3. Field Education and Covid-19: How RMIT responded to a crisis within a crisis.

Margareta Windisch and Rob Cunningham

This chapter reflects on RMIT Social Work’s approach to managing student placements during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020-21. The purpose of this chapter is to highlight the challenges experienced, the strategies implemented to manage these challenges, and lessons learnt by the RMIT Field Education team.

Background: Covid-19 and Melbourne

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a global impact; over 260 million people have contracted the virus and over 5 million people have died (WHO, 2021). Social Work Field Education programs throughout the world have continued to operate during the pandemic, however, just like the impact of Covid-19 on a wider global scale, how Field Education programs have been impacted by the pandemic has been influenced by geographic location. The impact on Field Education programs has not only been influenced by the country the program is based in, but also the state and region within the country. As an example, in Australia, the state of Victoria accounts for 58% of the total Covid-19 cases in the country, and 66% of total deaths (Department of Health, 2021). Victoria’s capital city of Melbourne has experienced six lockdowns for a combined total of 262 days throughout 2020-21. Table 1 details the number, dates and duration of Melbourne lockdowns in 2020-2021.

Table 1 Melbourne Covid-19 Lockdowns 2020-2021

|

Lockdown |

Dates |

Total Days |

|---|---|---|

|

Lockdown 1 |

March 30 – May 12, 2020 |

43 |

|

Lockdown 2 |

July 8th – October 27, 2020 |

111 |

|

Lockdown 3 |

February 12 – February 17, 2021 |

5 |

|

Lockdown 4 |

May 27 – June 10, 2021 |

14 |

|

Lockdown 5 |

July 15 – July 27, 2021 |

12 |

|

Lockdown 6 |

August 5 – October 22, 2021 |

77 (262 days in all) |

At the time of writing this chapter the people of Melbourne have endured more days in lockdown (262) than any other city in the world (Boaz, 2021). State imposed lockdown measures included strict stay at home orders, restrictions on economic and recreational activities, limitations on travel and movement and the imposition of nighttime curfews. These lockdowns required significant sacrifices and a major reorientation of personal, professional, and economic life. The impact has been manifold and often traumatic, with major implications for the people of Melbourne, including students and university staff, and the social services sector.

It is important to situate our experience within this unique locality-based context. How RMIT Social Work Field Education was able to provide students with quality field experience within a global pandemic, in the most locked down city in the world, should be of interest to Social Work Field Education programs globally. This knowledge can be used by Field Education teams to support and maintain student placements within a crisis.

Field Education

Field Education is considered a ‘distinctive pedagogy ‘of social work education and is considered one of the most memorable components of a student’s learning experience (Egan et al. 2018). It is where teaching and learning leave the controlled and formal classroom environment and students are confronted with the messiness of real-life scenarios in the workplace; or ‘where the rubber hits the road. In other words, Field Education plays a critical role in developing social work students’ professional identity, their competencies and understanding of ethical practice (Bogo 2015).

RMIT Social Work, like many other social work programs nationally and internationally, has faced challenges in sourcing sufficient field education placements due to a highly competitive tertiary education market, characterised by an ever-increasing student cohort and a growing number of social work schools vying for placement opportunities. Neoliberalism and decades’ long structural neglect of the welfare sector has further compounded the pressure on universities and organisations to provide adequate staff resources to ensure successful placement provision (Egan, Hill & Rollins 2020).

While RMIT has a rich 45 year history in collaborating with the social work industry to provide student placements, the past decade has seen a persistent focus in developing these relationships (Egan, 2018). This has resulted in the current RMIT Social Work Field Education Partnership Model, whereby partner agencies provide a minimum of ten placements per year. The partnership includes financial support and the provision of off-site supervision by RMIT, training and professional development sessions, as well as building research and project capacity. A partnership reference group was also set up to ensure a reciprocal and active relationship is maintained between RMIT and industry partners. This reference group has input into placement provision, monitors and evaluates student placements to ensure they are adaptive to changing circumstances (Egan, 2018). The partnership model has been instrumental in providing a stable number of social work placements each year that meet AASW accreditation requirements, as well as providing a quality and rich learning experience for students. The partnership model has proved vital in the sustainability of the RMIT Social Work Field Education Program in a competitive market.

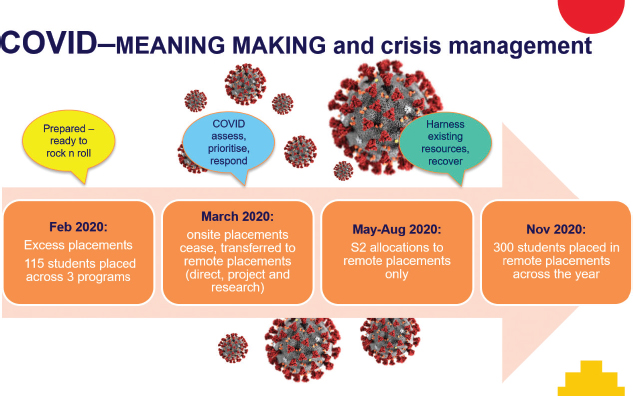

This partnership model combined with a crisis management approach proved critical in helping us contain the Covid-19 pandemic fallout, navigate through the significant challenges posed by associated restrictions, and offer viable placement opportunities for all students. Figure 1 outlines the RMIT pandemic responses during 2020.

The RMIT field education team started 2020 with a placement surplus, which was reflective of our well-established industry links and a dedicated Professional Practice Coordinator who has been able to nurture existing partnerships and build new relationships with agencies. By the time the Victorian state government declared a ‘state of emergency ‘on March 16, 117 students across three programs (BSW, BSW/Psych and MSW) had started placements. The imposition of a broad suite of Covid-19 pandemic related restrictions severely restricted most agencies ability to continue onsite service delivery, including the capacity to host students. While our partners were busily working out how to best navigate and adapt to this unprecedented situation, RMIT university had to develop new safety procedures for its student cohort engaged in field education activities. The combination of emergency restriction, agency pressures and RMIT’s duty of care to its students meant all semester 1 2020 onsite placements ceased and a decision was made to offer semester 2 placements on a remote basis only. All up RMIT placed 305 students during 2020. Table 2 provides an overview of the 305 student placements offered in 2020.

Table 2 2020 Social Work Placements at RMIT

|

Placement Program, Supervision and Mode. |

Number of Students |

|---|---|

|

Total Number of Placements in 2020 |

305 |

|

Master of Social Work |

117 |

|

Bachelor of Social Work |

188 |

|

Field Education 1 (1st Placement) |

156 |

|

Field Education 2 (2nd Placement) |

149 |

|

Onsite Supervision |

156 |

|

Offsite Supervision/Liaison |

151 |

|

Face to face placement |

17 |

|

Remote, home-based placement |

247 |

|

Hybrid – combination of face to face and remote placement. |

18 |

|

Internal RMIT Projects. |

10 |

All semester 1 placements had to be assessed on their potential to be conducted remotely (work from home) and be supported sufficiently as not to jeopardise viability and integrity. Placements were either ended or interrupted where a transfer to a remote mode of operation was not an option.

This was an extremely complex and labour-intensive period, characterised by a ‘stop and start’ uncertainty and confusion resulting from shifting processes, and continuous negotiations across all stakeholders. The rapid development of new processes and resources combined with authenticity, transparency and increased frequency in communication became a top priority to guide us through the constantly shifting pandemic terrain.

We created new information resources for students clarifying Covid-19 impacts on Field Education (Covid-19 Modules) and updated the Social Work Field Education Hub – an external facing communication site for industry partners. These online spaces provided essential information and resource repositories and critical tools in facilitating the successful management of high levels of uncertainty. Regular newsletters, emails, and frequent drop-in sessions and Question and Answer (Q&A) sessions for students proved to be invaluable support mechanisms and helped alleviate stress and anxiety. The Field Education (FE) team were not afraid to take some risks, think and act outside the box, take up new opportunities in the unfamiliar remote placement space and create new parentships. These innovative practices are detailed within other chapters of this book.

Acting with care and being accessible were vital elements in our crisis management approach. Acknowledging the pain caused by the pandemic, the significant individual challenges experienced, hard work, and successes achieved; helped in overcoming hesitancy and reluctance regarding online learning opportunities.

When Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews declared a state of disaster on August 2, 2020, our field education team was well set up and ready to support its large semester 2 student cohort through their remote placements. This was consistent with RMIT policy to only support remote placements.

Phase Two: 2021

Melbourne was heavily impacted by Covid-19 in 2021, again experiencing the highest level of cases and lockdown days in Australia (Department of Health, 2021). However, our 2020 experience allowed us to plan and respond to the continued challenges and changing circumstances the pandemic presented in 2021, allowing for rapid and targeted responses to changes in emergency measures affecting placements. The successful strategies of 2020 were again implemented. A focus on clear and frequent communication with key stakeholders was critical in preparing everyone for the potential of further lockdowns and changes to placement modes. The frequent communication also allowed for risk assessments and Covid-19 exposure sites to be adequately managed by the Field Education team. Collaborative relationships with partner agencies was again a priority and allowed enough placements to be sourced and for these placements to be adaptable to any potential lockdowns. Off-Site supervision/Liaison was again important in providing students with tailored support and supervision.

Table 3 2021 RMIT Field Education Placements

|

Placement Program, Supervision and Mode. |

Number of Students |

|---|---|

|

Total Number of Placements in 2021 |

400 |

|

Master of Social Work |

207 |

|

Bachelor of Social Work |

193 |

|

Field Education 1 (1st Placement) |

216 |

|

Field Education 2 (2nd Placement) |

184 |

|

Onsite Supervision |

206 |

|

Offsite Supervision/Liaison |

199 |

|

Face to face placement |

197 |

|

Remote, home-based placement |

33 |

|

Hybrid – combination of face to face and remote placement. |

197 |

|

Internal RMIT Projects. |

6 |

Table 3 provides an overview of the 400 student placements offered in 2021. This demonstrates the Field Education team was able to provide a 23% increase in the number of placements in 2021 compared to 2020, with most placements returning to at least some onsite experience for students (over 90%). This was achieved despite the extended lockdowns in Melbourne throughout the year, suggesting the experience and lessons learned in 2020 provided the program with added resilience and adaptability to meet the ongoing challenges of Covid-19.

Weathering the storm: valuing interdependence

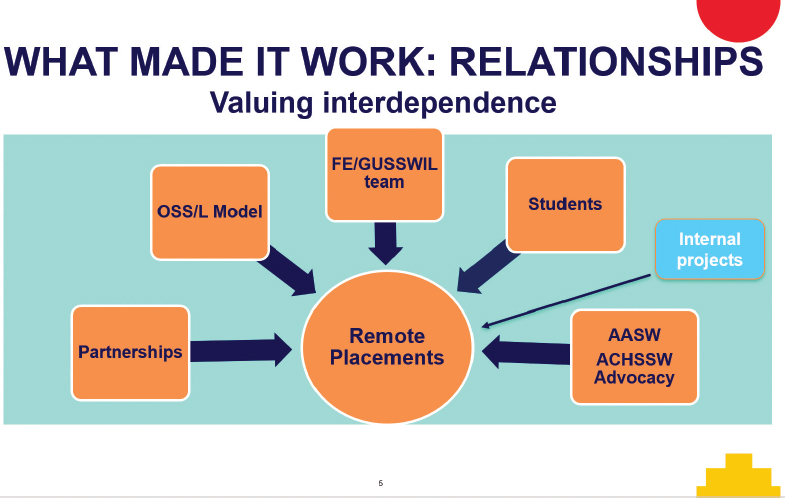

We were able to meet our challenges through harnessing our existing resources and working in close collaboration with all our stakeholders. Figure 2 provides an overview of the key relationships leading to RMIT’s Field education response to the pandemic.

Figure 2: What made it work: Relationships

1. Partnerships: Our philosophical approach to our industry partners of reciprocal respect, goodwill and shared values was fundamental and provided a solid foundation to weather the crisis. It allowed us to work imaginatively and innovatively and collaborate closely to transition from onsite to remote placements. This included the developing of creative responses of service delivery such as telehealth, online digital literacy initiatives or specific project and research-based placements. Please see other chapters within this book for examples of these collaborative and innovative practices

2. RMIT projects: The RMIT social work department also responded expediently to the crisis by fast tracking the development of some projects to capture students whose placements had ceased. The strengths of the partnership model meant that we had to replace only a handful of placements with internal RMIT projects to meet our demand. Internal RMIT projects made up 4 % of total placements across 2020-21.

3. Offsite Supervision/Liaison Model: The partnership model was complemented by a cohesive team of dedicated and experienced RMIT staff providing offsite supervision and liaison. The off-site supervision model used by RMIT incorporates the use of an external social work supervisor provided by RMIT, when an agency is unable to provide a qualified social work practitioner to undertake this role. This is a dual role in which the external supervisor also undertake the university liaison role. This model uses both individual and group supervision sessions. We set up fortnightly peer catchups with staff undertaking these roles as an opportunity to support and share ideas on how to best manage placements and guide students in this unfamiliar terrain. Student group supervision took on extra importance as it allowed students to engage in group learning, substitutes for incidental learning that happens face to face and provided much needed connection during isolation periods. Feedback from students and partner agencies suggested the role of the offsite supervisor and the group supervision format was critical during lockdowns, providing added support to students isolated from an onsite team environment. This links to previous research conducted on the offsite model which demonstrated students valued the peer network, debriefing, critical reflection and supportive relationships developed during group supervision with an external social work supervisor (Egan, David & Williams, 2021).

4. Field Education Team: The Field education team, comprising of academics and professional staff, already had well established structures which allowed for the redevelopment of existing and creation of new processes in very short timeframes. We increased the frequency of team meetings, allowing for important information sharing and problem solving and used a collaborative and collective approach that was inclusive rather than top down.

5. ACHSSW and AASW advocacy: Advocacy from the Australian Council of Heads of Schools of Social Work (ACHSSW) with the Australian Association of Social Work (AASW) proved instrumental in allowing for an effective, flexible and empathetic response to the challenges the Covid19 crises posed for field education. The AASW’s Covid-19 Parameters (AASW, 2020) response approved significant variations to their social work program accreditation standards which helped prevent the collapse of field education in states most affected by the pandemic and related restrictions. Student placements simply could not have continued without this response. As we enter 2022 it is important the AASW’s Covid-19 Parameter response continues while Field Education teams continue to manage the ongoing challenges of this pandemic.

6. Students: A special mention must go to our student cohort, who valiantly rose to the challenge. The Covid-19 crisis hit students exceptionally hard, with many suffering significant financial hardships, as their casual jobs literally disappeared overnight. The sudden shift to online learning, a severe contraction of social life and connectedness combined with pandemic related anxieties, compounded already existing experiences of inequality and increased stress levels significantly. As one placement student put it “… there was so much to manage; loss of work, trying to manage income, isolation at home, no-one to have morning tea with like a normal placement.” Students demonstrated high levels of adaptability and flexibility as they learned how to navigate the complexities and demands of remote placements. Many students were able to put their technological savviness and digital literacy to good use on placement, supporting agencies and services users alike in the pivot to online platforms for service delivery and engagement.

Conclusion:

The Covid-19 pandemic required Field Education programs to demonstrate innovative and collaborative practice in the following ways:

1. Learning as co-creation – There were many examples of Field Education students using their existing skills (particularly online and technology skills) to teach Field Educators and partner organisations. This resulted in a move away from vertical knowledge transfer to a more collaborative learning environment. Please see specific example of this in the various agency specific Chapters.

2. Democratising work/study opportunities: Working and learning online has allowed for the mainstreaming of flexibility and new equitable ways to learn. For example, feedback from staff and students living with a disability suggested the online space offered more opportunities to engage in work and learning experiences. This was supported by regional students and staff who also suggested online work had opened more opportunities for their participation.

3. Extending service delivery: The extension of online technology and methods of service provision allowed the continuation of services to many client groups. These modes of service delivery were also used for individual and group supervision.

4. Committing to relationships: Fostering of reciprocal relationships between universities and committed industry partners.

5. Advocating for justice: For ongoing and increased flexibility to respond effectively to crises; continuous engagement with AASW, industry bodies and government.

It is important the learnings created through the Covid-19 pandemic are taken forward into future practice. The RMIT Social Work Field Education Program will now focus on ensuring these innovative practices are adopted and nurtured in the long term.

While the pandemic has created new opportunities in social work field education, it is also important to note the costs of Covid-19, which have been seismic, traumatic, and profound, with the most disadvantaged community sectors and members hardest hit. It has also created significant ruptures and changes within field education. For the RMIT Field Education team the impact of the pandemic, and the workload it has created has been severe. Ensuring the continuation of student placements, working with industry partners to adapt placements, the increased compliance and risk management processes, providing emotional support and care to students; all took an emotional and physical toll on the Field Education team. The cumulative stress over the period of two years has been significant for the field education team, students and our industry partners.

This chapter has detailed the experiences of the RMIT Field Education team in managing student placements through the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. We have documented the importance of crisis management, including frequent and clear communication to all Field Education stakeholders. The importance of strong and innovative relationships with industry partners was also highlighted, as was the importance of the off-site supervision/liaison role in providing additional support to students in this crisis. We also established a field education team that is adaptive to the changing circumstances of the pandemic, as well as being responsive to the needs of students was vital in managing the program throughout this period. Finally we have outlined how the pandemic has created opportunities for Field Education, such as co-creation of the learning environment, increased flexibility and equity for students, and the creation of new and innovative placement settings.

It is important to note this chapter is a reflection of the first two years of the Covid-19; the pandemic is far from over and will continue to have global consequences, as well as impacting on social work field education. It is therefore important to further examine field education in this context, not just as this pandemic evolves, but also for future pandemics, crises and emergencies.