Colour dyes: a (very) short history of dyes from around the world

Image by Thelmadatter via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Throughout history and across cultures and continents, dyes have been used for thousands of years to colour materials. Many dyes were originally used to colour textiles – fibre-based materials such as threads, yarns or fabrics that are woven or knitted and made from plant or animal fibres, such as cotton, linen, flax, hemp, grasses, wool, silk, human hair, etc. Dyes were also used to stain wood, pottery, and animal hides.

Dyes are different to pigments because they are soluble (they can dissolve in water) and traditionally were mostly made from organic substances (plants or animals). Dyeing processes can also be more complex than working with paint pigments because the dye must be absorbed and held fast in the material it is colouring. Different techniques were developed over time to bind dye colours with the material to prevent the dye from washing out or fading too quickly.

Many of the discoveries for improving dyes throughout history relate to developing chemical processes for creating more vibrant colours, and for creating colours that last longer, which includes lightfastness and colourfastness properties, and the ability to bind with materials they are absorbed into. The development of fixatives (known as mordants) was a necessary innovation to prevent dyes from being washed out of textiles, enabling long-lasting colour. Some methods were more successful than others, and evidence has been discovered of ancient textiles that still have some colour from dyeing.

Ancient discoveries

Archeologists have discovered examples of dyed textiles that date back to Neolithic times. One example is from around 10,000 BCE, in the Timna Valley, South Israel, where ancient copper and ore mining sites have been uncovered. [1].

Another archeological example is the discovery of 30,000 year-old flax textiles found in Dzudzuana cave, located in the foothills of the Caucasus region in Georgia, Europe. The flax was dyed in many different colours, including “yellow, red, blue, violet, black, brown, green and khaki.”[2]

The Silk Road was an ancient trading route that ran from the Roman civilisation on the Mediterranean, through Afghanistan, the Levant and India, to the Xi’an region in northern China. This route was over 6,400 kilometres long! It was a pathway for trading between east and west cultures in many products such as spices, textiles, and precious metals. It was also the pathway for trading dyestuffs and knowledge about dyeing processes.[3]

Because of the Silk Road, and ancient maritime trade routes, many cultures had access to dyes that were not made from plants native to particular areas – including indigo, woad, saffron, madder, and safflower. Here are some (very) short stories about the history of selected dyes from locations around the world:

China and Japan

In ancient Chinese silk production, colouring the thread began right from the first stage when the silkworm creates silk thread to form a cocoon. By feeding the silkworm white garden mulberry or wild mulberry leaves, the silk produced could be either white or yellow. Creating different coloured silk threads often involved bleaching it first by boiling threads in the ash of Lian tree fruit. Blue dye was made by fermenting indigo, black from iron vitriol, red from madder root or safflower, and yellow from Jinzi fruit.

The Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) Dynasties in China created very detailed records of types of dye and the dyeing methods and processes used. These records are an important historical resource for understanding how different natural substances were used to achieve the diverse and vibrant colours we associate with Chinese silk and other textiles.[4]

Japan has a long tradition of dyeing materials such as textiles, paper and wood, going back 2000 years. There are also records going back to the 7th century that document textiles dyed with red, blue, and other colours. These dyes were made from natural materials native to Japan, but also those that came via the Silk Road, maritime trade, and from the influences of Chinese and Korean textiles and dyeing methods. Evidence exists of textiles dyed with vermilion, sappanwood, cinnamon and Gunjyo – a blue pigment made from mining a mineral ore that had copper in it.[5]

Japan is also known for its indigo dye and textiles called Aizome. Indigo was introduced to Japan in the Heian period around the 7th Century CE. Since that time, techniques for creating indigo textiles have developed to become culturally significant, and Japanese indigo textiles are highly valued around the world.

South-East Asia

Although Batik (wax resistance dyeing) is historically found in many places around the world, its origins in Java, Indonesia, are significant. Indonesian Batik was recognised by UNESCO in 2009 and placed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Watch this video to learn more about the history and techniques of Batik:

India

India’s ancient history of dyes is significant. Not only did they produce many dyes and techniques for achieving vibrant colours, but they also developed mordants and processes to fix the dyes, which were closely guarded secrets for a long time. Indian textiles were highly prized across Europe. The name “Indigo” is a reference to India, where the plant Indigofera Tinctoria was grown, although it was also found in much of Asia and parts of Africa too.

The ancient Sanskrit texts, known as the Vedas (meaning “knowledge”), are the oldest Hindu texts known to exist – from around 1500-500 BCE. These contain details about textiles and clothing worn at different times of the year or at religious ceremonies, with reference to multiple colours. From these texts, we know that Indian dyeing techniques for creating vibrantly coloured fabrics existed around that time.

Tie-dye, known as Bahndani (meaning “to tie up”), is also accredited to Indian culture, going back thousands of years. Other techniques like Batik and Ikat were also used with dyed yarn or woven fabrics. India was one of the first places to produce cotton in large quantities, and produced many dyed cotton textiles that were traded in other countries.

This video discusses the complex and problematic history of Indigo dye beyond South Asia (see also North America below for more details about the creation of blue jeans):

Egypt and Persia (North Africa & Middle East)

Ancient Egyptians wore mostly white linen textiles, but they also dyed fabrics in a range of colours. They used Madder for red dye, Safflower for yellow, Indigo or woad for blue, and Murex snails for purple (Tyrian purple was originally made by the Phoenicians).

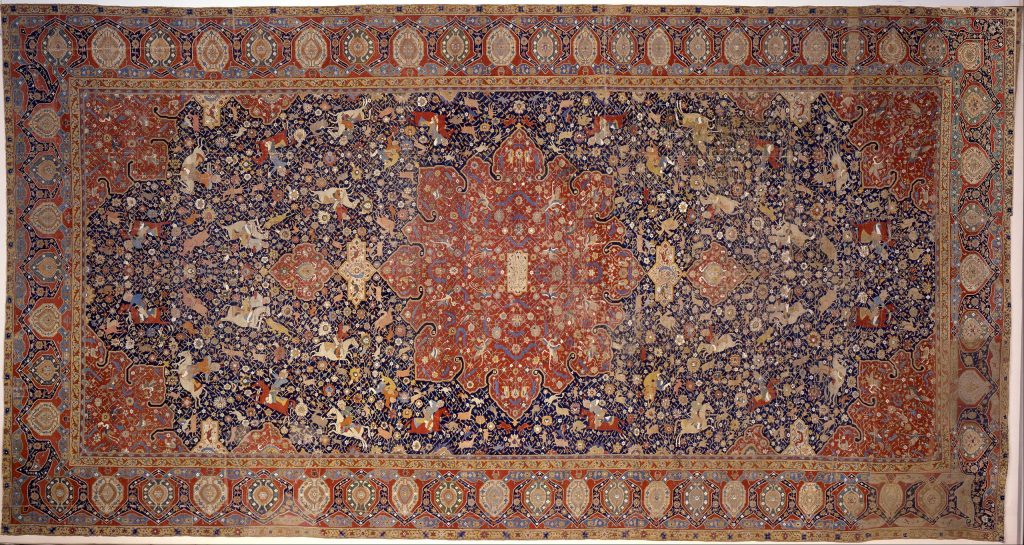

Ancient Persians also developed rich colours using dyes like runas (madder), red grain (kermes or cochineal beetles), walnut, neel (indigo), vine leaves, and other plant materials. Methods for dyeing wool and silk with these diverse colours coincided with the creation of woven and knotted carpets – something we still associate with Persian culture today.

The first carpets date back over two thousand years and were created by nomadic tribes and royal courts. Each group would have their own designs and colours which reflected the history and symbolism that was important to the creators. Carpets created during the Safavid Empire (1501-1736) are world famous for their intricate designs using intense colours, and there are many examples held in museums around the world – here is one example shown in Figure 117.

Google Art Projectでのアーティストの詳細, Ghyas el Din Jami – Tabriz (?) – Google Art Project, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

Watch this video to see the restoration of a Safavidic carpet:

West and South Africa

There are many different types of dyes and textile designs that come from the many countries and regions in Africa. Groups develop their own designs with colours that have symbolic and cultural meanings. Techniques such as batik and tie-dyeing developed in African cultures, and common dyes included indigo, kola nut (brown), annatto (a yellow and orange colour), and earth colours.

Visit this website: The Fabric of Africa , on Google Arts and Culture, to see many beautiful and diverse examples of African textiles from different parts of Africa.

This video shows the work of artisans who practice West African (Nigeria, Ghana and Mali) ancient textile traditions: Adire, Adinkra and Bogolan ‘Mud cloth’. (19 minutes)

Greek, Roman and other Mediterranean civilisations

Ancient Greek, Roman and neighbouring civilisations used a range of plant and animal dyes to create coloured textiles. Plant dyes included crocus sativus (ochres), madder, woad, weld (yellow), walnut hulls, oak gall (brown and black), orchil lichen (pink/purple), alchanet (red), and saffron crocus (yellow).

Animal dyes included kermes beetles (red/cochineal) and seashell creatures such as Hexaplex trunculus, Bolinus brandaris, and Stramonita haemastoma, which created a purple dye similar to the Murex sea snail that was used by the Phoenicians and Romans to create Tyrian purple.[6].

Watch this video for more details about how Tyrian purple was created:

British Isles and North/West Europe

Civilisations from the British Isles and Western Europe used a range of plant materials to create diverse dye colours. Despite being grown across southern Europe and the Caucasus, Britain is primarily known for its woad (Isatis Tinctoria) dye, perhaps because of the legends of Boudicca and the Iceni tribe, who painted their faces with the blue dye. The Celts also used it as body paint and possibly tattoo ink – Romans referred to the Celts as “Picts” (Picti means painted people in Latin) because of their blue tattooed bodies. Evidence of plant materials goes back as far as the Iron Age, and the plant was used for medicinal purposes as well as dye.

Vikings created their own dyes from local plant materials, but they also traded for colours like woad, indigo, madder and cochineal to create more vibrant colours than they could make from local ingredients. They used small amounts of dyes to create decorative edgings on their textiles rather than dyeing entire fabrics. They also used a range of available mordants to fix the dye colour, such as iron, tin, copper, and alum.

Watch this video to learn about traditional dyeing methods, including the use of different mordants that would have been available during the Iron Age (1200 – 550 BCE) in Europe.

North America

Many plants were used by Indigenous Northern Americans to create a wide range of dye colours, such as sumac, bloodroot, alder, cottonwood and black walnut. Early western colonisers noted that native coloured textiles tended to fade quickly, so it is thought that coloured dyes were used in a direct or substantive dyeing method where mordants were not used.[7]

Blue Jeans, Denim and Dungarees

‘Bleu de Gênes’ was made from “bastard indigo”, a plant related to Indigofera, called Amorpha Fruticosa. It was used to produce a blue dye for sail cloth that became known as ‘Bleu de Gênes’ (the blue of Genoa – from Italy), shortened to “jeans“.

‘Tenue de Nîmes’ (Clothes from Nîmes – from France), short name “de Nîmes”, was a textile developed in the 17th century that had a twill weave using one light thread and one dark thread, so the fabric was dark on the outside and light on the inside. The English and Americans eventually turned the name of this textile into what we now know as ‘denim.’[8].

The term “dungarees” most likely comes from a sturdy cotton textile made in Dungri, Gujarat, India, that was often coloured with indigo dye.

Although they originated in Europe and India, these blue textiles are now associated with American culture due to the production of the clothing item we call “blue jeans”. In 1853 a German immigrant, Levi Strauss founded his company in San Francisco, USA, which stocked “denim” fabric. In 1873, Latvian emigrant and tailor Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss patented and manufactured the “XX” pants, which became known as Levi 501s. These are claimed to be the world’s first blue jeans. These jeans had metal rivets on the pockets and a button-fly, which made them tough and suitable as workwear.

Claims that Levis were the first “blue jeans” are disputed by some historians who point to evidence that similar garments were first created by enslaved black people working the indigo and cotton plantations in Southern states. These enslaved plantation workers needed tough working clothes for the hard labour that was part of plantation life. They had ready access to the cotton that came from the plantations to produce the fabric, and they had the cultural knowledge from their African homelands to know how to dye the fabric with indigo – which also had anti-fungal and antibacterial properties.

According to these historians, Davis and Strauss merely added metal rivets to their work pants design and patented the product. [9]

Watch this video for an overview of the origins of blue jeans:

Central and South America

Indigo was used in Central and South American civilisations. There is evidence that it was used in the Andes as far back as 6200 years ago – which predates its use in India, Egypt and other ancient civilisations.[10]

Maya blue was “made by burning incense made from tree resin and using the heat to cook a mixture of indigo plants and a type of clay called palygorskite”. The process of mixing the indigo and tree resin with clay created a long-lasting colour that didn’t fade. In fact, the discovery of artefacts containing this dye has led to physicists developing their own modern version that is resistant to fading and weathering.[11].

Relbun (similar to madder) was used to create red dye over 2000 years ago, but the advent of using cochineal beetles around the 5th Century CE changed dye production in places likes Mexico and Peru. Cochineal became a valuable commodity used for trading and was worth as much as silver to Spanish colonisers. For many years, the Spanish claimed that cochineal was a seed and hid the fact that it was an animal product – to prevent others from breaking their trading monopoly.

Watch this video to learn more about cochineal:

Australia

Australia has Indigenous cultures that have used dyes from a variety of plants, minerals and animal products to colour fibres used for textiles, basket weaving, knotting, and other products for many thousands of years. Different language groups around the continent developed their own knowledge bases using different methods and diverse local materials they found in their geographic locations.

Sally Blake, an Australian artist based in Canberra, studied eucalypts at the Australian National Botanical Gardens, specifically for their dye properties. She has produced an extensive database of Eucalyptus dye colours, which shows the wide range of colours achieved by using the different eucalyptus species, different parts of the plant such as leaves or bark, use of different mordants such as alum, iron or copper, and use with different textiles – wool, silk and linen.

Select the link below to watch this video on YouTube, which shows the bundle dyeing technique using native plants to colour fabric – from Boon Warrung, Wurundjeri and Ngarluma Country. Included are eucalyptus leaves, for yellow, grey or purple colours, eucalyptus bark for purples, and acacia leaves, which can create orange or red colours:

Create unique coloured patterns on fabric using native plants | My Garden Path | Gardening Australia on YouTube

Further resources (RMIT Library search)

Abel, A. 2012, “The history of dyes and pigments: From natural dyes to high performance pigments” Colour Design: Theories and Applications. pp.433-470. 10.1533/9780857095534.3.433. https://rmit.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61RMIT_INST/4t5l5f/cdi_knovel_primary_chapter_kt011G8M02

Samanta, Ashis Kumar, Nasser Awwad, and Hamed Majdooa Algarni. Chemistry and Technology of Natural and Synthetic Dyes and Pigments. Edited by Ashis Kumar Samanta, Nasser Awwad, and Hamed Majdooa Algarni. London: IntechOpen, 2020. https://rmit.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61RMIT_INST/1adn3cm/alma9922172764201341

Delamare, Francois., and Bernard. Guineau. Colour : Making and Using Dyes and Pigments. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000. https://rmit.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61RMIT_INST/1adn3cm/alma9911669840001341, https://rmit.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61RMIT_INST/1adn3cm/alma9911669840001341

Papadakis, Raffaello. Dyes and Pigments : Novel Applications and Waste Treatment. Edited by Raffaello Papadakis. London: IntechOpen, 2021. https://rmit.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61RMIT_INST/1adn3cm/alma9922172633201341

- Sukenik N, Iluz D, Amar Z, Varvak A, Workman V, Shamir O, Ben-Yosef E. "Early evidence (late 2nd millennium BCE) of plant-based dyeing of textiles from Timna, Israe"l PLoS On,. 2017 Jun 28;12(6):e0179014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179014. PMID: 28658314; PMCID: PMC5489155. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5489155/ ↵

- Kvavadze, Eliso, Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. Boaretto, E., Jakeli, N., Matskevich, Z., and Meshveliani. T. 2009. "30,000 Years old wild flax fibers - Testimony for fabricating prehistoric linen", Science 325(5946): 1359. p.2. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4270521 ↵

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. 2023 "Silk Road." Encyclopedia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Silk-Road-trade-route>, accessed 03/01/2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Silk-Road-trade-route ↵

- Han, J. and Quye, A. 2018, "Dyes and Dyeing in the Ming and Qing Dynasties in China: Preliminary Evidence Based on Primary Sources of Documented Recipes". Textile History. 1-27. 10.1080/00404969.2018.1440099. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323917857_Dyes_and_Dyeing_in_the_Ming_and_Qing_Dynasties_in_China_Preliminary_Evidence_Based_on_Primary_Sources_of_Documented_Recipes ↵

- Yoshioka, s. 2010, "History of Japanese Colour: Traditional Natural Dyeing Methods", Colour: Design & Creativity, Society of Dyers and Colourists p. 1, <https://www.aic-color.org/resources/Documents/jaic_v5_gal2nar.pdf>, accessed 04/01/2023, https://www.aic-color.org/resources/Documents/jaic_v5_gal2nar.pdf ↵

- Artextiles.org, 2017, "Dyes", Artext: Hellenic Centre for Research and Conservation of Archeological textiles,<https://artextiles.org/en/content/dyes>, accessed 21/12/2022, https://artextiles.org/en/content/dyes ↵

- U.S. Forest Service, "Native Plant Dyes", U.S. Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, <https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/ethnobotany/dyes.shtml> accessed 02/01/2023, https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/ethnobotany/dyes.shtml ↵

- Stege Bojer, T. 2007, "The History of Indigo Dyeing and How It Changed the World", Medium.com, <https://medium.com/@tsbojer/the-history-of-indigo-dyeing-and-how-it-changed-the-world-35c8bc66f0e9>, accessed 01/01/2023, https://medium.com/@tsbojer/the-history-of-indigo-dyeing-and-how-it-changed-the-world-35c8bc66f0e9 ↵

- Coard, M. 2022, "Enslaved Blacks invented blue jeans", The Philedelphia Tribune, March 1, 2022 <https://www.phillytrib.com/commentary/michaelcoard/enslaved-blacks-invented-blue-jeans/article_57de5262-5b78-534d-a133-bfc406f87a78.html>, accessed 23/12/2022, https://www.phillytrib.com/commentary/michaelcoard/enslaved-blacks-invented-blue-jeans/article_57de5262-5b78-534d-a133-bfc406f87a78.html ↵

- Annalee Newitz - Sep 15, 2016 8:53 pm U.T.C. (2016) World's most valuable dye existed in Peru 1,800 years before anywhere else, Ars Technica. Ars Technica. Available at: https://arstechnica.com/science/2016/09/worlds-most-valuable-dye-existed-in-peru-1800-years-before-anywhere-else/ (Accessed: January 9, 2023). https://arstechnica.com/science/2016/09/worlds-most-valuable-dye-existed-in-peru-1800-years-before-anywhere-else/ ↵

- Powell, D. "Ancient Mayans Inspire Modern Fade Proof Dye", Phys.org, July 30, 2010 <https://phys.org/news/2010-07-ancient-mayans-modern-proof-dye.html> accessed 03/01/2023, https://phys.org/news/2010-07-ancient-mayans-modern-proof-dye.html ↵

The term mordant comes from the Latin mordere, "to bite" because it was thought that a mordant helped the dye bite onto the textile fiber so that it would bind with the fibre and not wash out.

It was called the Silk Road because silk from China travelled westward and was traded for wool, gold and other goods that came from the west and travelled eastward.

A dyestuff is a substance that can be used as a dye or from which a dye can be made. For example, a block of indigo dye can be called a dyestuff, as can a bundle of indigo leaves.

maritime means related to the sea - especially in reference to sea trade or navigation