Colour symbolism in different cultures

Symbolic colour meanings have been associated in art and anthropology with different cultural, spiritual or religious groups throughout our recorded history. In many ancient cultures, colour symbolism was related to the natural elements – earth, water, fire, air, etc.

For example, traditional Chinese colour symbolism associates the elements and primary colours shown in Table 1.2.

| Colour sample | Definition |

| Red (Zhusha Hong) = fire | |

| Yellow (Ming Huang) = earth | |

| White (Chun Bai) = metal | |

| Black (Xuan Se) = water | |

| Blue (Qing Se) = wood |

In other cultures, certain colours that were made from rare pigments were highly prized and thus came to have symbolic meaning. Here are two examples:

Tyrian purple

In ancient Roman culture, purple (Tyrian purple or Phoenecian red/purple) was a special colour reserved for the clothing of emperors and senators. This was because the vibrant purple dye was made from a particular species of sea snail (Murex or Muricidae) and it was expensive and very difficult to create.

Deep red porphyry from Egypt (Imperial Porphyry) is an igneous rock that was also valued by the Romans because it was very close to Tyrian purple in colour. Figure 1.25, shows a statue of Minerva (as Goddess Roma) from Capitol Square in Rome (c 300 CE). Her dress is made from red porphyry to represent the Tyrian purple dye of imperial Roman clothing. (Read more about dyes in 3.4 Colour systems: pigments and dyes)

Ultramarine (lapis lazuli)

Blue was used symbolically in Christian religious imagery during the Renaissance – partly because the blue pigment was very rare. The cloak of the Virgin Mary was often coloured with ultramarine blue (Figure 1.26). The colour blue also represented the heavens and the celestial, so it had more than one symbolic meaning in this context.

Ultramarine pigment was made from a deep blue precious stone –lapis lazuli, said to be worth more than gold at the time. It has been claimed that Michelangelo couldn’t afford enough ultramarine blue for the Virgin’s cloak, and so never completed his painting The Entombment.

Johannes Vermeer put his family in debt to acquire the pigment for his paintings such as The Milk Maid (Figure 1.27).

Flags of the world

In contemporary international culture, we see symbolic colour all around us in fashion, products and media. Flags of the world are also an obvious example of symbolic colour (Figure 1.28). Colours used in national flags have symbolic meanings related to a country’s culture and history.

Australian First Nation flags

Our Australian Aboriginal flag (Figure 1.29) has three colours in a design that represents:

- the earth (red),

- the people (black), and

- the sun (yellow)

The Torres Strait flag has the following colour symbolism:

- Green – the mainlands (Papua New Guinea and Australia)

- Black – the people of the Torres Strait Islands

- Blue – the waters surrounding the islands

- White Dhari – the Dhari is a traditional headdress made and worn by men. The white colour symbolises peace.

- White Five-Pointed Star – the five major island groups and their ties to navigation by sea

View the Torres Strait Flag here (copyright permission to reproduce the flag must be obtained from the TSIRC).

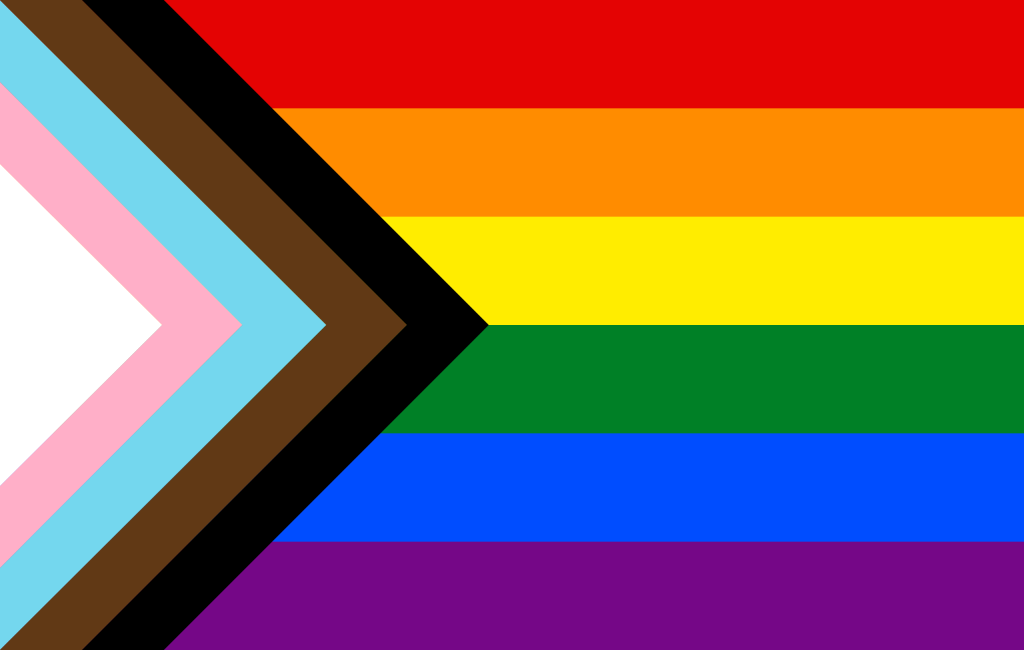

Pride flags

Pride flags of the LGBTIQA+ community use colours symbolically to represent various groups. There is one overarching rainbow flag for the whole community (Figure 1.30) (and a Progress Pride flag – Figure 1.31), but each subgroup also has their own flag with symbolic use of colour.

Learn more about Pride flags and colour symbolism from these online resources:

- Pride flag on Wikipedia

- Understanding color psychology though culture, symbolism, and emotion

- Color symbolism on Wikipedia

- Cross-cultural color and emotion

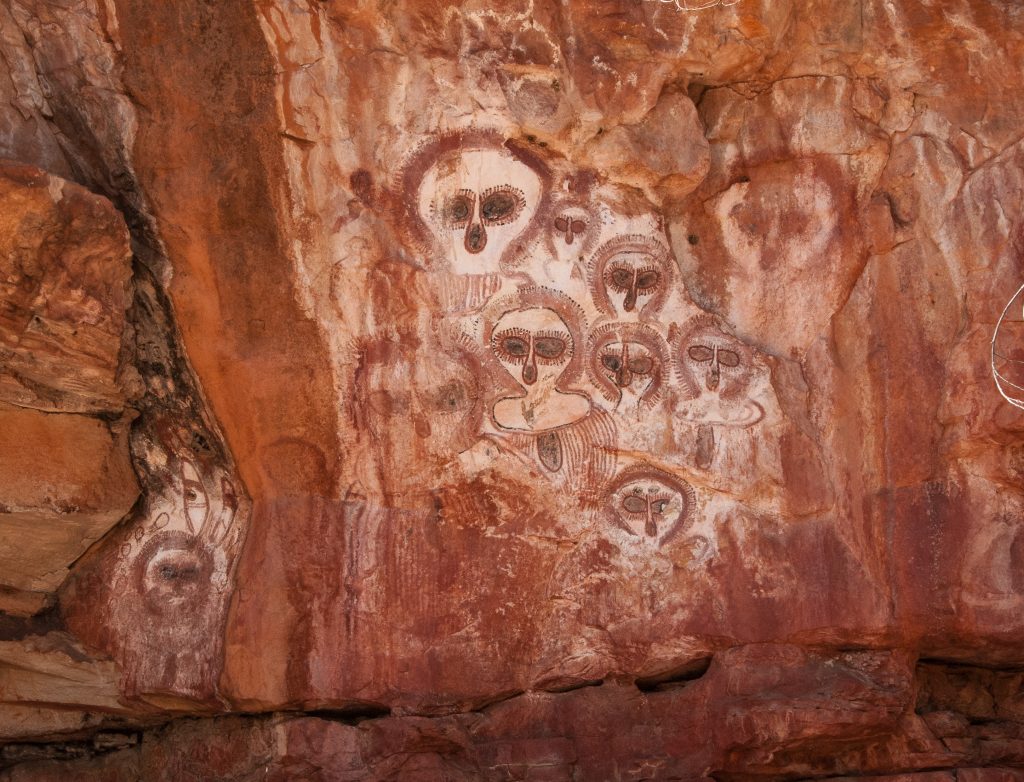

Colour symbolism in Australian Indigenous culture

Traditional Australian Aboriginal artists used the materials at hand – ochres from the ground (Figure 1.32), plants and other substances used to make dyes. Different language groups across the continent developed their own symbolic uses for colour to represent the earth, sky, animals, people, waters etc. There isn’t one set of meanings that covers the whole country, and some meanings and colour making methods may be protected knowledge of certain groups.

Since European colonisation, many Indigenous artists have embraced a wider range of colours in their work – partly due to the availability of ready-made paints, or the use of digital media. In particular, since the 1970s and the beginnings of painting movements by groups in central and western Australia, materials like acrylic paints have become popular because they are available in a variety of colours, are easy to use and quick to dry. Brighter colours have been incorporated into many Indigenous artists’ practices (Figure 1.33). These colours are symbolically used to represent the intensely coloured and vibrant features of diverse landscapes across the country. Learn more about pigments and dyes in Chapter 3 – Colour systems: paint pigments and dyes

Learn more about colour in indigenous culture from these resources:

- Aboriginal Art Australia: The story of Aboriginal art

- Japingka Aboriginal Art: How Aboriginal colours and group art styles develop

- Kate Owen Gallery: Aboriginal-colours-in-art

- RMIT News: Louisa Bloomer tree artwork

- RMIT News: Mark Cleaver, Indigenous artwork Luwaytini

Anthropology is the scientific study of human behaviour, biology, societies, cultures and languages.