Colour dyes: synthetic colours and sustainability

Impact of synthetic colour development

Egyptian blue[1] was one of the first synthetically created pigments, made from crushed blue glass (silica and copper) over two thousand years ago. Although synthetic pigments and dyes have existed throughout history, it wasn’t until the industrial era that there was a boom in chemical synthetic colours that were relatively cheap and easy to make and therefore used in industry for the mass production of paints and dyes, which were used in products like textiles, paper, plastics, and many other materials.

Prussian blue was the first chemical synthetic colour accidentally created by Johann Jacob Diesbach in 1704. One of the first synthetic dyes to be mass-produced was a mauve colour called Mauveine (also known as Aniline purple and Perkin’s mauve). It was also accidentally discovered by William Henry Perkin in 1856 while he was trying to create the chemical quinine, which was used at that time for the treatment of malaria.

Mauvine

#8D029B

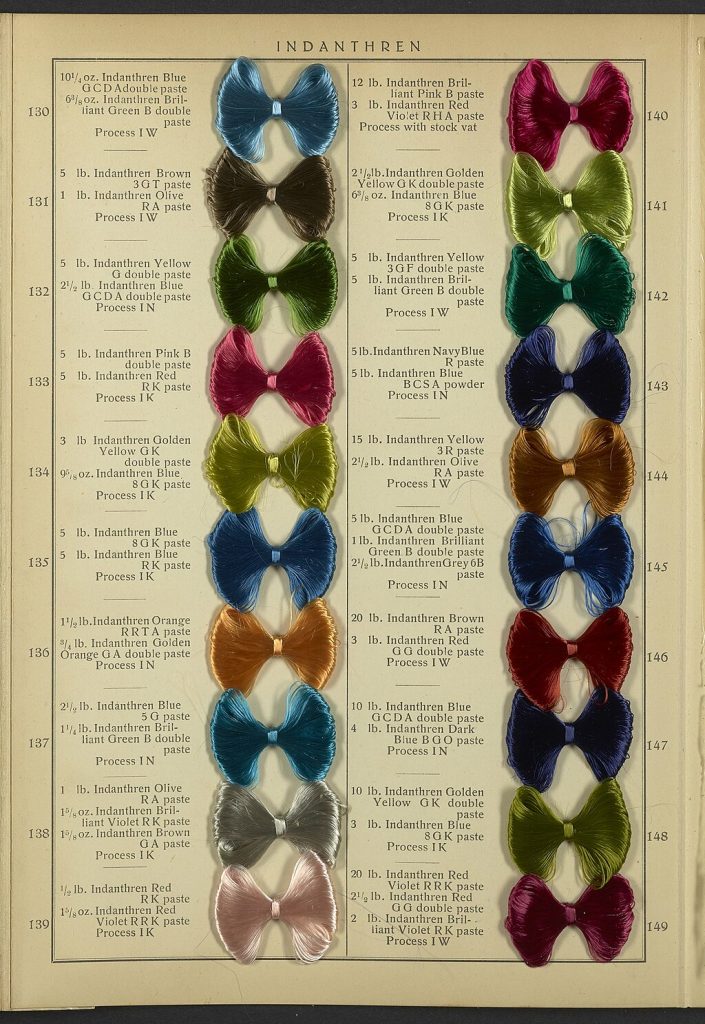

Many of the synthetic colours we now use in artist paints and industrial practices (Figure 3.45) are safer and cheaper options than the equivalent pigments from the past. Older colours like realgar, vermilion and emerald green are highly toxic due to their chemical compounds which include lead, mercury, arsenic or other dangerous materials that are harmful to human health. Many people became ill or died from the creation and use of pigments and dyes containing these toxic substances. Learn more about this in Special colours, controversial colours and interesting facts on the next page.

by Science History Institute via Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain.

Hair dyes

People have been dyeing their hair for thousands of years too! Ancient cultures used natural dyes like Henna, Indigo, Tumeric, Senna, Walnut and Cochineal to dye their hair a range of colours, such as red, orange, yellow, black, brown, or even green. Some ancient people like the Celts also bleached their hair with lime or other substances that would strip the hair of colour.

Natural dyes can create unpredictable results because they may have different amounts of reactive substances and colourants, and they also tend to fade over time. Some products, like “black henna” (which is not actually henna), can cause extremely serious allergic reactions and are banned in many countries.

Synthetic hair dyes were first developed in the late 19th century. French company L’Oréal was the first company to manufacture synthetic hair dyes around 1907, and the German company Schwarzkopf was the first to create at-home hair dyes in 1947. Today, hair dye products are a huge industry and are available in a wide range of colours – in fact, all the colours of the spectrum (Figure 3.46), as well as natural colours and treatments that bleach or lighten the hair.

There are temporary and permanent dyes that can be used to colour hair (including facial hair). However, some colours are more lightfast than others, and even colours classed as “permanent” can still wash out or fade – especially colours like violets, blues and greens, which are more fugitive dye colours. You can also now get hair dyes that fluoresce in UV light – known as blacklight-reactive hair dyes.

Sustainability, waste and pollution from making and using dyes

Dye production and usage (both natural and synthetic dye) has had a problematic history due to the use of petrochemicals to create synthetic colours, the use of water in the dyeing process, and the creation of wastewater from the washing process.

Since the advent of industrial and synthetic dye-making processes (Figure 3.47), and industrial use of dyes for producing textiles and other materials, industries working with dyes have caused a lot of pollution and used great quantities of clean water.

New methods are being developed that seek to reduce waste in dye production and usage, to create a more sustainable industry. This also impacts broader issues in the fashion industry relating to clothes wastage and sustainability.

These articles have more information on this topic:

- Pailliè-Jiménez M E, Stincone P, Brandelli A 2020, “Natural Pigments of Microbial Origin”, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, Vol 4, 2020, viewed 07/12/2022, <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.590439>, DOI=10.3389/fsufs.2020.590439, accessed December 21, 2022

- Bealle, A. (2020) Why clothes are so hard to recycle, BBC Future. BBC. <https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200710-why-clothes-are-so-hard-to-recycle>, accessed: January 3, 2023

- Lellis, B. Zani Fávaro-Polonio, C. Alencar Pamphile, J. Cesar Polonio, J, 2019, “Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms”, Biotechnology Research and Innovation, Vol 3, Issue 2, 2019, Pages 275-290,

ISSN 2452-0721, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biori.2019.09.001.<>, accessed 04/01/2023

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain.

- Pradell, T., Salvado, N., Hatton,G.D., Tite, M.S., 2006, "Physical Processes Involved in Production of the Ancient Pigment, Egyptian Blue", Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Volume89, Issue4, April 2006, pp. 1426-1431, https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2005.00904.x, https://ceramics.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2005.00904.x ↵