice Questions

Exercise 3.4.1-1

Exercise 3.4.1-2

Exercise 3.4.1-3

Amine Protonation

In amines, nitrogen is bonded to three other atoms (alkyl groups or hydrogens) and has a lone pair of non-bonding electrons. This lone pair produces a region of electron density on the nitrogen atom, which coupled with the electronegativity of nitrogen produces a partial-negative charge at that location. In samples containing amines, there are intermolecular attractive forces between the amine nitrogen and other partially-positive or positive particles.

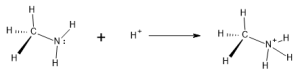

The Bronsted-Lowry theory describes acids as hydrogen ion (proton) donors. The hydrogen ion, H+, is one type of positively-charged particle that can interact with an amine. By associating with the N and utilizing the lone pair for bonding, the amine can convert from an uncharged species to one that carries a positive charge. This takes the H+ from solution and incorporates it into a cation structure, called an ammonium ion:

Even at a neutral pH of 7, enough acid is available in solution for the ammonium ion to predominate. At lower pH (more acidic solutions) it becomes almost the exclusive form.

Since the free, unprotonated amine is able to pick up or ‘accept’ a hydrogen ion in this reaction, the free amine (reactant above) is classified as a base. Various amines will exhibit this behavior to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the specific structures surrounding the amine functional group. For instance, molecules of aromatic amines with nitrogen attached are less commonly in the base form and are thus considered weaker bases.

Ammonium ions exhibit properties that clearly differ from the free, uncharged amine. These ions are more water soluble and can form ionic bonds with various anions to produce ionic substances that can be solid at room temperature. Most small unprotonated amines, by contrast, are liquids.

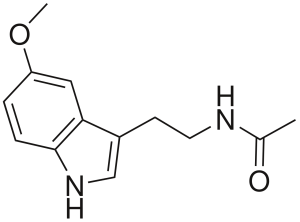

Amines are abundant in nature and appear very commonly in biologically-active molecules, whether those come from natural sources (like plants) or man-made ones (like pharmaceuticals). Liquid medicines are difficult to handle; producers and consumers alike appreciate the long shelf-stability and easy storage of drugs in the form of pills. Whereas an unprotonated amine may be an oily liquid under normal conditions, the corresponding ammonium ion is often part of an ionic solid which can be formed into a tablet. So pharmaceutical companies can use pH adjustment to help them formulate drugs into a better form. Also, the transport of drug molecules in the body will be influenced by water-solubility, so this solubility switch can be important for that reason, too.

Exercise 3.4.1-4

Exercise 3.4.1-5

Provide a description in your own words that explains why a substance that is soluble in water at pH=6 might be insoluble at pH=9.