How the brain interprets colour information

Binocular vision

As stated in the Optics section on 3D glasses, we have two eyes, yet only see one image. The brain processes a lot of visual information that comes from two sources at the same time, and it puts this all together to make one image that allows us to interact with the world around us. There are many complex processes happening very quickly, all at once. It is thought that around 40% of the brain’s function is used for processing vision.

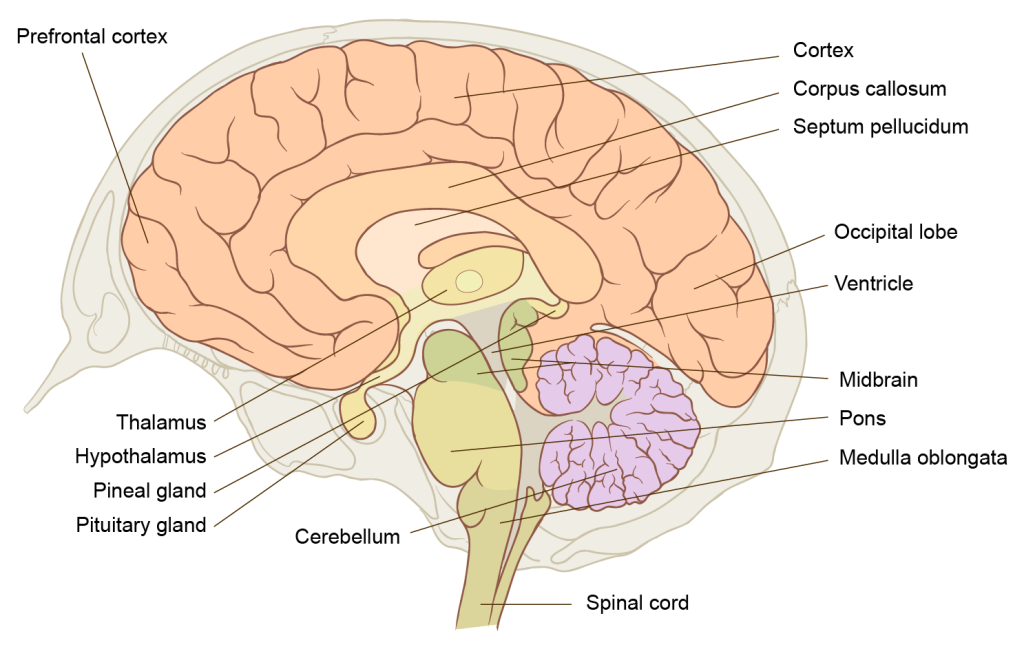

The optic nerve connects the retina at the back of the eye to a part of the brain called the thalamus (Figure 2.49). The thalamus processes the information from both eyes and sends it to another part of the brain – the visual cortex in the occipital lobe. The visual cortex contains cells that detect different kinds of visual information, like colour, form and movement. It puts all of this information together into what we perceive as an image. This image is then sent to the prefrontal cortex, which processes that information along with other information, like emotions and memories. This all helps us to not only see but to understand what we are seeing and make sense of objects, movement, depth perception, light and colour.

Watch this video for more information

The way we perceive colour is subjective and can depend on how we are seeing the environment, the lighting, and the positioning of colours next to each other. This relates to the content in chapter 1, section 1.3 colour aesthetics, and the creative experiments done by artists and theorists like Johannes Itten and Josef Albers.

Read this article: Colour is all in our heads!

Is Magenta a real colour?

There was a recent online article claiming that magenta isn’t a real colour because it doesn’t exist on the colour spectrum. Of course, you could say that about any colour that isn’t visible on the spectrum as a single wavelength (like brown, for example) because our brains interpret many light wavelengths from the visible spectrum and mix the wavelengths for red and blue to make a colour that we see as magenta.

Read this Ars Technica article to understand the whole story.

Optical illusions

Optical illusions can tell us a lot about how our brains make sense of the light waves that enter our eyes. One of the most common illusions relates to relative colour and lightness. A colour can look completely different depending on what’s next to it.

The animation in Figure 2.50 is a good example of the concept. The moving square does not change colour at all, but our perception of the colour changes as the background colour blends from pink to green.

It also helps explains recent viral social media phenomena like the striped dress – is it blue and black or white and gold?

Learn more about optical illusions here and watch this video for more information.

This video discusses how what we see is subjective – can you really trust what you see?