3.3.3 Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structure of aromatic hydrocarbons

- Recognise and classify aromatic compounds

Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Definition and Applications

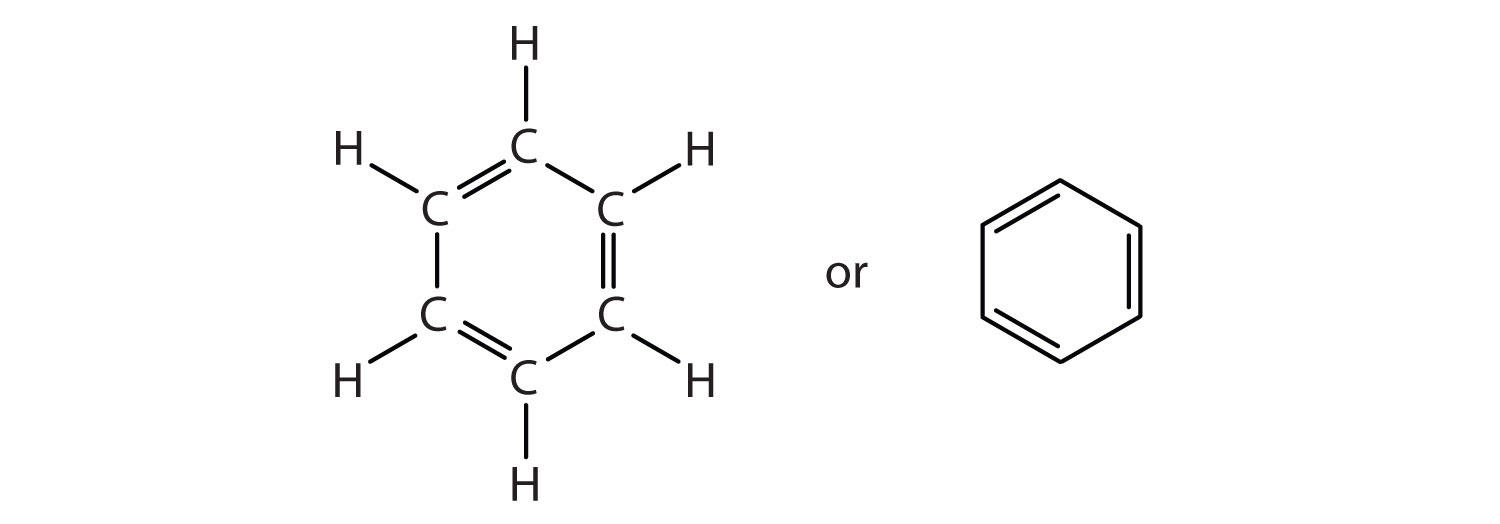

Aromatic hydrocarbons are a class of organic compounds characterised by a ring of carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds. The most well-known aromatic compound is benzene, which consists of a hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms. Aromatic hydrocarbons have unique properties and are found in various applications in both industry and everyday life. Here are some examples of aromatic hydrocarbons, their structures and applications.

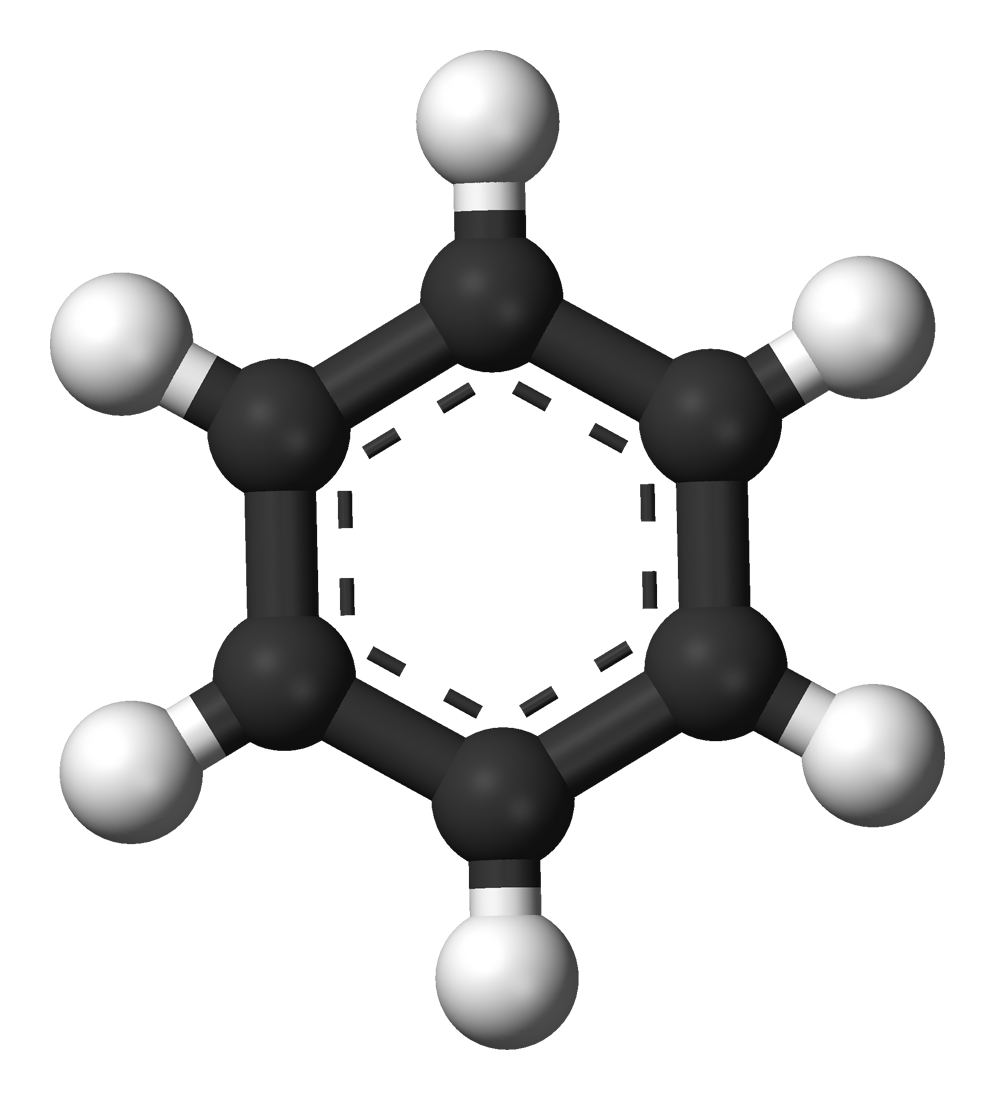

Benzene: A hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms, with each carbon bonded to one hydrogen atom. Applications: benzene is a fundamental building block in the petrochemical industry, serving as a precursor for the production of various chemicals, including plastics, synthetic fibers and pharmaceuticals.

Phenol: a benzene ring with a hydroxyl (-OH) group attached. Applications: phenol is used as an antiseptic and disinfectant. It is also a precursor for the production of plastics, resins and pharmaceuticals.

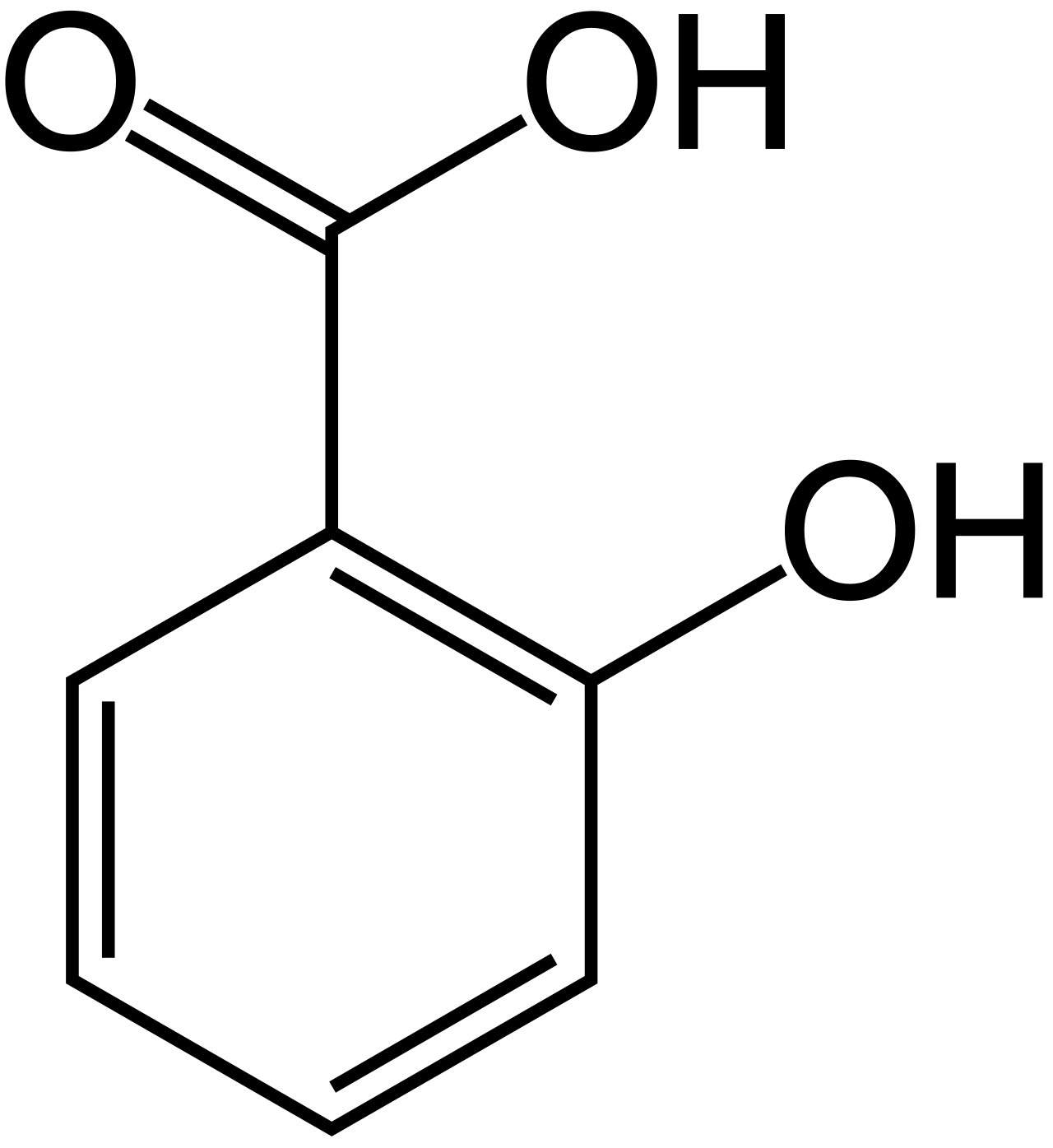

Salicylic Acid: a benzene ring with a hydroxyl group (-OH) and a carboxylic acid group (-COOH) attached. Applications: salicylic acid is used in the production of aspirin and various skincare products due to its anti-inflammatory properties.

Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Aromas

Aromatic hydrocarbons, as the name suggests, are not only a captivating group of organic compounds with distinct chemical properties but also have an intriguing connection to our sensory experiences. These compounds, characterized by a ring of carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds, are responsible for the alluring fragrances and flavors we encounter in our everyday lives.

While the term “aromatic” may initially conjure images of pleasant scents, it is rooted in the rich history of these compounds. In fact, the earliest aromatic hydrocarbon to be discovered was benzene, and was named for its sweet, aromatic smell. However, it is important to note that not all aromatic compounds exhibit pleasant aromas, as the term “aromatic” primarily refers to the specific ring structure they possess.

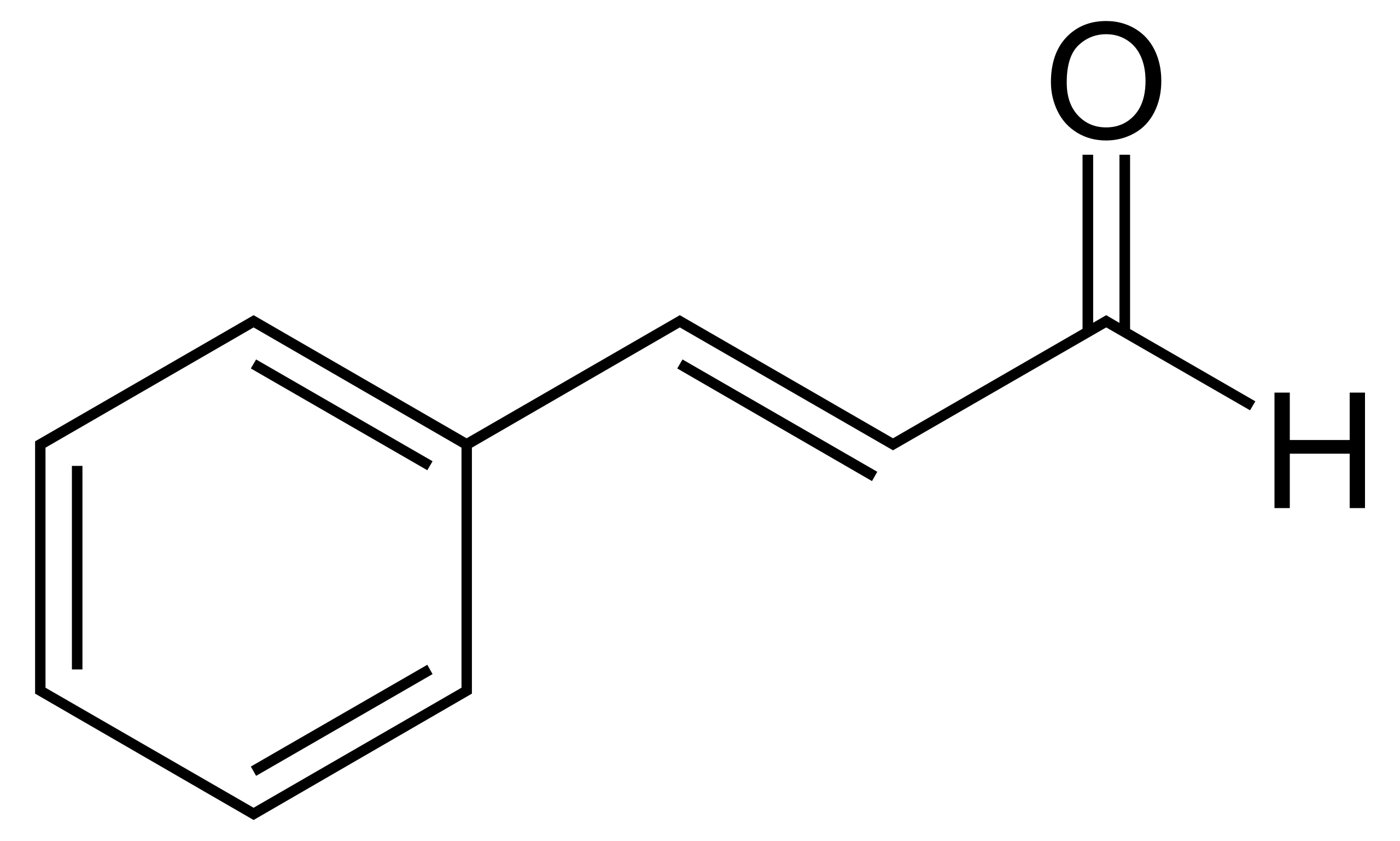

These compounds contribute to a wide array of aromas and flavors. For instance:

Properties of Benzene

We start with the simplest of these compounds, composed of a ring of 6 carbons with one hydrogen attached to each, named benzene. Benzene is of great commercial importance, but its characteristics also include noteworthy negative health effects.

The formula for benzene C6H6 seems to indicate that benzene has a high degree of unsaturation, and it is usually drawn with three double bonds. However, benzene does not react like an alkene. It does not, for example, react readily with bromine, which is a dependable reaction used to identify alkene double bonds in a sample. It is actually quite unreactive.

Benzene is still important in industry as a precursor in the production of plastics (such as polystyrene (StyrofoamTM) and nylon), drugs, detergents, synthetic rubber, pesticides and dyes. It is used as a solvent for such things as cleaning and maintaining printing equipment and for adhesives such as those used to attach soles to shoes. Benzene is a natural constituent of petroleum products, but because it is a known carcinogen, its use as an additive in gasoline is now limited.

Benzene is still important in industry as a precursor in the production of plastics (such as polystyrene (StyrofoamTM) and nylon), drugs, detergents, synthetic rubber, pesticides and dyes. It is used as a solvent for such things as cleaning and maintaining printing equipment and for adhesives such as those used to attach soles to shoes. Benzene is a natural constituent of petroleum products, but because it is a known carcinogen, its use as an additive in gasoline is now limited.Benzene is typically drawn as a cyclic, hexagonal, planar structure of six carbon atoms with one hydrogen atom bonded to each. We can draw the structure with alternate single and double bonds, either as a full structural formula or as a line-bond formula:

Experimental evidence, however, indicates that all six of the carbon-to-carbon bonds in benzene are equivalent. Each has the same bond length and strength as the others, and these bonds are neither as short and strong as typical alkene double-bonds, nor as long and weak as the single bonds we usually see in hydrocarbons.

The chemical properties of benzene do not match alkenes, nor do the measured bond characteristics. It just does not fit in with the alkenes. But aromaticity provides us with an explanation for these facts.

In the aromatic ring system of benzene, valence electrons are shared equally by all six carbon atoms. We describe the electrons are delocalized, or spread out, over all the carbon atoms. It is understood that each corner of the hexagon is occupied by one carbon atom, and each carbon atom has one hydrogen atom attached to it. The alternating double and single bonds around the ring actually are intermediate in length and strength between single C-C and double C=C bonds because of this delocalization.

The reactivity is also affected by this structure, so that atoms are not added to the carbons in the ring. Aromaticity provides a stability to the ring that alkenes do not have.

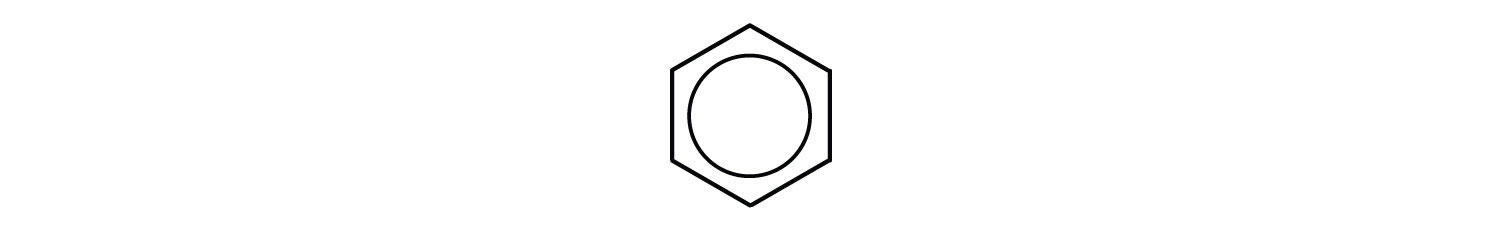

Sometimes, especially in pharmaceutical literature, you will see the benzene ring drawn with a circle inside the hexagon replacing the double bonds, in an attempt to convey the equivalence of the bonds within the ring:

Chemists generally are not satisfied with this representation, however, for reasons we will not discuss here. What is important to take away from the discussion of bonding in benzene is that the drawings we usually make of it do not tell the entire story, and the explanation -called aromaticity, or aromatic character in the benzene ring- is connected to characteristics of compounds containing this feature. If you can spot a benzene ring, you will be able to more accurately predict the properties of substances from their formulas.

Why You Should Not Love the Smell of Gasoline

Once widely used as an organic solvent, benzene is now known to have both short- and long-term toxic effects. It is in gasoline, though in recent decades the amount of benzene in gasoline has been decreased to limit the chance of harmful exposure. It is a volatile liquid that can be taken into the lungs by simply standing nearby. The hoods over gas nozzles are designed to reduce this inhalation exposure for anyone operating a pump.

Inhaling large concentrations of benzene can cause nausea and even death due to respiratory or heart failure, while repeated exposure leads to a progressive disease in which the ability of the bone marrow to make new blood cells is eventually destroyed. This results in a condition called aplastic anemia, in which there is a decrease in the numbers of both the red and white blood cells.

Structure of Aromatic Compounds

Historically, benzene-like substances were called aromatic hydrocarbons because they had distinctive aromas. Today, aromatic compounds include any that contain a benzene ring or have the properties we associate with this group of compounds.

Aromatic compounds often are derivatives of benzene itself with substitution of other atoms and groups for one or more of the hydrogens on the ring. Other aromatic compounds are trickier to identify, but most contain 5 or 6-membered rings composed mostly of carbon, with alternating single and double bonds.

Some representative aromatic compounds and their uses are listed in the table below, where the benzene ring is represented as C6H5.

Table 3.3.3.1: Some Representative Aromatic Compounds

| Name | Structure | Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|

| aniline | C6H5–NH2 | starting material for the synthesis of dyes, drugs, resins, varnishes, perfumes; solvent; vulcanizing rubber |

| benzoic acid | C6H5–COOH | food preservative; starting material for the synthesis of dyes and other organic compounds; curing of tobacco |

| bromobenzene | C6H5–Br | starting material for the synthesis of many other aromatic compounds; solvent; motor oil additive |

| nitrobenzene | C6H5–NO2 | starting material for the synthesis of aniline; solvent for cellulose nitrate; in soaps and shoe polish |

| phenol | C6H5–OH | disinfectant; starting material for the synthesis of resins, drugs, and other organic compounds |

| toluene | C6H5–CH3 | solvent; gasoline octane booster; starting material for the synthesis of benzoic acid, benzaldehyde, and many other organic compounds |

In the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) system, aromatic hydrocarbons such as those above are named as derivatives of benzene. In these structures, it is immaterial whether the single substituent is written at the top, side, or bottom of the ring: a hexagon is symmetrical, and therefore all positions are equivalent.

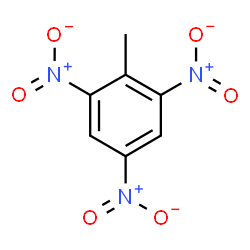

The nitro (NO2) group is a common substituent in aromatic compounds. Many nitro compounds are explosive, for instance 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT).

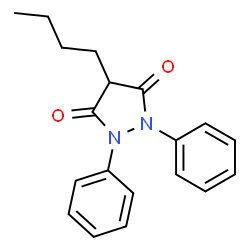

Sometimes an aromatic group is found as a substituent bonded to a non-aromatic entity or to another aromatic ring. The group of atoms remaining when a hydrogen atom is removed from an aromatic compound is called an aryl group. The most common aryl group is derived from benzene (C6H6) by removing one hydrogen atom (C6H5) and is called a phenyl group, from pheno, an old name for benzene.

Phenylbutazone contains two of these phenyl groups. The drug, known commonly as “bute,” is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used in veterinary medicine. Its IUPAC name is 4-Butyl-1,2-diphenyl-3,5-pyrazolidinedione:

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Some common aromatic hydrocarbons consist of fused benzene rings—rings that share a common side. These compounds are called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

All the examples here can be isolated from coal tar. Naphthalene has a pungent odor you may recognize from mothballs. Anthracene is used in the manufacture of certain dyes. Benzo(a)pyrene, also forms during incomplete combustion, so it is a component of soot, auto and diesel exhaust, cigarette smoke and wood smoke. Our bodies metabolize it into compounds that react in well-understood ways with DNA, producing mutations that can develop into cancer. Benzo(a)pyrene is also produced during high temperature cooking, leading to associations between grilled and fried foods, especially meats, and cancer risk.

![Benzo[a]pyrene](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Benzo-a-pyrene.svg/2560px-Benzo-a-pyrene.svg.png)

To Your Health: Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Cancer

The intense heating required for distilling coal tar results in the formation of PAHs. For many years, it has been known that workers in coal-tar refineries are susceptible to a type of skin cancer known as tar cancer. Investigations have shown that a number of PAHs are carcinogens. One of the most active carcinogenic compounds, benzopyrene, occurs in coal tar and has also been isolated from cigarette smoke, automobile exhaust gases and charcoal-broiled steaks. It is estimated that more than 1,000 t of benzopyrene are emitted into the air over the United States each year. Only a few milligrams of benzopyrene per kilogram of body weight are required to induce cancer in experimental animals.

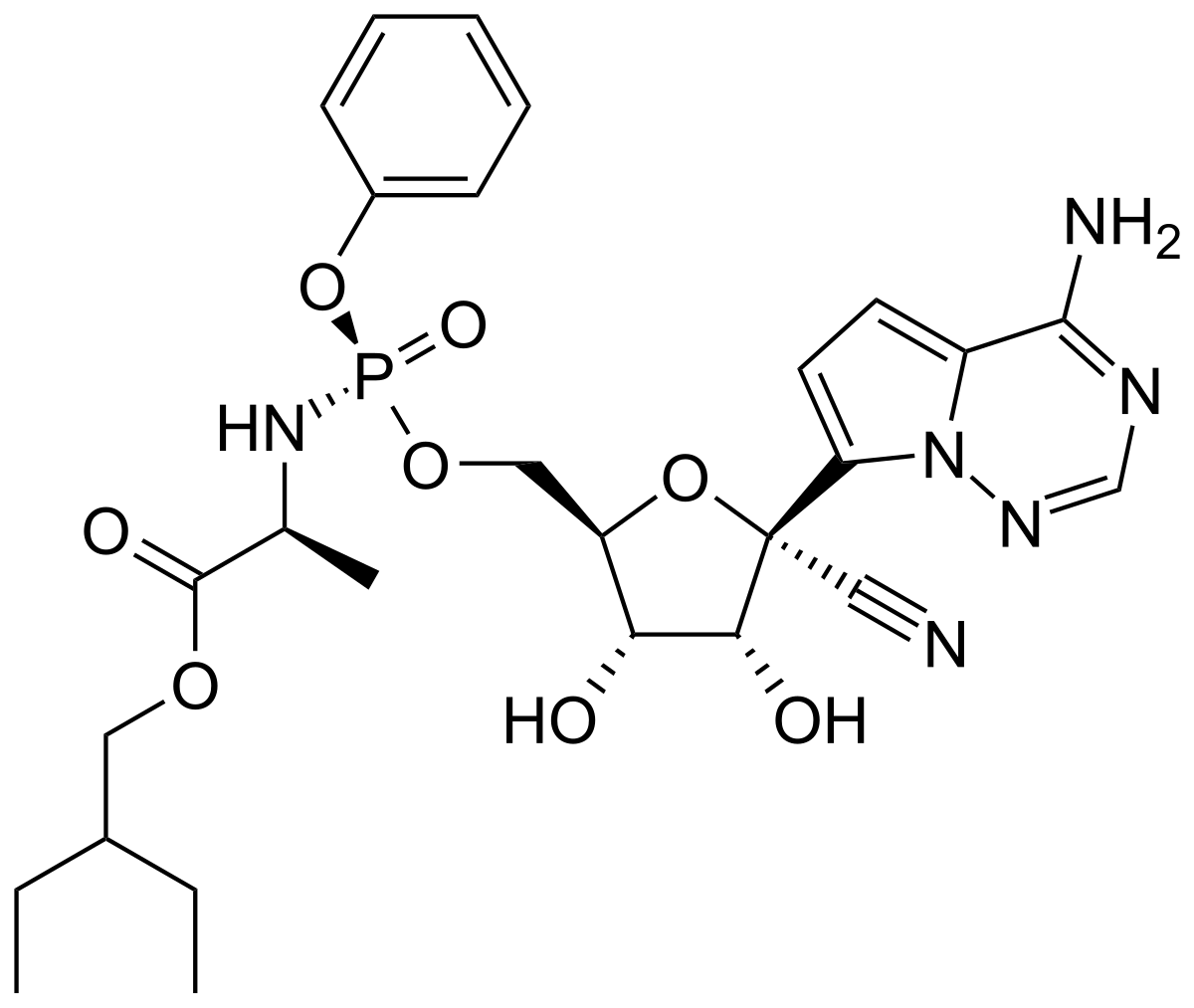

Biologically Important Compounds with Benzene Rings

Substances containing the benzene ring are common in both animals and plants, although they are more abundant in the latter. Plants can synthesize the benzene ring from carbon dioxide, water and inorganic materials. Animals cannot synthesize it, but they are dependent on certain aromatic compounds for survival and therefore must obtain them from food. The essential amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan and vitamins K, B2 (riboflavin) and B9 (folic acid) all contain the benzene ring. Many important drugs also do.