Problematic colours

Some pigments and dyes have a problematic history due to how they were created and used, which was harmful to humans or animals, or because they contain toxic substances that poisoned people who were working with them, causing serious health problems and death.

The Library of Rare Colours

View this video to learn about a rare collection of pigments (including some problematic ones): the Forbes Pigment Collection at Harvard Art Museums in the USA (5 minutes)

Media attribution: The library of rare colours by Tom Scott on YouTube

Problematic and dangerous colours

Read on to learn about some problematic pigments and their stories…

Mummy brown

Also called Mumia or Caput Mortuum (Latin meaning dead head), Mummy brown was a rich brown pigment made from grinding up real mummified humans and animals. Eventually, the supply of mummified bodies declined, and people began realising how the pigment was made and found it distasteful, so it was no longer produced or used. The modern artists’ pigment called Mummy brown is made from inorganic earthy substances.

Note: There is another colour known as Caput Mortuum Violet, which has a more purplish, mauve-brown colour, like dried blood. It was made from iron oxide and used by the Romans.

Read more about Mummy brown in this Harvard Museum article

Indian yellow

Indian yellow has a controversial history. It was claimed that the pigment was produced from the urine of cows that were fed only mango leaves, but this story was disputed by some sources. The story claims that cows were malnourished and sickly as a result of the diet and that this practice was outlawed in 1908 due to animal cruelty. Investigations into this story revealed no evidence to support it. However, more recent chemical analyses of pigment samples from the past, going back to 1400 CE, have shown that in some cases, the origin of this pigment was from cow’s urine, so historically, the pigment was produced this way. Today Indian yellow (Figure 3.56) is made by synthetically producing euxanthic acid – which is the main component.

Learn more about Indian yellow

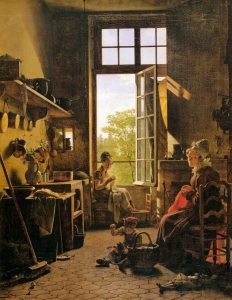

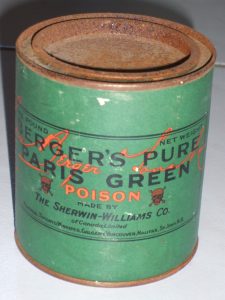

Scheeler’s green and emerald green (also known as Paris green – Figure 3.57)

These pigments are very toxic due to the main ingredient, which is arsenic. This type of green paint and dye became popular as wallpaper and as a textile colour for women’s dresses and accessories in the Victorian era. It soon became clear that emerald green fabric and furnishings caused terrible health problems associated with arsenic poisoning, such as skin blisters and sores, nausea and vomiting, and death. Despite this, many still wore the colour, as it was so fashionable at the time.

Emerald green was also a popular artist-quality pigment used by Van Gogh, Cezanne and other Post-Impressionists around the late 1800s. After its toxic effects were discovered, the pigment was no longer used for making textiles and furnishings. However, it continued to be used as rat poison.

Learn more about dangerous fashion from this book: Matthews David, Alison. Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present. London: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2017

White Lead (or lead white)

This was a common pigment made from lead carbonate, and its use dates back at least as far as 300 BCE. It was created using what was called “the Dutch method”, where lead was exposed to vinegar for long periods of time, which would corrode the lead and turn it white (the smell was supposed to be terrible). This white substance would then be scraped off and ground into a powder. It was highly toxic because of the lead content.

White lead (Figure 3.58) was popular as an artist’s oil paint due to its opacity and smooth texture. It was also used in cosmetics as a face paint or powder. Both uses were dangerous, causing health issues and death for those who had ongoing contact with the pigment. Perhaps because of its toxicity, it was used in the 18th century to paint wooden ship hulls and floors because it helped to prevent infestation by shipworm – a pest that would eat the ship’s timber. Lead white pigment is now banned in most countries, although an artist’s material known as Flake white or Cremnitz white does still exist and can be purchased in some formats. Some artists still prefer lead white to zinc white or titanium white because it’s more translucent, not as flat, and mixes well with other coloured pigments. A lead-free flake white is now also available that contains a mixture of other kinds of white pigments.

Vermilion/cinnabar

Also known as Sindoor, vermilion is a bright red pigment that is highly toxic because of its mercury content (mercury sulphide is its main element). Vermilion made from cinnabar was used across many cultures since prehistoric times in paintings and objects. It is well known as Chinese Red for the red lacquer paint applied to furniture and objects. It was a very popular artist’s pigment during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, although it was very expensive. It has also been used in cosmetics since ancient times, across Asia, Europe and the Middle East in products like lipstick and cheek rouge because of its vibrant red colour. Mining, working with, and wearing the pigment caused mercury poisoning.

As an artist’s pigment, it wasn’t very lightfast, so was prone to fading over time (see Figure 3.59). Today, it has been replaced by Cadmium red as a safer and more stable option.

Read this article on How Stuff Works to learn more about cinnabar toxicity.

Cochineal

This is a scarlet-red dye or pigment made from cochineal beetles (Figure 3.60). While not toxic or unethically produced like the other pigments listed here (unless you are vegan), the failed attempt to create a cochineal industry in Australia in the late 1700s led to the imported prickly pear plant Opuntia running wild and becoming a restricted and prohibited weed (it was brought to Australia as a food source for the beetles).

Eventually, in the early 1900s, another insect, the cactoblastis moth, was brought to Australia as part of a prickly pear reduction program. These moth larvae were very successful in destroying the plant, which had an enormous impact on the land and enabled settlement of areas previously infested with prickly pear. It is still regarded as one of the most successful weed eradication programs using biological means instead of harmful chemicals. Learn more about the prickly pear story here .

There is some controversy over the use of cochineal as a food colouring, which, if not specifically disclosed, is a problem for vegans, vegetarians, Muslims and other people who choose not to eat insect-based products.

Indigo

Indigo is not a toxic dye, but indigo plantations have an unethical historical association with the African slave trade in North America and elsewhere around the world. Many people were forced to work in indigo plantations under terrible conditions with cruel mistreatment by plantation owners and managers. Other crops like cotton, tobacco, sugar and coffee have similar histories.

The development of synthetic indigo meant the end of indigo plantations. However, there is a return to more sustainable and environmentally friendly methods of dye production that don’t use petrochemicals. Natural indigo (Figure 3.61) may yet have a resurgence in popularity, although with more ethical and sustainable production processes.

Learn more about the history of indigo in this article: The Dark History of Indigo, Slavery’s Other Cash Crop by Jesslyn Shields, HowStuffWorks.com, Feb 7, 2020

Luminous radium paint

Known as the Radium Girls, many girls and women in the early 20th century were poisoned by working with luminous paint that contained radium (which glowed in the dark), to create watch, clock and instrumentation dials (Figure 3.62). The women engaged in this factory work were encouraged to lick the tips of their brushes to create a fine point, thereby ingesting the radium, which caused terrible health conditions, including dental problems, fertility problems, necrosis of the jaw, anaemia and cancer.

Further reading

You can find more information about the topics on this page by reading:

or visit this website: Pigments Through the Ages.