Middle Ages and Renaissance (c. 400 to 1600 CE)

The Islamic Golden Age: optics and colour systems

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 14th centuries), Arabic Islamic scholars moved away from the theories of Aristotle and Ptolemy to make their own discoveries in colour theory. Between the years 800 – 1200 CE, scholars such as al-Kindi, Ibn al-Haythem (Alhazen) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes), concluded that light was necessary for seeing colours – not rays from the eyes.

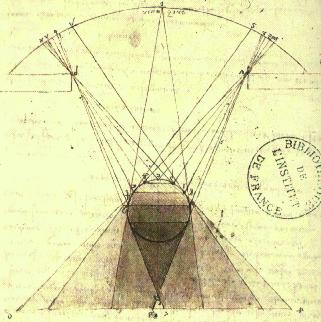

Ibn al-Haythem (known as the father of modern optics – Figure 1.4) experimented with light and glass spheres of water, observing a rainbow spectrum – the bending (refraction) of light rays into different colours. He noted that red light rays bent the least, and blue light rays bent the most. The scholar Nishaburi proposed the beginnings of a hue scale for describing colour in a system.

Ibn al-Haythem, Book of Optics, c. 1011 CE

The Middle Ages: Grosseteste’s colour system

Around 1200 CE, the scholar Robert Grosseteste (Bishop of Lincoln and, it is speculated, the first chancellor of Oxford University – Figure 1.5) developed a colour system of seven colours. Although we don’t know what those colours were, he may have been the first to separate chromatic colours (red, green, blue, yellow) from achromatic colours (black, grey, and white) in a colour system.

The Renaissance: colour primaries and colour wheels

Leon Battista Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci were Italian Renaissance artists and polymaths who both had an interest in colour theory from a practical perspective (circa 1450 to 1500 CE). They wanted to understand colour to better mix pigments for painting artworks. Alberti recognised four colours (yellow, green, blue, red) – although he found yellow to be a problematic colour and sometimes replaced it with grey in his four-colour square. Da Vinci investigated the complexities of colour, light and physical materials such as pigments (Figure 1.6). He listed six colours as his basic primaries (white, yellow, green, blue, red, black). He included green in his primaries although he recognised that green could be mixed from yellow and blue making it also a secondary colour.

Aron Sigfrid Forsius – a Finnish astronomer, documented his theory on the colour values Hue, Saturation and Value in 1611.

The physician and mystic Robert Fludd is credited with developing the first colour wheel based on Aristotle’s theories of colour around 1629 to 1631.

A polymath is a person who has knowledge and experience in a wide range of subjects.

Hue is the term that we use to classify colour. For example if we describe something as "red" or "magenta" or "greenish-yellow", that is the hue. In physics, a specific wavelength of light is a hue. Black, white and grey are not hues, although we may call them colours in a practical sense, for example, when referring to coloured paints or fabrics.

Saturation is the intensity of the colour. Saturated colours appear very vibrant, whereas de-saturated colours tend towards white or grey. A black and white image would have zero colour saturation. Saturation does not relate to how light or dark a colour is.

Colour Value is also known Brightness: this value is different to Lightness – it relates to how bright a colour is, not how light (pale) or dark a colour is.