1.4.6 Reaction Energy and Heat

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe endergonic, exergonic, endothermic, and exothermic chemical reactions

- Relate enthalpy change to the abovementioned reactions

- Calculate enthalpy change in a reaction using bond energy

- Describe the concept of Gradient

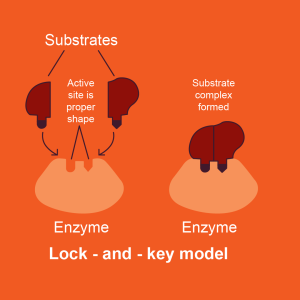

How do enzymes speed up the rate of chemical reactions in cells? The reactants in an enzyme-catalyzed reaction have a special name: substrates. The conversion of substrates to products requires an energy investment. This energy is called activation energy. Activation energy is the energy required to weaken and rearrange the bonds of the substrates to form the products. Enzymes bind substrates at a specific location on the protein called the active site and the active site precisely fits the shape of the substrate(s), like a lock fits a key. The ability of enzymes to only bind its substrates is called specificity. At the active site, the enzyme positions the substrate(s) optimally for the conversion into product(s), thereby decreasing the time needed for the chemical reaction to occur.

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions follow the first law of thermodynamics, like all matter in the universe. The energy for chemical reactions performed by enzymes must come from somewhere. In cells, many chemical reactions are powered by the consumption of chemical sources of energy such as ATP. The energy invested is used to rearrange the chemical bonds within the substrates to form the products. Some of the energy will be converted and dissipated as heat energy (more in the next paragraph). The point is that the energy for chemical reactions already exists in the universe before it is converted to another form of energy. The energy is never destroyed: it simply takes a different form.

For example, when you eat breakfast and run for the bus to come to class, you are transforming the potential energy in the food that you have eaten into kinetic energy while running for the bus. Inside of your cells, chemical reactions rearrange the matter in the food you eat to release the potential energy from those molecules and your muscle cells convert the energy released into kinetic energy (running). However, energy transformations are never 100% efficient. This means that you can never recover 100% of the potential energy stored in the food you eat to convert it to kinetic energy. This is an application of the second law of thermodynamics. A precise statement of the second law of thermodynamics is beyond the scope of this course. However, we can apply it to an understanding of energy transformation by stating that transformations of energy are never 100% efficient because some energy will be dissipated as heat energy. Every single energy transformation or chemical reaction within and outside of cells will result in some of the energy invested or released to be converted into heat energy. The heat energy is not “lost” but it cannot be recovered or used to do additional work. This is not a good nor a bad thing: it is simply the way that our universe works!

Animals that maintain body temperatures different than their surroundings benefit from the second law of thermodynamics, including humans. When we convert the potential energy of food we have eaten into kinetic energy during muscle contraction, every single one of those chemical reactions dissipates some of the energy as heat. The released heat helps to maintain our internal body temperatures at a constant 37°C, regardless of the temperatures of our surroundings.

Thermal Energy, Temperature, and Heat

Thermal energy is kinetic energy associated with the random motion of atoms and molecules. Temperature is a quantitative measure of “hot” or “cold.” When the atoms and molecules in an object are moving or vibrating quickly, they have a higher average kinetic energy (KE), and we say that the object is “hot.” When the atoms and molecules are moving slowly, they have lower average KE, and we say that the object is “cold” (Figure 1.4.6.2). Assuming that no chemical reaction or phase change (such as melting or vaporizing) occurs, increasing the amount of thermal energy in a sample of matter will cause its temperature to increase. And, assuming that no chemical reaction or phase change (such as condensation or freezing) occurs, decreasing the amount of thermal energy in a sample of matter will cause its temperature to decrease.

LINK TO LEARNING

Click on this interactive simulation to view the effects of temperature on molecular motion.

Most substances expand as their temperature increases and contract as their temperature decreases. This property can be used to measure temperature changes, as shown in Figure 1.4.6.3. The operation of many thermometers depends on the expansion and contraction of substances in response to temperature changes.

LINK TO LEARNING

The following demonstration allows one to view the effects of heating and cooling a coiled bimetallic strip.

Heat (q) is the transfer of thermal energy between two bodies at different temperatures. Heat flow (a redundant term, but one commonly used) increases the thermal energy of one body and decreases the thermal energy of the other. Suppose we initially have a high temperature (and high thermal energy) substance (H) and a low temperature (and low thermal energy) substance (L). The atoms and molecules in H have a higher average KE than those in L. If we place substance H in contact with substance L, the thermal energy will flow spontaneously from substance H to substance L. The temperature of substance H will decrease, as will the average KE of its molecules; the temperature of substance L will increase, along with the average KE of its molecules. Heat flow will continue until the two substances are at the same temperature (Figure 1.4.6.4).

LINK TO LEARNING

Click on the PhET simulation to explore energy forms and changes. Visit the Energy Systems tab to create combinations of energy sources, transformation methods, and outputs. Click on Energy Symbols to visualize the transfer of energy.

Matter undergoing chemical reactions and physical changes can release or absorb heat. A change that releases heat is called an exothermic process. For example, the combustion reaction that occurs when using an oxyacetylene torch is an exothermic process—this process also releases energy in the form of light as evidenced by the torch’s flame (Figure 1.4.6.5). A reaction or change that absorbs heat is an endothermic process. A cold pack used to treat muscle strains provides an example of an endothermic process. When the substances in the cold pack (water and a salt like ammonium nitrate) are brought together, the resulting process absorbs heat, leading to the sensation of cold.

Enthalpy

Chemists ordinarily use a property known as enthalpy (H) to describe the thermodynamics of chemical and physical processes. Enthalpy is also a state function. Enthalpy values for specific substances cannot be measured directly; only enthalpy changes (ΔH) for chemical or physical processes can be determined.

The following conventions apply when using ΔH:

-

A negative value of an enthalpy change, ΔH < 0, indicates an exothermic reaction; a positive value, ΔH > 0, indicates an endothermic reaction. If the direction of a chemical equation is reversed, the arithmetic sign of its ΔH is changed (a process that is endothermic in one direction is exothermic in the opposite direction).

-

Chemists use a thermochemical equation to represent the changes in both matter and energy. In a thermochemical equation, the enthalpy change of a reaction is shown as a ΔH value following the equation for the reaction. This ΔH value indicates the amount of heat associated with the reaction involving the number of moles of reactants and products as shown in the chemical equation. For example, consider this equation:

This equation indicates that when 1 mole of hydrogen gas and 1/2 mole of oxygen gas at some temperature and pressure change to 1 mole of liquid water at the same temperature and pressure, 286 kJ of heat are released to the surroundings. If the coefficients of the chemical equation are multiplied by some factor, the enthalpy change must be multiplied by that same factor (ΔH is an extensive property):

Bond Strength

A bond’s strength describes how strongly each atom is joined to another atom, and therefore how much energy is required to break the bond between the two atoms.

It is essential to remember that energy must be added to break chemical bonds (an endothermic process), whereas forming chemical bonds releases energy (an exothermic process). In the case of H2, the covalent bond is very strong; a large amount of energy, 436 kJ, must be added to break the bonds in one mole of hydrogen molecules and cause the atoms to separate:

Bond Strength: Covalent Bonds

Stable molecules exist because covalent bonds hold the atoms together. We measure the strength of a covalent bond by the energy required to break it, that is, the energy necessary to separate the bonded atoms. Separating any pair of bonded atoms requires energy. The stronger a bond, the greater the energy required to break it.

The energy required to break a specific covalent bond in one mole of gaseous molecules is called the bond energy or the bond dissociation energy. The bond energy for a diatomic molecule, DX–Y, is defined as the standard enthalpy change for the endothermic reaction:

The average C–H bond energy, DC–H, is 1660/4 = 415 kJ/mol because there are four moles of C–H bonds broken per mole of the reaction. Although the four C–H bonds are equivalent in the original molecule, they do not each require the same energy to break; once the first bond is broken (which requires 439 kJ/mol), the remaining bonds are easier to break. The 415 kJ/mol value is the average, not the exact value required to break any one bond.

The strength of a bond between two atoms increases as the number of electron pairs in the bond increases. Generally, as the bond strength increases, the bond length decreases. Thus, we find that triple bonds are stronger and shorter than double bonds between the same two atoms; likewise, double bonds are stronger and shorter than single bonds between the same two atoms. Average bond energies for some common bonds appear in Table 1.4.6.1, and a comparison of bond lengths and bond strengths for some common bonds appears in Table 1.4.6.2. When one atom bonds to various atoms in a group, the bond strength typically decreases as we move down the group. For example, C–F is 439 kJ/mol, C–Cl is 330 kJ/mol, and C–Br is 275 kJ/mol.

Table 1.4.6.1 Bond Energies

| Bond | Bond Energy | Bond | Bond Energy | Bond | Bond Energy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H–H | 436 | C–S | 260 | F–Cl | 255 | ||

| H–C | 415 | C–Cl | 330 | F–Br | 235 | ||

| H–N | 390 | C–Br | 275 | Si–Si | 230 | ||

| H–O | 464 | C–I | 240 | Si–P | 215 | ||

| H–F | 569 | N–N | 160 | Si–S | 225 | ||

| H–Si | 395 | 418 | Si–Cl | 359 | |||

| H–P | 320 | 946 | Si–Br | 290 | |||

| H–S | 340 | N–O | 200 | Si–I | 215 | ||

| H–Cl | 432 | N–F | 270 | P–P | 215 | ||

| H–Br | 370 | N–P | 210 | P–S | 230 | ||

| H–I | 295 | N–Cl | 200 | P–Cl | 330 | ||

| C–C | 345 | N–Br | 245 | P–Br | 270 | ||

| 611 | O–O | 140 | P–I | 215 | |||

| 837 | 498 | S–S | 215 | ||||

| C–N | 290 | O–F | 160 | S–Cl | 250 | ||

| 615 | O–Si | 370 | S–Br | 215 | |||

| 891 | O–P | 350 | Cl–Cl | 243 | |||

| C–O | 350 | O–Cl | 205 | Cl–Br | 220 | ||

| 741 | O–I | 200 | Cl–I | 210 | |||

| 1080 | F–F | 160 | Br–Br | 190 | |||

| C–F | 439 | F–Si | 540 | Br–I | 180 | ||

| C–Si | 360 | F–P | 489 | I–I | 150 | ||

| C–P | 265 | F–S | 285 |

| Bond | Bond Length (Å) | Bond Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| C–C | 1.54 | 345 |

| 1.34 | 611 | |

| 1.20 | 837 | |

| C–N | 1.43 | 290 |

| 1.38 | 615 | |

| 1.16 | 891 | |

| C–O | 1.43 | 350 |

| 1.23 | 741 | |

| 1.13 | 1080 |

We can use bond energies to calculate approximate enthalpy changes for reactions where enthalpies of formation are not available. Calculations of this type will also tell us whether a reaction is exothermic or endothermic. An exothermic reaction (ΔH negative, heat produced) results when the bonds in the products are stronger than the bonds in the reactants. An endothermic reaction (ΔH positive, heat absorbed) results when the bonds in the products are weaker than those in the reactants.

The enthalpy change, ΔH, for a chemical reaction is approximately equal to the sum of the energy required to break all bonds in the reactants (energy “in”, positive sign) plus the energy released when all bonds are formed in the products (energy “out,” negative sign). This can be expressed mathematically in the following way:

Consider the following reaction:

This excess energy is released as heat, so the reaction is exothermic.

EXAMPLE 1.4.6.1

Using Bond Energies to Calculate Approximate Enthalpy Changes

Methanol, CH3OH, may be an excellent alternative fuel. The high-temperature reaction of steam and carbon produces a mixture of the gases carbon monoxide, CO, and hydrogen, H2, from which methanol can be produced. Using the bond energies in Table 1.4.6.2, calculate the approximate enthalpy change, ΔH, for the reaction here:

First, we need to write the Lewis structures of the reactants and the products:

From this, we see that ΔH for this reaction involves the energy required to break a C–O triple bond and two H–H single bonds, as well as the energy produced by the formation of three C–H single bonds, a C–O single bond, and an O–H single bond. We can express this as follows:

Check Your Learning

Ethyl alcohol, CH3CH2OH, was one of the first organic chemicals deliberately synthesized by humans. It has many uses in industry, and it is the alcohol contained in alcoholic beverages. It can be obtained by the fermentation of sugar or synthesized by the hydration of ethylene in the following reaction:

Using the bond energies in Table 1.4.6.2, calculate an approximate enthalpy change, ΔH, for this reaction.

ANSWER:

–35 kJ

Gradient

Sometimes solutes are found at uneven concentrations within a solution. The concentration of a solute in a solution is the amount of solute per volume, usually measured in moles per litre or molarity (M) or as the percent mass of solute per volume (%). If the concentration of a solute is non-uniform within a solution, this results in a concentration gradient within that solution. A gradient refers to a difference in the distribution of matter within a system.

Concentration gradients are a form of chemical potential energy. This is because solutes tend to move from high concentration to low concentration. This phenomenon is known as diffusion and you will discuss it further in lab and lecture. Solutions move toward even mixing or equilibrium. Therefore, a concentration gradient within a solute represents a chemical potential where the molecules have the potential to move to an area of lower concentration within the solution. A potential refers to a difference in the distribution of energy within a system.

Ions form a chemical concentration gradient within a solution but they also bear charges. If the charge distribution within a solution is non-uniform, this results in an electrical gradient. Electrical gradients result in one part of the solution being more negatively charged and another part of the solution being more positively-charged. The resulting non-uniform distribution of charge is an electrical potential because negative charges tend to move toward areas of positive charge and vice versa. Ion gradients represent both a chemical concentration gradient AND an electrical gradient. The sum of these two gradients is collectively referred to as an electrochemical gradient and the difference in chemical and electrical energy within that system is called an electrochemical potential.

Electrochemical gradients and the resulting electrochemical potentials are biologically important. Cells actively maintain electrochemical gradients across their membranes to ensure that electrochemical signals can be sent from the brain, along nerves, to muscle and gland cells. Electrochemical gradients across cell membranes ensure that cells can generate energy. You will have a fuller understanding of these processes by the completion of this course.

In a solution, equilibrium is the even mixing of solutes within a solvent. Solutes tend to move from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration, leading to even dispersal of the solute in solution.

Chemical reactions may also be in equilibrium. What does this mean?

Chemical reactions can occur in two directions: forward and reverse. For example, the formation of carbonic acid is endergonic in the forward reaction and exergonic in the reverse reaction. Chemical equilibrium occurs when the forward reaction and the reverse reaction occur at the same rate. Special conditions are required to achieve chemical equilibrium for each reaction. You will learn more about chemical equilibrium in the future chapters.

Inside of cells, most chemical reactions do not occur in conditions that favour chemical equilibrium. The special environment maintained within the cell ensures that some chemical reactions are irreversible, meaning that the reaction performed cannot convert the products back into the reactants. Most metabolic reactions are irreversible reactions. However, cells may change the intracellular environment to increase the rate of a reversible reaction in a particular direction. This is also true at the tissue, organ, and organ system level. For example, you will learn about how red blood cells, blood, and the respiratory system cooperate to ensure that carbon dioxide is effectively removed from the blood in a timely manner during our discussion of the respiratory system.

Cells change the conditions within the cell to affect whether certain chemical reactions will occur and how fast they will occur. This phenomenon is called regulation, and you will examine this topic in nearly every lecture of this course.

Section Summary

- Energy is the capacity to do work. It can be neither created nor destroyed and every energy transformation dissipates some energy as heat energy.

- A gradient is an uneven distribution of matter within a system.

- A potential is an uneven distribution of energy within a system.

- Cells use both chemical and electrical gradients, or electrochemical gradients, to store energy and prepare for the many energy transformations that sustain life.

- Chemical reactions rearrange matter:

- Endergonic chemical reactions require energy input to make/break bonds.

- Exergonic chemical reactions release energy as bonds are made/broken.

- Chemical reactions achieve equilibrium when the rate of the forward and reverse reactions is approximately the same:

- The intracellular environment may favour one direction, but the intracellular environment can change.

Energy-requiring

Energy-releasing

Stored energy

Inside of the cell