Additive and subtractive colour systems

Additive Colour

Additive colour works by mixing colours of light. The more colours of light you add together, the closer you get to white light. It is the opposite of the colour spectrum, where white light is refracted (broken up) into a rainbow of colours.

Additive primary colours are Red, Green and Blue (RGB). These are the colours from which all other colours of light are made. You can see evidence of this on your computers, televisions and mobile phones. Pixels emit light in different colours based on how much of each primary colour is emitted from each pixel (RGB values).

More about additive colour can be found in this resource: 3.2 Colour systems: digital.

Subtractive Colour

Subtractive colour involves mixing physical materials like paint pigments, printing inks, and dyes. The more colour materials you mix, the darker the colour gets. It’s called ‘subtractive’ because of the absorption or subtraction of certain wavelengths from white light. This absorption is based on how different atoms behave when light hits them. See Chapter 2. Colour theory: the visible spectrum in this resource for more information about the physics and chemistry of colour.

Subtractive primary colours are Cyan, Magenta and Yellow (CMY). The traditional primaries Red, Yellow and Blue (RYB) are also useful to know about in some contexts, like understanding the historical development of colour theory and using older colour wheels. Psychological primaries Red, Yellow, Green and Blue are colours that were once also defined as primary because of historical colour theories about how our eyes perceive colour. See Biology of the human eye for more information about human colour vision and subtractive colour.

A simple example to explain how subtractive colour works

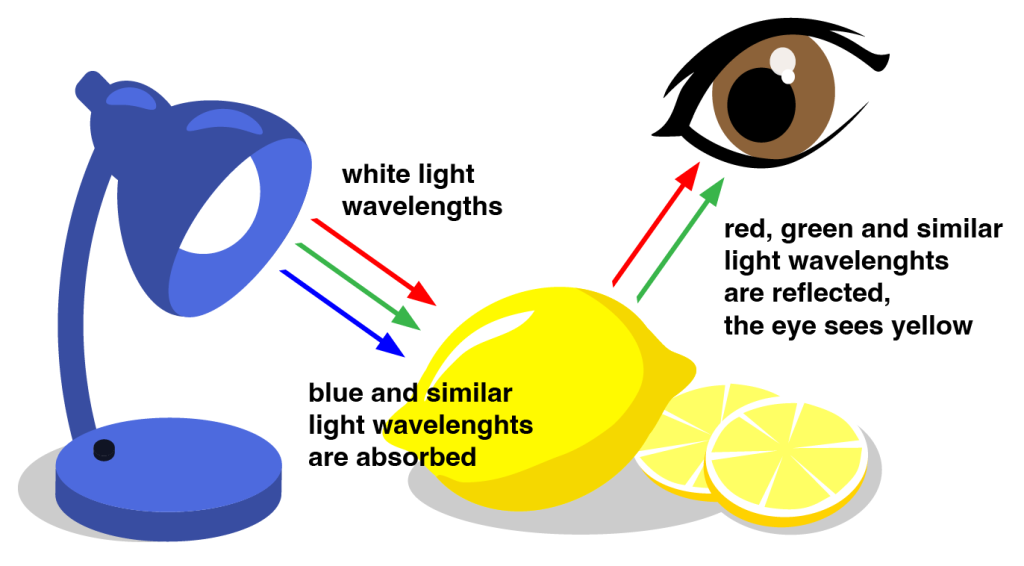

Observe something yellow, like a bowl of lemons with white light shining on it (Figure 3.5). The lemons are reflecting light wavelengths that we perceive as yellow and absorbing all other light wavelengths. We see a yellow colour because its opposite colour – blue (and other similar light wavelengths) is subtracted from the white light. Red and green light when mixed create yellow, so certain amounts of red and green light wavelengths (and other wavelengths between red and green) bounce off the lemons and our eyes see those light wavelengths as yellow.

by RMIT, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 using images by OpenClipart-Vectors and Simona via Pixabay, CC0.

Note: for printing, we use the CMYK colour system. In this system, K represents blacK. Black is used as an extra colour when printing because conventional CMY printer inks don’t blend well enough to create a good black colour. Also, black ink tends to be much cheaper than coloured inks.

More detailed information about subtractive colour can be found in 3.3 Colour systems: printing and 3.4 Colour systems: paint pigments and dyes.