Colour and language

Naming colours

Research in the field of cognitive science over the last 150 years has included investigations into how language might influence thought and conversely, how thought might influence language. Many of the studies undertaken with different language groups around the world have analysed descriptions of colour as a way of testing these theories.

Some of this research has noted that many language groups have more descriptions for warmer colours (red, orange, purple) and less for cooler colours (blue, green, yellow).

Studies also show that learning a new language alters your perception of colour.

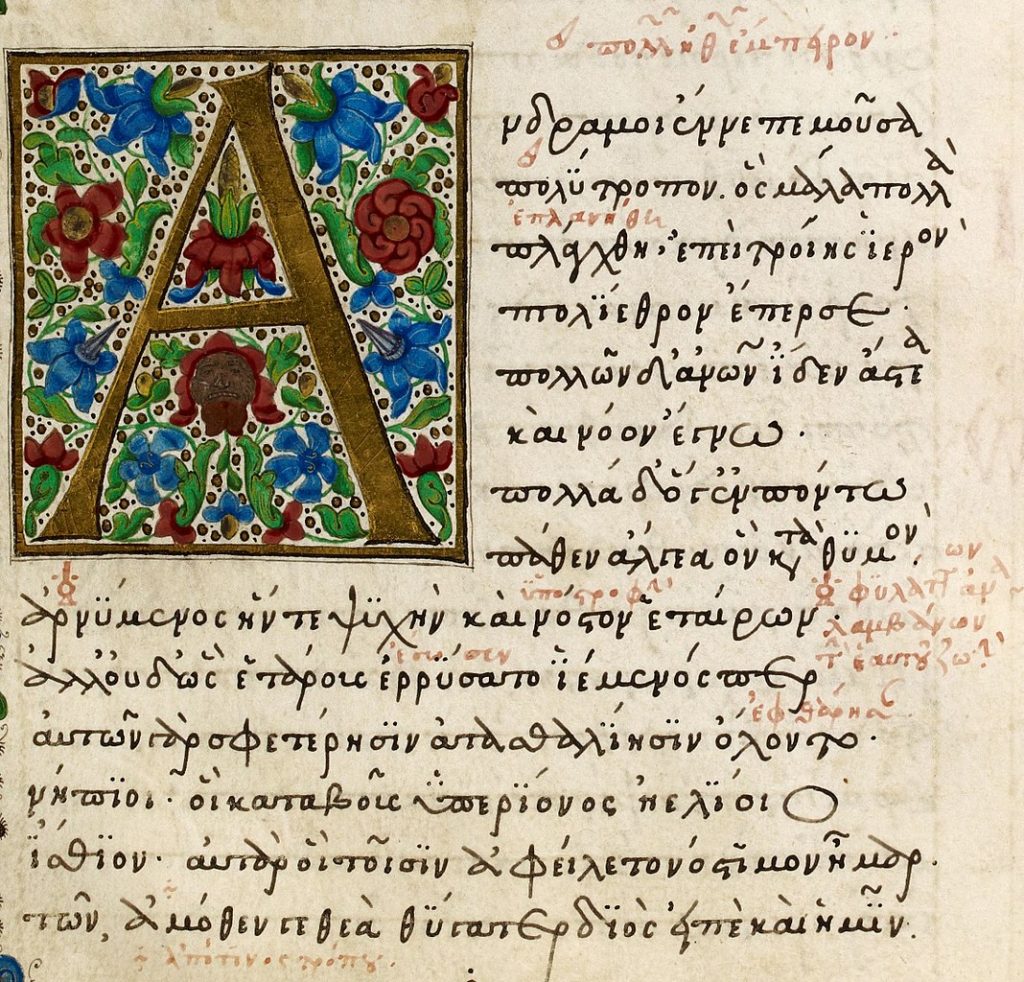

It was speculated that in the past people couldn’t see the colour blue because there weren’t examples of words representing “blue” in ancient texts (Figure 1.34). An example of this proposition was made by politician and historian William Gladstone in his 1858 publication Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age[1] with regard to Homer’s texts The Iliad andThe Odyssey.

However, scientists have concluded that people from ancient times did see blue – they saw the same spectrum of colours that we can see now, but perhaps they didn’t differentiate between blue and green, or used different relational and descriptive words to describe colours like Homer’s “wine-looking sea”. It was an issue of linguistics, not optics[2].

Colour Atlases

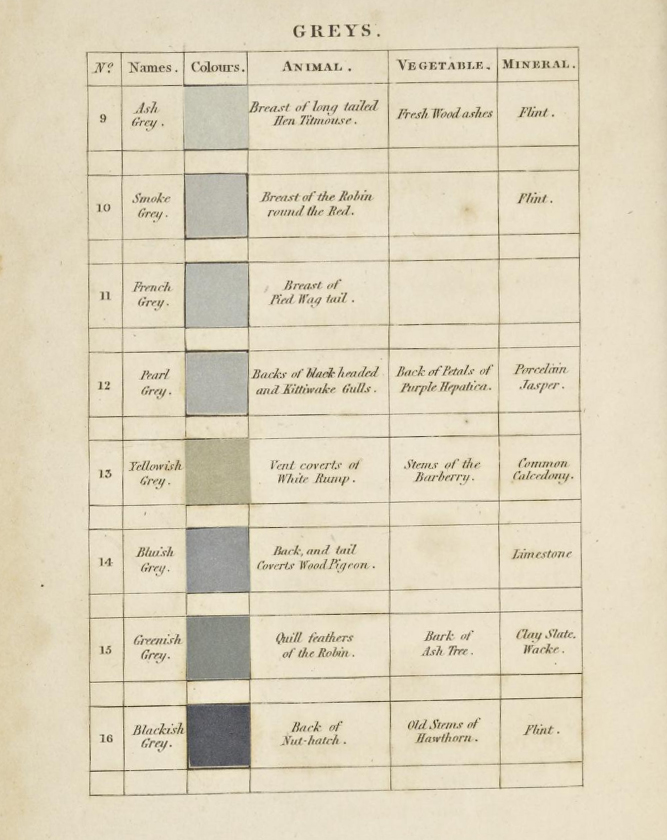

Around the time of Charles Darwin, descriptive language standards – also called taxonomies – for colour used by naturalists were published as ‘colour-atlases’[3] which described colours by hue and value based on natural objects such as plants, animals, and landscape features, not ‘spectral colours’ (colours such as red, blue, yellow, violet, green or orange).

Darwin was said to have a copy of such an atlas – Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Minerology, Anatomy and the Arts by Patrick Syme, 1821)(Figure 1.35), during his voyage on the Beagle[4] (1831-1836). This colour atlas book is still in print today.

This method of colour classification using language standards came about because of the problem of making spectral colours with pigments and dyes at that time. See Chapter 3.4 Colour systems: paints and pigments for more information on pigments and dyes.

The way you think about colour may depend on your language even if we see the same spectrum of colours. Naming conventions in our language for colours may also influence how we think about colour.

Today, we have seemingly endless and non-standard ways of naming colours – some of them are strange or even humorous like these AI-generated colour names. Paint colour charts are good examples of this and they are easy to find online or in hardware stores. Descriptive language is used to classify, differentiate and market thousands of colours that have very slight variations between them.

What’s the difference between “Natural white” and ‘Antique white”?

Learn more from these resources:

Colour idioms in English

What is an idiom? How do we use colour expressively in the English language?

Seeing Red

The phrase “seeing red” now has its own meaning in the English language. It might not have the same meaning in other languages (although some colour idioms can be similar across languages).

English has lots of colour-related idioms. Some relate to emotions and moods, but others are more descriptive.

Green fingers

Read this article for some common examples of colour idioms in English:

- Gladstone, W. 1858, Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47356/47356-h/47356-h.htm ↵

- Bellos, Alex, 2010, "Through the Language Glass: How Words Colour Your World by Guy Deutscher", The Guardian, 12/06/2010, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/jun/12/language-glass-colour-guy-deutscher ↵

- (Gage, J. Colour and Meaning, Thames and Hudson, 2002, p.26 ↵

- Darwin, Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, 1839, http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?pageseq=2&itemID=F10.3&viewtype=side ↵

Cognitive science is the study of how the mind works, functions, and behaves. It includes aspects of psychology, linguistics, philosophy, neuroscience and artificial intelligence.